(845) 246-6944 ·

info@ArtTimesJournal.com

|

|

at the New York Historical Society

By RAYMOND J.

STEINER

ART TIMES November 2008

Archibald Robertson View up Wall Street with City Hall [Federal Hall] and Trinity Church, New York City, ca. 1798 Watercolor, black ink, and graphite on paper 81/2" x 113/4" |

In

addition to the drawings and paintings that make up the show, Olson has

included such artifacts as paint boxes, palettes, paint brushes, conté

crayons, traveling secretaries (one that belonged to John James Audubon),

sketchbooks (be sure to stop and look at Joshua Rowley Watson’s —

Cat. Nos. 28a and 28b — and the computer thing-a-ma-jig that contains

the entire book and allows you to magically — at least, to me —

turn its pages) and such tools of the serious draftsman’s trade as rulers,

squares, calipers, and leather carrying-cases, among other paraphernalia.

I use the word “serious” consciously, especially since the art of fine

draftsmanship has fallen into such discredit in our day. Draftsmanship,

in fact, and its historical course in and on the American artscene, is

one of the major motifs this exhibition is tracing — one need only

leap from, say, the detail in delineating the ship in the right foreground

of “Novum Amsterodamum (New Amsterdam, New Netherlands)”, 1650

(Cat. No. 3) attributed to Laurens Block to the sketch by Robert Henri,

“Two Figures Walking”, undated, (Fig. 127.1) to see — granted the

difference in intent — how far those draftsmen’s tools of yesteryear

have been put out of use — and it is this particular thread of draftsmanship

— or, “rewarding trail…through this treasury” as Dr. Linda S. Ferber,

Executive Vice President and Museum Director, phrases it — on which

I should like to concentrate my attention in this review — it is

a “rewarding trail” indeed.

The

subject of draftsmanship, as many of my readers know, has enjoyed recurrent

visitations in these pages, there having been few of any major drawing

exhibitions in and around New York City that I have not covered over the

past twenty-five years. I heartily agree with Ms Olson’s observations

in her concluding paragraphs of the introductory essay to the catalogue:

“Drawings are unrivaled in demonstrating the touch of the artist and revealing

insights into the creative process.” (pg. 31). And yet, in spite of these

truths and in defiance of its long history as being the foundation of

all “fine” art, draftsmanship has come upon hard times in America since

the advent of modernism. Like English Majors who come out of college who

still can’t spell, it has become a commonplace that Art Majors graduate

who cannot draw a figure. Whatever this has done to American art in general,

it sharply points up a major problem in defining an “American Art” at

all. If, as Olson points out, drawing reveals “insights into the creative

process”, what exactly has that process been in America? What, in other

words, is “American” about our art? Olson notes (pg. 21) that the Hudson

River School was “America’s first indigenous group of landscape painters”.

This may be so, but to anyone living in the Hudson Valley Region (as I

have since 1945), there is little in the polished (the old-timers used

to call it “licked”) surfaces of their paintings that resemble the raw

and largely untamed landscape of the area. This is so because the original

“Hudson River School” of painters — Cole, Church, et al.

— were trained in Europe by European masters who taught in the Royal

Academies of Düsseldorf, Munich, Paris, Rome, London — in art capitals

that had ruled the (art) roost for hundreds of years. If Cole —

the “father” of the “Hudson River School” — painted vistas of the

Catskills, he did so with a European and not an “American” eye.

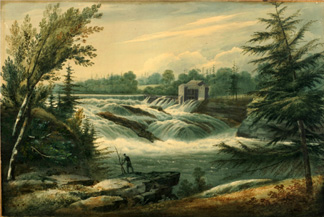

William Guy Wall View of Baker’s Falls, New York: Preparatory Study for Plate 8 of “The Hudson River Portfolio,” 1820 Watercolor, selective glazing, gouache, graphite, and touches of scratching-out on paper, laid on card, laid on canvas 14 x 207/8" |

The

search for such an “eye” was a common topic among American artists during

the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Most knew

that art patrons only bought European art and ignored American artists

(they were too ‘rough’ — hence the originally derogatory term “Hudson

River Artists” by the more genteel salon New York City artists who thought

it uncouth to tramp around the woods) — so they aped European motifs

and style. A glance over the checklist for this exhibition plainly tells

the story — out of the 127 (some were anonymous) that I counted,

only thirty-six of them were native-born Americans — all of the

rest were from elsewhere, from places like England, France, Holland, Germany,

Italy — even our vaunted John James Audubon (the Society has a wonderful

collection, incidentally) was from the West Indies while our equally revered

John Singer Sargent was born in Florence, Italy — all of whom were

drawn to America to ply their skills.

Some claim that we did not have an authentic

“American” voice until the advent of the so-called “Ashcan School” —

but William Merritt Chase, a student at the Royal Academy in Munich, had

been doing New York City street-scapes years before the “Eight” came on

the scene, and we need only to glance at such artists as Raphael Soyer

(born in Russia) and his “Park Scene with Figures on Benches, 1931)” (Cat.

No. 142) or Lionel Samson Reiss (born in Poland) and his “Going Home (Near

Bloomingdale’s at the 59th Street Elevated Station), New York

City” c.1946 (Cat. No.140) to see how “American” the aesthetic visions

of Henri and his group actually were. (From across the room, I was sure

that Reiss’s “Going Home” was a Reginald Marsh!)

Ironically, it was just when American artists

seemed to be coming into their own, in arriving at a distinctly “American”

voice, that the 1913 “Armory Show” knocked everything helter-skelter.

New York City might have been laying claim to becoming the new art capitol

of the world, but it was Europe once again which left its imprint on American

art. In the mad rush to be au courant, artists abandoned any and

all of the old ways to be on the “cutting edge”. Along with the overthrowing

of anything that smacked of “academicism”, went the art of draftsmanship

— as if, knowing the basics of drawing — which have been with

us since the dawn of cave paintings — might somehow ‘taint’ one’s

artistic freedom to be oneself. If — as Olson avers and I endorse

— that drawing is “unrivaled in demonstrating the touch of the artist

and revealing insights into the creative process”, then I fear that we

have still to define an authentic “American” voice in the world of art.

Pierre Vase Male and Female Brambling (Fringilla montifringilla), ca. 1554-65 Watercolor, black ink, and white lead pigment over black chalk on three sheets of ivory paper, pieces and formerly mounted on an album page 11 x 123/8", irregular |

Perhaps,

when all is said and done, it is a bit presumptuous to even look for an

“American” voice in our art. America, after all, is only a little over

two-hundred years old. Some cultures have had thousands of years in developing

a distinct ‘handwriting’ from the basic drawing skills learned in pre-historic

times — to be obvious, one can readily distinguish, say, the work

of an ancient Egyptian artist from that of an ancient Mayan. America has

had no such germinating period. As Oscar Wilde once joked, “America is

the only country that went from primitivism to barbarism without ever

having passed through civilization.” He may have been joking at our expense

but there is a grain of truth in his observation. Over lunch with Françoise

Gilot some time back, I recall bemoaning the fact that we lack a cultural

base in the U.S., that many of our artists seem to have no direction.

She pointed out that it was her opinion that, unlike she and her European

colleagues, American artists were much more fortunate since, in her words,

“they had nothing to unlearn”.

Whatever stance you take, America has

been a “melting pot” from its very inception — as the list of artists

in this exhibition confirms — and continues to be to this very day.

Our ‘culture’ is, at bottom, a hodge-podge of contradictions. The philosopher

Jose Ortega y Gasset once described humans as being “shipwrecked” at birth.

‘Pure’ beings at their inception, they immediately grasp whatever flotsam

and jetsam is nearby in order to stay afloat in that particular part of

the ocean of life that they happen to find themselves born into. These

non-self ‘things’ — family, nation, language, customs, geography

— become attached but never truly are an integral part of the essential

being. Humans identify with what they cling to; some forget their true

selves and become only what they have managed to grasp onto. The

trick is to never lose sight of what we are — but this takes a lifetime

to discover. For nations, the process is surely longer. America is still

young, still grabbing at whatever flotsam and jetsam floats by. It adopts

as its “own” whatever trend appeals to the imagination of its current

generation. To whom can we point and say, “Now there — that’s

the result of a truly ‘American’ eye”? Almost by definition, then, to

be “American” is to be a member of a multi-cultured society, each artist

emerging on our soil bringing to his or her art the distilled aesthetic

souls of their ancestors. One can only hope that Ms Olson’s observation

is true that the art of drawing is making a comeback and there is indeed

a “trend” (pg. 31) toward making it once again a recognized part of fine

art — but I fear that it will take a much longer period of maturation

— if indeed such a thing comes to pass — before we truly arrive

at what we might call an “American” art with its own, distinctive signature.

The question, however, may be moot in any event with today’s “flat” society

of cyberspace that has effectively obliterated political and cultural

boundaries around the globe. Who knows? The idea of a national aesthetic

“voice” may someday be as ‘dead’ as are the ancient civilizations that

once gave them existence.

I found many gems in this show, some of

them stopping me dead in my tracks. I’ve already mentioned the sketchbook

of Joshua Rowley Watson. But you ought also take the time to savor Thomas

Cole’s “Study of Tree Trunks” (Cat. No. 61); the treasure-trove of drawings

by Asher B. Durand (pp.178ff in the Catalogue — The Society, incidentally,

has the largest collection of Durand’s work in the world!); James Carroll

Beckwith’s pencil sketches of John Singer Sargent; or John William Hill’s

“Bird’s Nest and Dog Roses, 1867” and “Dead Blue Jay, c. 1865”, his strikingly

realistic depiction of the fallen blue jay masterfully rivaling almost

any of the highly stylized birds found in Audubon’s famous portfolio (Cat.

Nos. 77 and 76, respectively). Whatever thread you choose to follow

in this provocatively stimulating show, I am sure you will have counted

your time well spent in viewing this impressive exhibit at the New-York

Historical Society.

*

“Drawn by New York: Six Centuries of Watercolors and Drawings at the New-York

Historical Society” (thru Jan 7): The New-York Historical Society, 170

Central Park West, NYC (212) 873-3400. A 450-page, fully-illustrated catalogue

accompanies the exhibition that, after closing, will travel to the Frances

Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY (Aug 14 thru

Nov 1, ’09) and to the Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati, OH (Nov 20 thru

Jan 17, ’10).