(845) 246-6944 · info@ArtTimesJournal.com

|

|

Nancy Catandella at The Gallery at R&F

By RAYMOND J. STEINER

April, 2002

SOME TWENTY-ONE portraits – including a self-portrait – comprise this exhibit, each one a part of a series ("21st Century Icons") that binds them into an artistic whole. Though they can be viewed individually as separate statements (each is a self-contained portrait of a friend or relative of the artist), and a work that is fully capable of standing apart from the "set," my sense is that their full power can best be experienced when exhibited side-by-side – i.e., hung in a group as they appeared in the exhibit. In the aggregate, these "icons" exert a powerful influence, appearing as a mysterious gallery of faces that inevitably call to mind the ancient Fayum portraits of ancient Egypt. Partly, the reason for the resonance is Catandella’s use of encaustics (the very same technique used in ancient Egypt and Greece), but also, as with the Fayum paintings, their purpose is to serve as immortal remembrances of beloved friends and family.

Though not thoroughly conversant with the encaustic technique, I am aware of the fact that wax and pigments, applied through the use of heat (the word ‘encaustic’ is related to the Greek enkaio which means to ‘burn in’), are implemented in their execution. In ancient times the use of encaustic was widely used because it lent itself to naturalistic effects, an important element in the making of portraits, but, as the story of Apelles and his ‘realistic’ grapes illustrate, equally effective in the literal rendering of still lifes. The ancient formula for encaustics has long been lost to us, but since a revival of interest in the medium in the late 19th century, many artists have attempted to rejuvenate the practice. Modern formulas (and its uses) have been derived from early literature (much, for instance, from Pliny); consequently techniques and materials tend to differ from practitioner to practitioner, each artist following his or her own dictates.

|

|

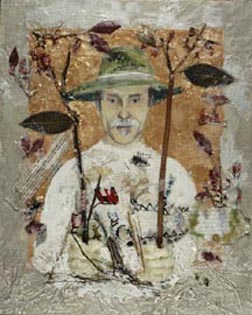

Catandella appears to use raw plywood as a ground, ‘building up’ her painting by a layering of successive applications of pigment and wax. Though most are "flat" (like ordinary paintings), they all resemble low reliefs in that they all have distinct three-dimensional (sculptural) qualities; some, like "Born a Traveler-Ferris Cook," obviously so with the subject's fingers and nose boldly protruding into the viewer’s space. I am not sure if these layers of wax/pigment are applied over a preparatory ground (such as gesso) or put directly onto the raw surface of the wood. Each portrait is set within a painted ‘mat,’ the colors and details of which seem to have some personal significance to the sitter.

In addition to this ‘framing’ device, Catandella also affixes a combination of materials (other than wax/paint) in collage-like fashion, again with these objects having apparent importance to the subject depicted. Thus we find such things as painting tools (brushes, knives), twigs, ribbons, paper, colored stones, leaves, flowers, pieces of glass, pottery shards, feathers, beads, a full necklace, foil, shells, bits of metal, a museum entry card, ballet slippers, playing cards, and even a stuffed animal (penguin) embedded in (or affixed to) the various paintings. From both these added items and from their titles, we are invited to arrive at an impression of the sitter, an impression that means to go far beyond the usual ‘likeness’ one expects to gather from a portrait.

Whatever one may derive from a single portrait, in their entirety these "21st century icons" exert an almost eerie impact. Each rendition is a full frontal view, the subject sitting foursquare with eyes gazing directly into those of the viewer. As we pass from one to the next, all hanging at the same level in an almost militaristic conformity, it feels as if one is passing through a house of worship, each ‘framed’ effigy staring at us as we go by, the effect much as we might experience while contemplating the "Stations of the Cross" or viewing statues or paintings of Saints while in a church. We know that in each separate portrait we are looking at the face of a mortal being, yet, when considered in their totality, one is left with a sense of having experienced a deeply religious 'happening.'

|

|

Some fourteen years ago I had occasion to meet and profile Nancy Catandella (September 1988 Issue of ART TIMES) and it is interesting to see how her work has evolved since that time. When I interviewed her, she was already well launched into making her living as an artist and teacher. In my profile I noted her work with the figure and wrote that her "desire to set a mood, to capture some undefinable matrix in which her figures would be embedded, seems to have been less a means of giving a ‘psychological’ depth than it was an attempt to come to grips with the mystery of how humans relate to their contexts … In another sense … she has discovered that sacred force which for her informs all of life and it is this vision she is attempting to share in her paintings. It is not the image – the icon – which is paramount, but our relationship to that image…"

Catandella's "21st Century Icons" appears here to bring into full bloom those early efforts of elevating the figure into some kind of "sacred" place. Not only is each of her subjects "spiritualized," but, in fact, elevated into the status of "consecrated" icons – a transformation that she fully expects her viewer to discern. Though the artist has given each one of her subjects (including herself) their allotted tribute in the form of artifacts germane to their earthly being, it is for the viewer to complete the process of veneration by participating in her vision of what it ultimately means to be "made in the image of God."

*"Nancy Catandella: 21st Century Icons: Encaustic Portraits (thru Mar 30): The Gallery at R&F, 506 Broadway, Kingston, NY (845) 331-3112. To contact the artist directly, call her studio at (845) 255-7990.