Rodin:

A Magnificent Obsession

at

the Albany Institute of History & Art

By

RAYMOND J. STEINER

ART TIMES November 2005

“…A

LOVER WHO could not be resisted.” So said Rainer Maria Rilke in his

love/hate paean* to Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) written during his extended

stay at Meudon as personal secretary beginning in 1902 and ending in

1906, when, also according to Rilke, he was “dismissed like a thieving

servant.” In truth, so much has been written about Rodin that it is

somewhat of a problem to get beneath the anecdotes, the lionization,

the reams of adjectives that have been lavishly strewn in his wake by

admirers and detractors (both those who have known him and those who

have not) to get to see the man behind the mythos that has grown up

around him. In the end, of course, it is less the man than his work

that matters most to us and, with some 70+ bronzes — from maquette-sized

studies to monumental works — the present exhibit at the Albany

Institute of History & Art* affords an exceptional opportunity for

us to come away with a more than adequate impression.

|

|

To

begin with, organized as they are into related themes (“The Gates of

Hell”; “The Burghers of Calais”; "Balzac”; “Hands”; etc.) spread

throughout the half-dozen or so galleries devoted to the exhibition

makes for easy viewing — the order imposed certainly nothing like

Rodin’s studio and grounds which, like many sculptor’s environs, had

more the hodge-podge appearance of disorder found in used car lots.

Secondly, a certain amount of order is also imposed in view of the fact

that these pieces represent the individual tastes of collectors, viz.

Iris & B. Gerald Cantor whose foundation both organized and

made possible the exhibit (funding and support was provided by Sponsor

First Albany, Omni Development Co., Inc., Lois and David Swawite, M&T

Bank, and Mountain View Group). Nevertheless, ignoring the artificial

categorizations and taking the time to study Rodin’s works as discrete

entities does leave the viewer the freedom to come away with a personal

impact.

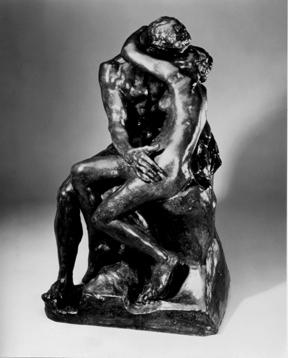

In

point of fact, many of the works included in the exhibit are indeed

discrete pieces — in one instance just hands, in others, partial

figures — each, however, capable of standing on their own as complete

and integrated works of art, such being the potent power of Rodin’s

ability to “speak” through his creations. The question is whether in

partial or monumental completion, what does his work say?

For

this viewer, I come away with considerable disquiet inasmuch as a great

deal of Rodin’s work seems to bespeak an unclear vision of just what

the human figure is. Certainly he does not ascribe to the Greek

ideal or its offshoot, Italian Renaissance art, with their belief in

the perfection of man. This is not to say that he cannot follow in the

very large footprints that they left in Western art — every so

often we come across in the exhibit what may be called for lack of a

better term, “finished”— that is to say, with a “polished” exterior

such as that in “Idyll of Ixelles” or “The Sirens” (Cat. Nos. 13, 89,

respectively) as well, of course, in pieces not included such as “Fallen

Caryatid with Stone” (Cat. No. 142), “Mme. Morla Vicuña” (Cat. No. 147)

or “Thought” (Cat. No. 131) all carved a la Carpeaux from marble, the

first a promised gift to the Cantor Collection, the other two in the

Musée Rodin, Paris. The latter examples are, as noted, carved from marble

and by all indications Rodin’s preference was for modeling his pieces

in lumps of clay.

Perfection

in the human figure, in any event, seems not to be Rodin’s ultimate

vision of mankind. Instead, his “magnificent obsession” appears to show

mankind in a state of becoming, a state of striving toward some completion

that he cannot as yet foresee. Figures are not only contorted into “inhuman”

shapes, but often far from anatomically correct. Abnormally elongated

limbs and necks or an awkwardly realized upper torso in, e.g., “Jean

d’Aire, Nu” might give rise to the mistaken belief that the artist simply

doesn’t know any better. Rodin’s figures — whether real or imagined

— are not, properly speaking, “beings” at all, but rather rough

drafts of them. For all its apparent order, strolling through this exhibit

is like wandering through some earlier prototype of Eden in which a

confused Creator is hastily lumping earth together and still seeking

his ultimate “intelligent design”. That Rodin knew his anatomy, however,

can clearly be seen not only in those pieces more classically executed,

but also in his drawings, several of which are in the exhibit (see especially

the engravings “Antonin Proust”, and “The Ring” (La Ronde).

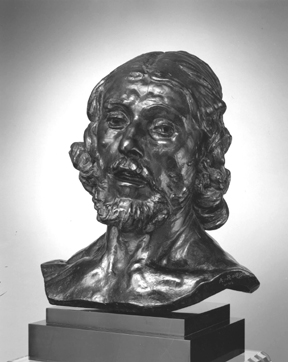

Even

taking into account that many of the studies in the exhibit were intended

for his masterwork, the “Gates of Hell”, in which convulsed figures

seem de rigueur, one looks in vain to find classical beauty in

his modeled works. One can only assume, therefore, that Rodin’s figures

are exactly what he intended them to be — a realization that becomes

even clearer when we see the several studies that often precede final

versions, a fact made especially evident in the “Balzac” gallery and

the variations he went through before settling on the Balzac he envisioned

(“envisioned” since Rodin never actually met the great author). In no

instance do we find a hint of idealization.

Yet,

if we cannot find classical beauty, there is little doubt that

we find another kind of beauty — that of Michelangelo’s terriblita,

a kind of overpowering grandeur that lies at the heart of raw creativity,

that creative cauldron from which all art arises before it is imprinted

(and modified) by human consciousness. Indeed, many of Rodin’s pieces

are reminiscent of the great Italian sculptor’s half-finished works,

those awesome figures forever encased in and breaking free from their

stony origins. The impact of Rodin’s vision of ‘dead matter coming to

life’ is most vividly experienced in the monumental conceptions, several

of which (“Fallen Caryatid with Stone” (so different in aspect from

the work of the same name carved in marble), “Whistler’s Muse”, and

the especially awe-inspiring though partial “Monumental Torso of the

Walking Man” — this last, it seems to me, to sum up Rodin’s true

genius of forcing his viewer to see man in all his awesome “becoming”.

|

|

In

a sense, from what we know of Rodin the man, his bronzes — his

gallery of prototypical human forms — might be seen as an extended

self-portrait. Rough-hewn and often ill at ease with his Parisian sophisticates,

Rodin made little effort to exude a “polished” surface himself. He knew

himself also to be not yet fully realized, a living example of the work-in-process

— the human being who still has to grow into his idealized state.

This

is a rare occasion for not only upstate-New Yorkers, but for all those

who do not anticipate a trip to France in the near future to get a close-up

look at the work of one of the major figures in the annals of modern

art. While you’re visiting “A Magnificent Obsession”, take the time

to watch the 53-minute award-winning video, “Rodin: the Gates of Hell”,

that presents a dramatic showing of the 10-step lost-wax casting process

that chronicles the project. This is a show you ought not miss, and

kudos to all those who made it possible as well as to the Albany Institute

of History and Art for taking the time to present it to the public.

*Auguste

Rodin: Rainer Maria Rilke. (Archipelago Books, 2004. Translated

from the German by Daniel Slager). Pgs. 73, 26.

**“Rodin:

A Magnificent Obsession, Sculpture from the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor

Foundation” (thru Dec 31): Albany Institute of History & Art, 125

Washington Ave., Albany, NY (518) 463-4478. A fully-illustrated catalogue

is available: Rodin: A Magnificent Obsession by Kirk Varnedoe

et al. 192 pp.; 9 ½ x 11; B/W & Color Illus.; Checklist;

Index. $29.95 Softcover.