Art Critique:

Jerry Pinkney at The Norman Rockwell Museum

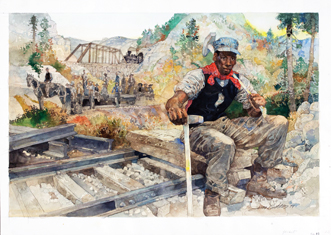

Cover illustration for John Henry, Jerry Pinkney, 1994. ©1994 Jerry Pinkney Studio. All rights reserved. Cover illustration for John Henry, Jerry Pinkney, 1994. ©1994 Jerry Pinkney Studio. All rights reserved. |

By RAYMOND J. STEINER

ART TIMES Jan/ Feb 2011

IN SPITE OF the long-standing assault on representational art, abstraction and its adherents have still not managed to silence the human need for “telling a story” in pictures. They might have divined the tenacity of representational artists hewing to the ancient practice of imagery had they only noted that we continue to give “picture books” to pre-schoolers who have not yet mastered the written word. It is, then, an innate human skill — if not need — to “read” pictures — a lesson that Jerry Pinkney has well learned and practiced for the past 50 years and which is amply borne out in this first major exhibition of his works, featuring some 140+ watercolors that cover a wide range of his overall oeuvre*.

Co-curated by Stephanie Plunkett , Deputy Director of The Norman Rockwell Museum and Dr. Joyce K. Schiller, the Museum’s curator for American Visual Studies, they’ve managed to gather representative works from Pinkney’s illustrations of children’s books (The Ugly Duckling; The Story of Little Black Sambo; Aesop’s fables; et al.), his African-American roots (Home Place; The Patchwork Quilt; et al.), Bible stories (From Psalms; Elijah; Noah’s Ark; et al.), and history (Song of the Trees; Escape from Slavery: Underground Railroad; et al.) as well as a collection of this award-winning illustrator’s memorabilia, artist’s supplies, and personal artifacts — all making for a visually delightful and informative exhibition.

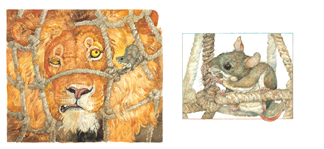

Illustration from The Lion and the Mouse, Illustration from The Lion and the Mouse,Jerry Pinkney, 2009. ©2009 Jerry Pinkney Studio. All rights reserved. |

Before we address Pinkney’s body of work — as noted, largely a selection from his various book illustrations — let’s take another look at that glib dismissal of representational artists as “mere illustrators”. Over the past 30 years or so that I’ve been reviewing, critiquing or profiling artists, the subject has often arisen — I recall a rather lengthy discussion with the internationally known portrait artist Everett Raymond Kinstler, when I profiled him for our pages in April of 1988. Kinstler, who in fact did begin as an “illustrator” in his early years, had therefore a profound insight into the question of representational artists being sloughed off as “mere” illustrators. As Kinstler pointed out, to dismiss the portraits of a Sargent, a Velazquez, a Rembrandt, as glorified “illustrations” is not only silly but insulting to the painting abilities of these artists. Like Sargent, Kinstler also does landscape painting, and one can hardly ignore the painterly qualities of these artists works. Of course, the die-hard abstractionist, may still say, “Well, a portrait of a person — or of a particular natural scene — is still “merely” illustration” — and equally obvious, the prejudice is unanswerable.

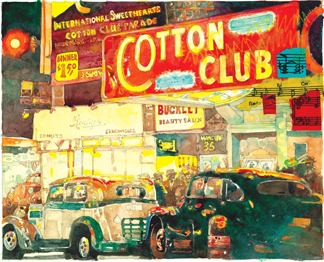

Illustration from The Sweethearts of Rhythm, Jerry Pinkney, 2009. ©2009 Jerry Pinkney Studio. Illustration from The Sweethearts of Rhythm, Jerry Pinkney, 2009. ©2009 Jerry Pinkney Studio. All rights reserved. |

Yet, to place an arbitrary division between representational and non—representation work as “non-art” and “art” respectively, simply flies in the face of history. As I note in this issue’s “Peeks and Piques!”, all art is a form of communication, representational — and especially as found in illustration — as well as abstraction. All imagery “speaks” to us — as surely as does an arrow on a sign or Michelangelo’s ceiling at the Sistine Chapel. One might just as well argue that Michelangelo’s muscular renditions of men and women in his ceiling mural are simple precursors of the characters found in, say, Marvel Comics — in short, that his art is “merely illustration” and that he is a “non” artist. It seems to me, then, that we ought do away with the false distinction and, in view of the fact that art by nature is communication, we ought to address what is presented to our eyes as images. By not allowing ourselves to be side-tracked by would-be art pundits to dismiss illustration as “comic-book” level “non-art”, we open ourselves to a rich tapestry of experiences.

If we agree that art must, in some fashion or other, “communicate” to us, then it is obvious that Pinkney’s paintings more than adequately fill the bill. In a given work, he, by definition, is visually communicating a particular author’s ideas, “translating” that author’s concept into an image, “telling” us the story through his eyes — the very path that art has taken from the beginning, indeed even before words were invented to carry the burden of communication.

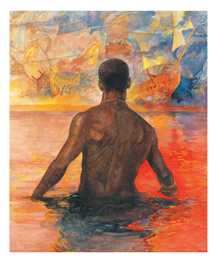

Cover illustration for The Old African, Jerry Pinkney, 2005. ©2005 Jerry Pinkney Studio. All rights reserved. |

More than simply (or should I say “merely”) communicating an author’s written intent, however, on a second level Pinkney is also communicating his intent — by the simple fact of choosing this particular image over that — or, as the title of this exhibition implies, Pinkney’s own personal act of “witnessing”. Who can say that the author of the story may have settled on that image, rather than on another? Thus, we are, in effect, given two stories, two levels of communication — the one the author originally wrote and the one that Pinkney — the illustrator as “witness”— has chosen to emphasize. More than emphasize, in fact, since Pinkney’s refined skills as both a refined draftsman and first-class watercolorist hold the viewer in their thrall — thereby enhancing an already captivating bit of “story-telling”.

Nor is this the end of it. If the author and the illustrator have both had their “say”, we still have to consider the viewer — i.e. you and me — as we move from one painting to the next. It is an axiom that the author’s — or, for that matter, the painter’s — intent is, in aesthetic matters, largely irrelevant. In other words, what Shakespeare “meant” in, say, Hamlet — is of less intrinsic value to the individual reader than what Hamlet says to that reader. It is this personal, individual “pay-back” that makes all art not only relevant but of inherent value to us. Therefore, when we stand before one of Pinkney’s watercolors, we not only “hear” the author and the painter, but — if we are in any way sensitive to what we are seeing — also “hearing” our own reactions, ideas, opinions, and evaluations — in brief, communicating on our level with the work of art before us, irrespective of what either the author or the painter “intended”.

Illustration from Little Red Riding Hood, Jerry Pinkney, 2007. ©2007 Jerry Pinkney Studio. All rights reserved. Illustration from Little Red Riding Hood, Jerry Pinkney, 2007. ©2007 Jerry Pinkney Studio. All rights reserved. |

After all is said and done, then, the art of Jerry Pinkney allows us — through its very clarity as communicative imagery — or as its detractors claim, “mere illustration” — to enjoy the very richness that art can offer, the multi-levels of appreciation that only good art can convey, the very elevation of spirit that even the ancients divined in “sharing the picture” — and that carries down to art-viewers of this very day. And, regardless of “chop logic”, the picture-book will continue to be the first means of communication that we will put in a child’s hand, thereby ensuring representational art a permanent place in both the artworld and in our lives.

*“Witness: The Art of Jerry Pinkney” (thru (May 30, 2011): The Norman Rockwell Museum, 9 Glendale Road, Stockbridge, MA. A catalogue of the exhibit is available: 96 pp.; 7 ½ x 8; B/W & Color Illus.; Exhibition Checklist. $17.95 Softcover.