By

RAYMOND J. STEINER

ART TIMES September

2007

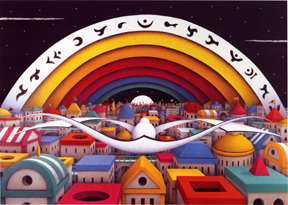

La Citta del Verbo (Oil on Linen) |

the

work of Pier Augusto Breccia first

came to my attention in February of 1985 at the Arras Gallery on 57th

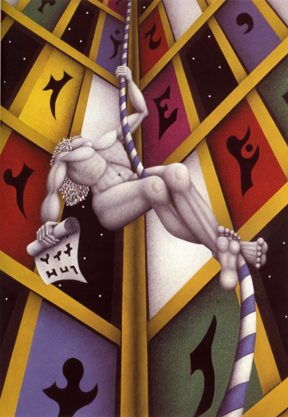

Street in New York City. Specifically, it was a painting entitled Icharus

that initially caught my eye — the theme of Daedalus’s son long

a personal symbol to me of what the serious artist ultimately represents:

viz. an inspired human being striving to reach the inevitably unattainable

source of light. Since that time, Breccia has returned to this theme of

the ultimate quest over and over — cf. The Broken Rope; The Fall;

Abisso; Lettera a Dio, for example — a leitmotif that speaks

not only for himself, or for other like-minded artists but, in an enlightened

world, also for all of mankind. As a whole, Breccia’s imagery depicts

man caught between two worlds — the one, divine (whole), the other,

earthly (fallen) — precariously walking a tightrope between salvation

and annihilation, perpetually suspended in a no-man’s world that is only

too familiar with its imperfections while yearning for a world beyond

the stars that he can only vaguely comprehend.

Yet,

try to reach beyond his grasp he must — no matter how many times

the jury-rigged wax affixed to his wings is doomed to melt — as

long as he has been given the directive to do so. Because it was thought

that the artist was somehow especially inspired (literally, “breathed

into) in Renaissance times, it was to the artist that the unlettered,

common man turned for symbolic guidance — if the Church spoke to

his heart and mind, it was the artist who spoke to his inner being, his

soul; if the priest dispensed the Word, it was the inspired artist who

could bring forth the Image. Mankind, being what it is in its “fallen”

state, however, has never been astute enough to tell the difference between

the valid and the invalid “answer” given him. In today’s world, of course,

such “inspiration” is scoffed at, and the artist reduced to a mere maker

of images, “genius” determined by the amount of money it brings the artist

rather than the degree of enlightenment that it might bring to the viewer.

Lettera a Dio (Oil on Linen) |

How

pleased I was, then, to learn of Breccia’s retrospective* coming up this

October at Rome’s prestigious Palazzo Venezia and, more especially that,

in the market-dominated artworld of today, he has not deviated from his

initial vision. As his title, “La Pittura Ermeneutica” (hermeneutic pictures),

indicates, Breccia has merely deepened his search into the mysteries of

the human condition.

When

I first met Breccia — some months after seeing his work and during

one of his visits to New York City — I learned that before he turned

his hand to painting he had been a heart surgeon — and not merely

a heart surgeon but the first and foremost such surgeon at the Catholic

University Hospital in Rome. I had only become fully aware of his former

status as a doctor after visiting him in Rome the following year, when

he offered to show me what he “did before becoming an artist.” When we

entered the hospital, Breccia was treated with not only respect but profound

reverence, and it was only then that I was made to understand by the staff

that an entire wing devoted to heart surgery was all “Dr. Breccia’s doing.”

I also learned that such was his reputation that it was Breccia who was

summoned to his side when Pope John had been shot.

“And

you left all this to become an artist?” I asked.

He

shrugged. “My family thinks I’m crazy. After all, my grandfather and my

father were surgeons — and even now, my son has followed in the

tradition.”

“Then

why the change?”

He

paused and looked into my eyes. “Raymond,” he said passionately, “even

when I held a human heart in my hands, I still could not comprehend the

mystery of life.”

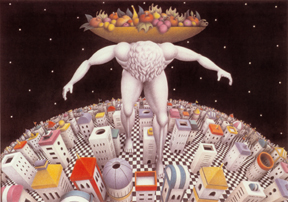

Qumran (Oil on Linen) |

I’ve

written at some length about Breccia’s life and artistic mission (“Profile:

Pier Augusto Breccia”, ART TIMES: July 1988; “Critique: Pier Augusto

Breccia at Arras Gallery, NYC”, ART TIMES: June 1991; “Pier Augusto

Breccia: Another Look”, ART TIMES: May 1997) and need not belabor

many of the topics covered in those articles other than to say that on

almost all points he has deepened but not deviated from what I have termed

his “heroic deed” of attempting to close the gap between the fingers of

God and Adam as so eloquently depicted in Michelangelo’s painting on the

ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Prometheus-like, Breccia, in his art, is

doing no less than trying once more to bring the “fire” of Divinity to

Mankind.

If

Breccia’s cosmology leaves no doubt about a divinity, there is a host

of problems concerning mankind’s mysterious relationship to that divinity.

What is man? What is his purpose? From whence did he originate? What his

ultimate destination? How may his apparent earthbound existence escape

into the ethereal sublimity of Heaven without paying the ultimate penalty

of Death? Clues — for Breccia — abound that there is, in fact,

a provident overseer, the bounty of Nature the most persistent motif in

his work. If the heavens are most often depicted as a sea of blackness

punctuated by stars, images of ripened fruit are always colorful, always

lush, always near at hand for the plucking. Still, if God is there, if

he cares enough to provide, cares enough to plant the desire of hope in

mankind, then why has He made the path to Him so dark, so distant?

Breccia

is still probing the mystery. And, although as an artist he is an autodidact,

he is not merely a one-time eminent surgeon, but also a classical scholar

and philosopher in his own right. Born in Trento, Italy in 1943, he showed

an affinity for the classics of ancient Greece and Rome. Before high school,

he had Dante’s Divine Comedy “by heart” and, during his first year

at the high school had translated and published Sophocles’ Antigone

and Aeschulus’ Prometheus Bound. The translation of Plato’s

Dialogues followed shortly thereafter. Though steeped in a classical

tradition, Breccia’s scientific training as a doctor has loosened some

of the bonds that have held him in thrall to both the wisdom of the ancients

as well as the teachings of the church. Yet, for all his learning —

and his desire for learning — he was well aware that the

mystery continued to elude him.

L’Ermeneuta (Oil on Linen) |

By

the late 1970s, it was clear to Breccia that, as advanced as his studies

had brought him in the field of medicine, pure science could not bring

him one step closer to solving the enigma of human life. A chance doodling

with a pencil as he sat at his desk pondering his dilemma slowly evolved

into an epiphany when he discovered that he not only could reproduce what

he could see, but also what he could imagine. Suddenly, the power

of the image came as a revelation — perhaps this might be

the path to discovery! Could it be true as the ancients believed —

and Otto Rank confirmed in his Art and Artists —that it was

the artist — the image-maker — who was the first priest? The

first to plumb the depths of his inner nature to discover his source?

Surely it is now evident that pictures predated language and that, “In

the beginning” it was the image and not the word. Did not art transcend

science, philosophy — perhaps even theology? As if by divine fiat,

the hands of the surgeon soon became the hands of an artist, and as his

hands and eyes developed in synchronic coordination, his skill to depict

what he saw in his mind’s eye quickly developed.

So

quickly did it grow, in fact, that by 1981, he had illustrated and written

his first manifesto, Oltremega (Beyond Omega), which was published

with an introduction by the Italian critic and poet, Cesare Vivaldi. The

book suddenly thrust him into a new life and career. His “new” eyes opened

up the world of art to him, but it was not long before he discovered that

the contemporary art he was seeing held little relevance for him. “Most

modern art shut me out,” he explained. “I did not care about an artist’s

private vision. I wanted to know what that artist shared with me —

what that artist could tell me about me.”

By

the age of forty-two, Breccia burned his bridges and resigned his position

as Chief Surgeon, fully launched on his mission of returning art to its

nascent purity, to return it to the task of bringing mankind into a better

understanding of his Divine Source. He had already been included in seven

different group shows (in both Italy and the United States), as well as

eleven one-man shows in Italy, two in New York City (at the Gucci Galleria

and Arras Gallery Ltd,), and one in Germany. Immediately upon his resignation

from the Catholic University of Rome, the Charles Jourdan Foundation of

Paris and the Arras Gallery of New York mounted a one-man exhibition in

Zurich, Switzerland, further widening his reputation as an artist. He

had also, during this four-year period, published Choral-Monologue

(Rome), L’Eterno Mortale (Rome), Transpersonal Painting

(New York and Zurich), Architectures of Logos (New York), and

Truth/Imagination (New York). At a lunch-meeting in New York City

in January of 1993, Breccia presented me with a major work, Animus-Anima:

La Cifra Pittorica dell’Ideomorfismo, the volume an impressive 10-lb

tome presenting his fully developed understanding of what his art represented

up to that point in time.

Central Park (Oil on Linen) |

For

all his erudition and literary skill, however, Breccia knew that, at bottom,

it would not be words but images that would deliver his message

to his viewers. From the absent-minded doodles that first appeared under

his pencil, Breccia has continually developed his imagery over time, re-interpreting

and re-inventing earlier symbols while bringing forth still new images

as they emerged from his subconscious mind. What he could not find in

the ancient philosophers, he sought in more modern thinkers, scouring

the thoughts of such men as Schleirmacher, Heidegger, Gadamer, Jaspers,

Levi-Strauss, Derridam, Ricoeur, and many others — all in an effort

to perfect his visual interpretation of the human condition. When he turned

his back on modern art, he also turned his back on the art of the past.

If such symbols as those produced during the Renaissance had served mankind

back then, they could have little or no relevance for today’s science-dependent

world. And, if today’s artists chose to merely “make pictures”, he was

determined to produce a personal orthography and symbolism that would

address the inner eye of his viewers, an iconography that would not only

delight but enlighten — if only the viewer would see. In

effect, the result of his studies has been the invention of his own language,

totally unlike that of any other since it reflects his own, unique vision

gleaned from the wisdom of thinkers from both the past and the present.

That

Breccia has now turned to hermeneutics — the science of Scriptural

and literary interpretation — to explain his body of work indicates

that he has yet taken a further step in clarifying his quest and in bringing

his vision to full fruition. As Breccia is well aware, however, mere words

— neither mine, nor his, nor anyone else’s — can ever take

the place of his imagery since it transcends verbal language. It is, in

every respect, its own language — as all visual art is and

always has been since its earliest manifestations in pre-history —

and must be taken on its own terms. In this sense it is sui generis.

And, in light of the fact that Breccia’s symbols are so personal,

it is no wonder that his art bears little or no comparison with that of

any other artist — either of those of the past or the present. It

virtually stands alone in the history of western iconography. Ironically,

however, as intensely personal as may be his imagery, Breccia’s message

is a universal one, open to all who choose to see — and it is this

that has made him grow both personally and professionally in stature.

L’Improbabile spazio dell”Esserci (Colored Pencil on Paper) |

During

a visit to his studio in Rome during the spring of 1997, Breccia shared

with me his belief that art is in crisis — that by turning it into

a commodity we have robbed it of its original wonder, its original purpose.

It was his dream to keep the body of his work intact, since to see it

in its whole is to grasp his intention of bringing the ancient wisdom

into alignment with today’s space technology, to make the link between

what we were, to what we’ve become, and to what we might still achieve

— cannot mankind, like Icarus, fly ever higher now that we have

the technology to produce better wax?

Little

wonder that Breccia’s latest maturation of expression has been first introduced

in Brussels (2003), then in Florence (2004) and now, in its fullest expression,

at Rome’s Palazzo Venezia under the auspices of the Ministero per i

Beni e le Attivita Culturali, promoted by Claudio Strinati, Superintendent

for the Roman Museums, and curated by Marisa del Re. Some 155 paintings,

including many preliminary drawings for both completed and projected works,

make up the exhibit, which by all indications promises to be a landmark

exhibition — not only for Pier Augusto Breccia, but also for the

future of art. Indeed, as I said in his 1988 Profile, “a need for heroes

and for heroic deeds…is not dead at all”.

*“La

Pittura Ermeneutica di Pier Augusto Breccia” (Oct 3—Nov 4): Palazzo

Venezia, Via del Plebiscito, 118, Roma. 06/86212211. A fully illustrated

catalogue accompanies the exhibition. More about Breccia and his work

can be found at pieraugustobreccia.it.