(845) 246-6944

· info@ArtTimesJournal.com

|

|

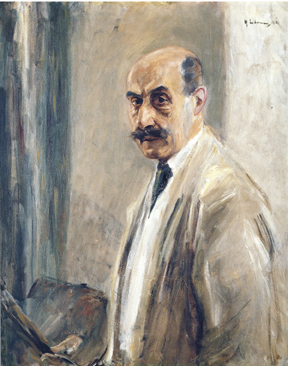

Max

Liebermann

at The Jewish Museum

Photos courtesy of the Jewish Museum

By

RAYMOND J. STEINER

ART

TIMES April 2006

SOME

FORTY-SIX works of the Berlin painter Max Liebermann — largely

oils on canvas, but a few on wood or cardboard, and ranging from 1873

to 1934 (the year before his death) which pretty much covers his development

from academic realism to what some have called “German Impressionism”

— are presently on view at The Jewish Museum in New York City.*

Gleaned from a total of sixty-two of the artist’s paintings recently

exhibited at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles (the organizers

of the exhibit), “Max Liebermann: From Realism to Impressionism” is

the first such comprehensive showing of the painter’s oeuvre to be seen

by American viewers to date.

As

representative of his ‘progress’ (one might question if indeed the evolution

ought to be characterized as progress in that word’s specialized sense

of ‘betterment’) from his early influences of such masters as the Hungarian

painter Mihály Muncákcsy and the Dutch genre painters to that of coming

under the sway of the French Impressionists and the newly-styled “secession”

painters, the organizers of the show have gone a long way toward bringing

to life a major German painter who has for the most part remained an

unknown element in this country. Whatever the final assessment of the

course of Liebermann’s art, there can be little doubt that the path

of his career was one of extraordinary accomplishment.

For

a Jew whose life and artistic career coincided with a country that was

determinedly attempting to establish its “pure” Teutonic roots, Liebermann

had come astonishingly far in establishing himself as not only a leading

painter, but also as a major force on the cultural life of Berlin, the

very center of a burgeoning German consciousness. Born into a Weimar

(i.e. a “democratic”) dominated society, Max Liebermann found his beloved

city slowly but inexorably transforming into one dominated by the rising

Nazi Party. That he was well respected enough to have been elected as

president of the Berlin Secession as well as president of the Prussian

Academy says as much of Liebermann the man as it does of Liebermann

the artist. Surely he was a presence to be reckoned with in a city filled

with a cultural elite that had its heart set on becoming residents of

the premier city in the new German nation. That it was fierce nationalism

that finally brought him down — branded as an “alien” whose work

was deemed “decadent” — speaks loudly and clearly that here was

indeed an artist who was at the wrong place at the wrong time. Liebermann

died a broken and demoralized man at the age of eighty-seven, just two

years after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor; his wife, Martha, took her

own life in 1943, on the eve of her forced deportation to Theresienstadt

.

Max Liebermann (Germany, 1847–1935), The Weaver, 1882, oil on canvas. Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt am Main. © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. |

However

much Liebermann’s personal force and charisma led to his rise as one

of Berlin’s cultural leaders, one can readily see how his art contributed

to that reputation. Paintings such as “Women Plucking Geese” painted

in 1872 (unfortunately, not included in the New York City venue), “Women

Cleaning Vegetables” (1879), “Workers in a Turnip Field” (also not in

this exhibit), or his much vilified and re-worked “The Twelve-Year-Old

Jesus in the Temple with the Scholars” (1879), reveal a painter at the

height of his powers, clearly in control of the tools of his trade.

Most of his early work, in fact, is masterfully executed in the traditional,

realist method. Even when he begins his exploratory forays into impressionism

(see, e.g., his “Study for Parrotman”, 1900) we find an artist still

intent on informing his viewers insofar as the impact of both form and

color in art can make us “re-see” nature. After such bold, realistic

statements, it is perhaps not too difficult to understand why such paintings

as both sketchy 1905 versions of “Jewish Quarter in Amsterdam” caused

such consternation and confusion to many of his contemporaries. Where

might they detect the skill in such “slipshod” handling of paint? After

all, one still had to be able to “read” what a painting conveyed, didn’t

one? How could an artist of such obvious talent turn his back on the

principles of academic draftsmanship and careful composition?

Max Liebermann (Germany, 1847–1935), Promenade on the Dunes in Noordwijk, 1908, oil on wood. Kunsthalle Bremen. © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. |

After all, this was a man who until recently was being sought out by Berlin’s upper elite — including President Paul von Hindenburg — to have their portrait painted by his hand. So far had he fallen out of favor in his later years, however, that it was only one of his upper-class sitters, Dr. Ferdinand Sauerbruch (along with the artist Käthe Kollwitz), that represented the non-Jewish members of Berlin’s society attending Liebermann’s funeral in 1935. Whatever he was trying to accomplish artistically, his moving from realism was to many an almost deliberate throwing down of a gauntlet in the face of a society increasingly growing in rigid conservatism. To the uncultured Nazi thug, it was already enough that he was a Jew, an Ausländer; must he also join the abominable ranks of what appeared to many as an untalented gang of would-be artists?

One cannot second-guess an artist’s intentions by either studying his life or his work — and even when taken in combination, there are simply too many variables that go into an individual’s aesthetic development to come away with any definite conclusions as to why this or that tack had been taken. Indeed, it is the rare artist capable of clearly stating or understanding why particular paths are chosen during an aesthetic journey. That Liebermann chose to move from the clarity of his early vision to one of suggestive ambiguity may have been the result of less aesthetic than of psychological impulses. It is true that he eventually pulled back from allowing his art to completely disintegrate into pure abstraction, that he ultimately rejected the expressionist movement, but the damage to his own aesthetic vision had already been done.

Max Liebermann (Germany, 1847–1935), Ropewalk in Edam, 1904, oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. © 2006 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. |

Assuming

that — as many artists do — he was attempting to communicate

through his art, what has he communicated to us? To this viewer, at

any rate, Liebermann conveys less of a firmer grasp of his art than

he does of a growing concern with a society that, as his move from clear

representation to indistinct abstraction may indicate, is slowly dissolving

before his eyes. As noted above, one might not view Liebermann’s development

as a move toward something “better”, but surely one can “read” his art

as a commentary on his social milieu. In this sense, as Liebermann’s

world collapses around him, so also does his art collapse into disjointed

blotches of color that confuse the eye as much as it informs it. In

the end, as his sphere of influence was circumscribed and his world

narrowed, he turned in on himself, confining himself to making paintings

of his beloved house and gardens in Wannsee. Sadly, the body of “impressionistic”

work that he produced in these last years is far removed from that which

had once revealed the power of both his vision and of his brush.

And,

again, assuming that he was trying to communicate through his art, what

better way than “breaking down” the rules of his academic training to

reflect the breaking down of rules in what he once considered a sane

and livable society? That he had to use his art as a weapon —

the only weapon he was allowed as a Jew — instead of as an instrument

of beauty and delight, is to my way of thinking more than a tremendous

loss, for it not only reveals Liebermann’s personal anguish but, because

of his undeniable status as a proven artist of renown, sets the stage

and clears the path for the many excesses which followed in his wake.

|

|

Who can deny that a good deal of today’s art bludgeons the viewer much

more often than it serves to soothe and elevate? Who cannot be repulsed

by art that glorifies ugliness for its own sake? Granted that early

masters — Goya, Daumier, Delacroix jump to mind — used their

art to enlighten, but today the art itself, when used as a blunt instrument,

merely shocks, enrages, disturbs, unsettles, enflames to such an extent

that we come away not better informed but merely more angry. Max Liebermann’s

life and art can offer no more graphic illustration of one terrible

instance of why this has occurred.

*“Max

Liebermann: From Realism to Impressionism” (thru Jul 30): The Jewish

Museum, 1109 Fifth Ave., NYC (212) 423-3200. (An illustrated catalogue

with the full complement of works from both venues is available. University

of Washington Press/Skirball Cultural Center: 232 pp.; 9 x 12; B/W & Color Illus.;

Chronology; Selected Bibliography; Index. $29.95 Softcover.)