Art Essay: The Child Within – Part 2

By Ina Cole

ART TIMES Spring 2014

Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky in their garden in Dessau (c 1927) Picture: Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau, Munich |

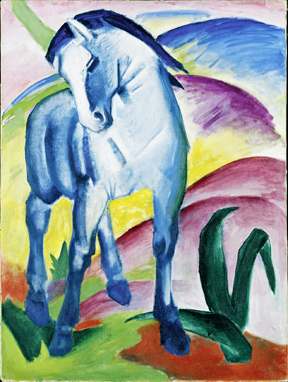

As artists in the early twentieth-century began to explore increasingly diverse means of expression, untainted by the corruption and materialism of their age, a distinct yet wholly international group emerged. The Blue Rider was formed in Munich in 1911 as an association of painters led by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, with Alexej Jawlensky, Paul Klee, August Macke and Gabriele Münter amongst its key members. The name, Blue Rider, refers to motifs utilised in the work of both Kandinsky and Marc, as well as to a book the two artists had previously published. The group had a commitment to a form of abstraction that was organic in its creative process; in simplification or reduction to essentials, the play of volume against flatness, and the creation of a wealth of forms that stood parallel to the infinite variety in nature. The Blue Rider differed from other groups at the time in that it was openly receptive, promoting cross-fertilisation between the arts and including musical analysis and theory in an almanac, as well as art from different cultures and periods, from cave art onwards. The aim for collecting images for the almanac was that they should have been formed through an inner necessity, and this criterion was applied to primitive artefacts and children’s art, which were both articulated along the same theoretical lines.

A few years earlier, in 1905, several major studies had been undertaken in Germany on the nature of children’s art and its stages of development. Munich became one of the principal centres for these studies, largely due to the work of Georg Kerschensteiner, superintendent of public instruction in Munich, whose comprehensive investigation of the subject was published that year. The crudities of children’s art offered artists the opportunity for personal expression undiluted by conventional forms or the need to render appearances faithfully. This was important in that it signified a shift from academic convention at a time when scholarly interest in children’s art was at its height. In particular, Klee’s interest in untutored forms of art contributed to what he called his ‘primitive realm of psychic improvisation’ (Franciscono 1991). However, it took until 1911-12 before he was able to successfully incorporate these elements into more abstract configurations, through his encounter with The Blue Rider and their shared interest in the work of children. Certainly Münter and Kandinsky’s immense collection of children’s art did much to reconfirm Klee’s own interest in the subject. The notable features of this collection was the liberated and unconventional spatial organization in the works, and the way in which feelings were given a visible existence, becoming documents of a universal humanity, not unlike tribal art which also expresses a collective rather than an individual sentiment.

Franz Marc, Blue Horse 1 (1911) Picture credit: Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau, Munich |

The Blue Rider felt that they needed theoretical support for their ideas and seized upon Wilhelm Worringer’s Abstraction and Empathy, first published in 1908. In this seminal work Worringer explains the great visual differences between works of art separated by time and culture, in terms of their relative position between two opposing creative urges, which he described as the need for empathy and the urge to abstraction. The abstract mode of portraying the object with just a few structural features is prominent in the early stages of development and in the work of primitive cultures, resulting in an elaborate play of geometric, ornamental, formalistic, stylized, schematic and symbolic shapes. He claimed that abstraction therefore exists at the beginning of every primitive epoch of art; in European tradition it makes way for the urge to empathy, yet it remains largely unchanged in the work of the primitives, where vision is seen to penetrate behind appearances. On the psychic presuppositions for the urge to abstraction Worringer writes, ‘We must seek them in these peoples’ feeling about the world, in their psychic attitude towards the cosmos. Whereas the precondition for the urge to empathy is a happy pantheistic relationship of confidence between man and the phenomena of the external world, the urge to abstraction is the outcome of a great inner unrest inspired by man by the phenomena of the outside world’. He goes on to say, ‘The style most perfect in its regularity, the style of the highest abstraction, most strict in its exclusion of life, is peculiar to the peoples at their most primitive cultural level’ (Worringer 1982).

A connection therefore has to exist between primitive cultures and the highest, purest regular art form. This does not mean that the primitive actively looked for regularity in nature, rather it was due to a feeling of being lost in the universe that a need emerged to free the objects of the external world of their obscurity and give them an understanding, much in the way a child would. This approach is instinctive and it is because intellect has not yet dimmed instinct that the inclination towards regular forms was able to find the appropriate abstract expression. The conditions that led to the creative output of primitive cultures appeared to many of Worringer’s readers, such as The Blue Rider, to parallel those under which they themselves labored, and the appeal of his ideas lay in the ease in which they could be reapplied to developments in modern art. This theory was also applied to children who, impervious to component detail, perceive reality as an undifferentiated whole; their spontaneous works often valued for their supposed formal-abstract qualities. Indeed, in a review of the first Blue Rider exhibition Klee wrote, ‘For there are still primal beginnings in art, which one is more likely to find in ethnographic museums or at home in the nursery...children can do it too…there is positive wisdom in this state of affairs. The more helpless these children are, the more instructive is the art they offer us’ (Franciscono 1991).

The Blue Rider survived only three years, but its impact on the development of modern art remains an enduring topic of discussion. The group was largely

dissolved by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, with both Marc

and Macke killed in combat.Kandinsky and Jawlensky were forced to

move back to Russia due to their Russian citizenship, and Münter’s relationship with Kandinsky came to an end. Klee progressed to develop a highly

individual stance, continuing to incorporate childlike elements in his work, albeit within increasingly theoretical structures. This was of course one of

several preoccupations in a complex artistic career, but an important one that yields a remarkable clear glimpse of his creative process. Indeed, it was

through his acute observation of human physiognomy and attention to the smallest manifestation of form and interrelationship that he was able to comment on

the magnitude of natural order. Klee’s continued use of childlike images acted as a pivot to a way of seeing that is opposed to adult perception, which

orders the world in utilitarian terms as a set of causes or means. In this sense, the child within is only a child buried by the conventions of human

socialization, difficult to reach, yet continuing to exercise potent influences on the entire range of the adults’ behavior.

(Kandinsky in Paris, Guggenheim Museum, New York to 23 April 2014; The Journey to Tunisia: Klee, Macke, Moilliet, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern until 22 June

2014; Kandinsky: A Retrospective, Milwaukee Art Museum from 5 June – 1 September 2014; German Expressionism: A Revolutionary Spirit, Baltimore Museum

of Art, Maryland to 14 September 2014; August Macke and Franz Marc: An Artists’ Friendship, Lenbachhaus, Munich from 24 January 2015 to 3 May 2015;

Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky: An Artists’ Friendship, Lenbachhaus, Munich from 24 October 2015 – 24 January 2016)