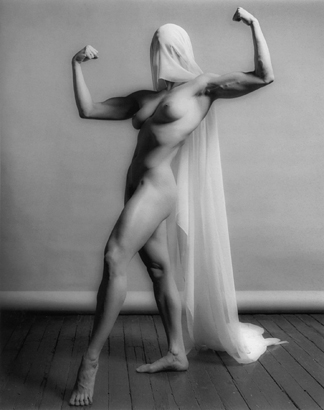

Robert Mapplethorpe, Thomas, 1987, gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 in (50.8 x 61 cm) ©Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. Robert Mapplethorpe, Thomas, 1987, gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 in (50.8 x 61 cm) ©Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. |

Michelangelo and Mapplethorpe

By Amanda Ruggeri

ART TIMES online Jan/ Feb 2010

MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI is renowned for his Renaissance masterpieces, often of religious subjects: the David, the Pieta, the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Robert Mapplethorpe, a photographer of the 1970s and 1980s, is remembered for his sexually-charged, often homoerotic images: statuesque nudes, rippled backs, a self-portrait with a bullwhip.

But the two men shared characteristics - and approaches to art - that stretched across time, as explored in the Galleria dell' Accademia's exhibit Robert Mapplethorpe: Perfection in Form, recently extended by popular demand to run in Florence until January 10.

The exhibit draws parallels between Mapplethorpe's works and the Renaissance era's aesthetic devotion to form, an interest hardly unique to Michelangelo. In the first room, a plaster cast of Giovanni Giambologna's 1582 Rape of the Sabines twists, tormented, next to Mapplethorpe's 1985 Ken, Lydia and Tyler. Both pieces center on three figures, one female, two male. Both play with curving lines, whether in three-dimensional or two-dimensional space. And both highlight their bodies' beefed-up musculature, but downplay their identities: Only one of the faces of Giambologna's sculpture can be seen at any one time, while Mapplethorpe cuts his figures off at the neck. But while Giambologna highlights the helplessness of his female figure, who rises, futilely, out of the victor's grasp, Mapplethorpe's photograph depicts solidarity. As implicit as the physical power of the two men is, it is also clear that any next move is one that the female would have to not only be complicit in, but control.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Derrick Cross, 1982, gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 in (40.6 x 50.8cm), © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. |

Still, the inclusion of other Renaissance artists seems almost an afterthought in the exhibit. And, to some extent, it should be: Mapplethorpe and Michelangelo have enough in common on their own. Mapplethorpe's images often depicted muscular men in frankly homoerotic settings. Michelangelo, too, had an apparent preoccupation with depicting beefed-up male nudes, so much so that even his female figures often look like men with pasted-on breasts. After he completed the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel in 1541, critics attacked it as scandalous for showing such copious amounts of naked flesh (the ever-ornery artist would punish one of them, the Vatican's Master of Ceremonies, by painting his face onto Minos, the judge of the underworld). Shortly after Michelangelo's death in 1564, the first of a series of "underpants painters" was hired to cover up the figures. And shortly after Mapplethorpe's death in 1989, controversy over his own work exploded as Washington's Corcoran Gallery of Art and Congress refused to go forth with a planned exhibit of his work. The next year, a Cincinnati museum director was put on an obscenity trial for having exhibited Mapplethorpe's work.

The exhibit in the Uffizi elides much of that history. And particularly since the exhibit coincides with the twentieth anniversary of Mapplethorpe's death from AIDS, excluding these details seems not only incomplete, but almost offensive. But focusing on the art alone allows the exhibit to keep the emphasis on the relationship of art across the centuries, not on history's persistent cycles of rebellion and reaction.

In a room devoted to sculptural form, for example, Michelangelo's studies of nudes are counterpoised with Mapplethorpe's images. The dark, shining back of Derrick Cross (1983) parallels Michelangelo's River God (1525), a model of a muscled torso done in black wax. As the pieces intimate, both artists were interested in fragments of form: Michelangelo in his studies for larger works, Mapplethorpe as the complete piece itself. Michelangelo's Studies for the Expulsion from Paradise (1510) shows a left arm here, a hand there. The limbs are difficult to parse by gender. Nearby hang Mapplethorpe's Alistair Butler (1980) and Lisa Lyon (1982), each close-ups of a heavily muscled hip and arm in profile. It takes a second glance to know which figure is which gender-but compared to the beauty of the forms, the question itself is secondary.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Thomas, 1987, gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 in (50.8 x 61 cm) ©Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. Robert Mapplethorpe, Thomas, 1987, gelatin silver print, 20 x 24 in (50.8 x 61 cm) ©Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. |

With the David (1504), of course, the exhibit finds its climax. Michelangelo's masterpiece rises victorious, cool and calm, as it has for four centuries. But this time, it's anchored by four modern photographs. Mapplethorpe's Ajitto series (1981) depicts a black male nude, hunched into a near-fetal position, from four different angles. The setup isn't perfect; each photograph should correspond with a different view of the David, which it doesn't. But the overall effect works: It is as if Mapplethorpe's male has risen from his crouch into the triumphant pose of the David, fully realized. And the photographs, with their sublimated posture, don't attempt to compete with Michelangelo.

And neither does Mapplethorpe. Even so, the exhibit underscores just how much he learned from the Renaissance master. "I'm looking for perfection in form," Mapplethorpe once said. "I do that with portraits. I do it with cocks. I do it with flowers." "He loved not only human beauty, but universally every beautiful thing," Ascanio Condivi writes of his contemporary Michelangelo, "choosing the beauty in nature as the bees gather honey from the flowers, using it afterwards in their works." Whether beauty is in the grace of a tulip or a tricep, a lump of bread or a breast, is up to the viewer to decide.

The exhibit runs at the Accademia until January 10, 2010. It will be at the Museo d'Arte della Città di Lugano - Villa Malpensata from March 20 to June 13, 2010.

(Amanda Ruggeri is a freelance art and travel writer who lives in Rome, Italy.)

Send your comments to info@arttimesjournal.com