(845) 246-6944 ·

info@ArtTimesJournal.com

By INA COLE

ART TIMES May 2007

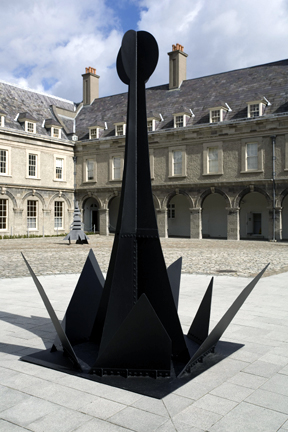

The Tall One by Alexander Calder |

ALEXANDER CALDER was one of the most prolific sculptors of the twentieth century, whose fluid configurations redefined the parameters of modern art. Born into a family of artists in Pennsylvania in 1898, Calder’s dexterity in manipulating materials soon became apparent and although he initially studied engineering, knowledge gained in this area was ultimately utilized in his pursuit of new forms in art. He enrolled in the Art Student’s League, New York, but departed for the experimental nucleus of Paris in 1926, where he met some of the greatest innovators of the twentieth century, including Arp, Miró, Duchamp and Mondrian. During these seminal years, Calder and his contemporaries changed the face of art, and it was in this unparalleled city, spinning with creative energy, that the quest to challenge accepted modes of representation and intellectual perception took place.

At this time the growth of Paris was truly remarkable. More than a utilitarian alternative to the country, it was the only place to be: the centre of money, culture and entertainment. However, this new found exhilaration has to be understood in the context of damage wrought by the First World War, where some 15,000 square kilometers of France had been laid waste. The French government, borrowing from Britain and the US, supplied generous advances for companies to invest and expand, and consequently by the mid 1920s prosperity had significantly recovered. A large foreign work force was imported and to cater for all its ethnic groups, Paris had to transform itself into the most cosmopolitan of European cities. Paradoxically, it was also one of the most expensive cities in the world with low standards of modern comfort for the majority, which contrasts sharply with its reputation as a centre for intellectual and artistic development. Nonetheless, with a surplus of available studios, Calder and his contemporaries who chose the bohemian life of Montparnasse seemed to exist on a dizzy high. At this time foreigners accounted for at least half of the artist population in Montparnasse and most of the artists of the School of Paris were not French at all; rather the term came to be synonymous with the work of immigrant artists resident in Paris between the wars.

Moving away from preordained formal structures, Calder’s work was perhaps particularly unusual in that it could be enjoyed, and he would arrive at Paris exhibition openings with a bale of wire, pliers and shears and entertain his contemporaries by creating a new batch of works during the course of the evening. This inclusive approach resulted in many significant friendships, particularly in relation to the popularity of Cirque Calder. Prior to his arrival in Paris, Calder had spent time sketching at the Ringling Brothers Circus and Cirque Calder was a continuation of his observations, which evolved into a complex assemblage of diminutive wire characters, manually operated in elaborate performances lasting about two hours. As an art form its versatility was unique, as all the pieces could be packed into a large trunk and carried between Paris and New York. As a result of these groundbreaking inventions with wire, Calder’s reputation escalated and he consequently spent much time crossing the ocean to attend exhibition openings in New York, Paris and Berlin.

In the mid 1920s Paris became a vibrant centre for dance and music, with many new sounds, such as Jazz, which was a vital part of the entertainment. This reached a climax in 1925 with the arrival of the American company La Revue Nègre and its flamboyant star Josephine Baker. She typified the stereotype of the black burlesque figure, with banana belts and exotic plumage, and as a result of the excitement created by her performances nightclubs like La Jungle opened in 1927 excelling in ragtime and blues. The essence of this period is epitomized in Calder’s Josephine Baker; one of the first wire sculptures he created on his arrival in Montparnasse. It emits a joyousness, which makes it a particularly appropriate period vignette, and reveals an irrepressible sense of the comic combined with an economy of means. This is a drawing in space, where the pencil line has been replaced by a fluid manipulation of wire, created with an obvious mastery of draftsmanship. The void has replaced the mass and the empty space within and around the work becomes as important as the shapes of the wire twisted to represent the figure. There is a sense the work may have been a spontaneous experiment, as it combines a synthesis between Calder’s inherent playfulness and technical knowledge gained during his studies as an engineer, and can therefore also be seen as an important stepping stone in the subsequent development of his work.

Calder single handedly went on to create an art form without precedent; the mobile, the first of which came into being in 1931. It was around this time he joined the Abstraction-Création group to which Mondrian also belonged, and it was on a memorable visit to Mondrian’s Montparnasse studio in 1930 where Calder had remarked, ‘I was completely taken aback by his studio; it was so huge, beautiful and irregularly shaped, its white walls split up by black lines and brightly coloured rectangles, just like his paintings… and right then I thought, if only everything could move!’ (V. Bougault, 1997, Paris Montparnasse). The result is well known, as Calder understood the logic of geometric forms in the same way he understood the logic of weight and counterweight, and the development of his work from assemblage to mobile, with an emphasis on dissymmetry was a crucial new development in twentieth century sculpture.

Alexander Calder and Juan Miró |

Although Mondrian’s compositional experiments were largely responsible for steering Calder towards abstract form, the term ‘mobile’ had initially been given to these works by Duchamp. The first of Calder’s kinetic constructions moved by a system of cranks and motors, but the mechanism was abandoned when Calder discovered the mobiles could oscillate freely with air currents, thereby offering an element of uncontrolled surprise in their infinite combinations. He believed that in the same way form and colour had long been a compositional element in painting, motion could be similarly composed in the making of sculpture; not simple rotary motion, but motion of different types and speeds composed to create a resultant whole. To achieve this Calder experimented with a system of weights and counterweights using balls, discs and freeform shapes, hung off-centre at the extremities of wire frames to facilitate air currents. These dynamic configurations were a fusion of lyrical harmony and mathematical precision, but made with the close alliance between physics and aesthetics a constant underlying concern.

From the mid 1920s Montparnasse had also become a centre for the Surrealist movement, spearheaded by the poet André Breton, and it was in this climate that Calder and Miró first met in 1928; a friendship sparked by their shared sense of iconoclasm. Miró introduced Calder to Surrealism, and although Calder’s association with this group is rarely documented, biomorphic and celestial forms notably entered his imagery at this time. Indeed, prior to arriving in Paris, Calder’s early fascination with the mysteries of the night sky, alight with planets and stars, influenced the iconography of his later work, which naturally had an affinity with the way the Surrealists questioned reason, using dreams and automatism to create a new reality. Miró and Calder had a unique appreciation of each others work, with similarities apparent in the dancing rhythm and precarious balance of their chosen forms, often defying gravity in their arrangement. An exhibition of Calder’s work at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin (to 30 June) shows his sculpture alongside Miró’s, thereby revealing the visual dialogue at play in their work. The theme for this exhibition derives from their friendship — a matter of vital artistic importance, well documented in the annals of art history. Even after Calder’s return to the US, these great artistic inventors maintained contact by correspondence and visits across the two continents until Calder’s death in 1976.

The euphoria of the 1920s

petered out in the advancing wasteland of the 1930s, largely due to the

Wall Street Crash of 1929, which created a global Depression. Although

this did not affect France until 1932, the effects lingered on throughout

the 1930s, until Europe became engulfed by the Second World War, which

threatened to be even more horrific than the last. Calder left Paris in

1933 and moved to Connecticut, where he remained. It was here that his

work became increasingly ambitious, evolving to the creation of large-scale

stationary constructions of welded and riveted sheets of metal, the predecessors

of which had originally been named the ‘stabiles’ by Arp.

While the oscillating mobiles danced elusively, the unpredictability of

the stabiles lay in how they seemingly changed shape when walking around

them, and with demand for public art high after the war, Calder was commissioned

to create stabiles for many worldwide locations. By the 1960s his reputation

had soared to global proportions, but Calder’s formative years in

Paris remained central to his later development, with loyalty to friendships

made during that time unceasingly enduring.