(845) 246-6944 · info@ArtTimesJournal.com

Prints

vs. Reproductions

By PHIL

METZGER

ART TIMES Jan/Feb, 2005

Question:

When is a print not a print?

Answer: When it’s a reproduction.

|

|

Like a lot

of words in the English language, “print” and “reproduction”

are often misused, sometimes by accident, sometimes on purpose. Both prints

and reproductions are copies of some original image, but they are

made in quite different ways. Prints are copies painstakingly made by

the artist, one at a time; reproductions are copies made mechanically,

usually quickly and in large numbers, without involving the artist. Because

the term “print” has been watered down and made ambiguous,

some prefer the term original print to more firmly signal the participation

of the artist in its production.

Prints

are made in a number of ways: Relief prints (e.g., woodcuts, linocuts)

are made by carving away unneeded areas from the surface of a material,

inking the remaining areas and pressing paper against the inked surface.

Intaglio prints (e.g., etchings, engravings, drypoints) are made

by forming grooves in a surface, forcing ink into the grooves, wiping

the rest clean and pressing paper against the surface so that the paper

picks up ink from the grooves. Surface, or planographic,

prints (e.g., lithographs, monotypes) are made by forming an image on

a completely flat surface and transferring that image to a piece of paper. Stencil prints (e.g., serigraphs) are

made by forcing ink or paint through unprotected areas of a guide, or

stencil, onto a sheet of paper, fabric, or other material.

Reproductions

have long been made by the process of offset lithography using large,

expensive printing presses to make copies rapidly and in large numbers

without directly involving the artist. These days, some artists are making

copies on ordinary office copy machines—since the artist may run

the machine to make the copies, it may sound as if that qualifies these

copies as prints, but let’s not stretch things that far! A more

recent way of making copies is the giclée process using a computer

and a special inkjet printer. Giclée copies are most often advertised

as prints, but they are in fact reproductions (admittedly high-quality

reproductions). Sooner or later artists will operate their own computer-printer

setups and personally introduce variations from one copy of an image to

the next that may qualify these copies as prints — stay tuned.

Prints are made in limited editions — that is, there are a fixed number of images made and no more. If, say, fifty copies of a particular image are made, the edition size is 50. Usually the artist signs and numbers each copy 1/50, 2/50 and so on, traditionally in pencil, which helps signal that the signing and numbering were not done by mechanical means. Signing and numbering each copy gives the buyer some assurance that the artist has personally viewed and approved each one. It’s become widespread practice to sign and number reproductions in the same way — in that case, signing does not imply that the artist actually had a hand in producing the copy, but only that he or she did look at each copy and that the number of copies to be sold is limited to the stated edition size. The term “open edition” means there is no limit to the number of copies that will be produced; in this case numbering the copies would be meaningless.

|

|

Despite the significant differences between prints and

reproductions, “print” has become the word of choice for any

copy and these days you’ll find many people at art fairs selling

“prints” that are really reproductions. Why?

1.

Prints sell better. “Reproduction” has a cheap connotation

and, given a choice, a buyer will almost always choose a print over a

reproduction. Much of the buying public doesn’t know the difference

between the two. If you label your reproductions

“reproductions” and the guy in the next booth labels

his reproductions “prints” — other things being equal

— which of you do you think will attract more buyers?

2. Ignorance. Not only does the public not

know the difference between a print and a reproduction, but neither do

many so-called artists. In my painting classes I talk about this, hoping

to do a little to inform the next generation of artists, but it’s

a tough battle. People simply prefer to say print!

Which leads me to the next point:

3. Print rolls off the tongue more easily

than reproduction. Why use

a four-syllable word when you can use a one-syllable word? Sorry to say, I catch myself occasionally

swapping the simple “print” for the formidable “reproduction”

in casual conversation.

4. In photography, print is the accepted

word for any number of copies of an image and it’s easy to understand

the carryover from photography to printmaking.

Our

language is rich and constantly evolving and, as Martha Stewart might

say, that’s a good thing. But I think there’s a big difference

between decent evolution and plain dumbing-down. Just because most television

commentators say “lay” when they mean “lie” and

“these kind” when they mean “this kind” doesn’t

mean we have to alter our language to accommodate them. Art should be

a place where quality and honesty still count for something, so please,

let’s at least get our terms right.

(Phil

Metzger, artist, teacher, and author of several art books, lives in Rockville,

MD. You’ll find much more on printmaking and specific kinds of prints

in his book, The Artist’s Encyclopedia, available from North

Light Books, at 1-800-289-0963.)

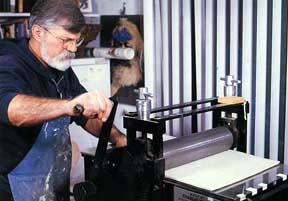

Maryland

printmaker Peter Stoliaroff at his Charles Brand etching press.

The same press can be used for pulling other forms of prints, including

engravings, drypoints and embossings. (Photo permission of Peter

Stoliaroff)

Maryland

printmaker Peter Stoliaroff at his Charles Brand etching press.

The same press can be used for pulling other forms of prints, including

engravings, drypoints and embossings. (Photo permission of Peter

Stoliaroff)  Line

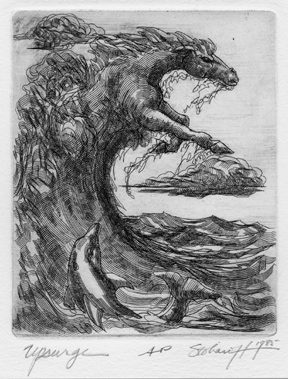

etching "Upsurge" by Peter Stoliaroff, 4 1/4" x 4".

Permission of Peter Stoliaroff, whose work may be seen in Phil Metzgeršs

book, The Artistšs Illustrated Encyclopedia, North Light Books,

Cincinnati, 2001

Line

etching "Upsurge" by Peter Stoliaroff, 4 1/4" x 4".

Permission of Peter Stoliaroff, whose work may be seen in Phil Metzgeršs

book, The Artistšs Illustrated Encyclopedia, North Light Books,

Cincinnati, 2001