(845) 246-6944 ·

info@ArtTimesJournal.com

|

|

at the National Academy Museum

By RAYMOND J.

STEINER

ART TIMES October 2008

Co-curated

by members from three institutions — the National Academy Museum,

the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and the Columbus Museum of

Art, the three separate Museums have mounted a traveling exhibition which

begins in NYC (see below for schedule) — the full-color catalogue,

along with curator statements, features an essay by Thomas H. Garver,

the author of an earlier book on Tooker, George Tooker, Rizzoli

International Publications, Inc. 1987 (reviewed in our pages in our Jan/Feb

1988 Issue and since re-issued by Pomegranate Communications, Inc. in

1992 and Chameleon Books, Inc. in 2002). In both books, valiant efforts

are made to “pigeonhole” the work of George Tooker, but, as in the case

of most artists, such defining is difficult — and especially when

defining one that gives fair warning by stating outright, “we’re all complex”.

“Window VII”, 1963 egg tempera on gesso panel 24 1/8 x 21 1/8 in (61.3 x 53.7 cm) Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection 1992.168 |

George

Tooker was one among many of that generation of artists who, coming from

academic backgrounds, suddenly felt themselves caught up — if not

overwhelmed — by the onslaught of what many refer to as “modernism”.

The hardier ones, those more rooted in the concept of art being a “passed-down

craft” of skills —artists, for example, like Paul Cadmus, Jack Levine,

Isobel Bishop, Reginald Marsh, Will Barnet and, of course, George Tooker,

among others — never really buckled under to the pressure of embracing

innovation for its own sake or on its own terms. This, in spite of arguments

by many who, feeling the work of these artists was too important to sweep

under the rug of art history, contorted their “critiques” into facile

apologies claiming that — well — underneath the apparent figurative

realism — artists like Cadmus, Tooker, Bishop, or their like, were

really “closet modernists”, artists who “fitted in” all along.

This is not what I heard back in the early ‘80s from Isobel Bishop,

Bernarda Bryson Shahn, Paul Cadmus, and other figurative painters who

I was then meeting with and profiling for ART TIMES. They were

justly proud of their training, their knowledge of Renaissance techniques,

the virtuosity needed in expertly using materials — and all steeped

in a tradition of humanism that they felt an integral part of and indebted

to. All were fairly candid — and vocal — about their unhappiness

with being shunted aside by what they considered less talented if more

publicly vaunted up-comers. Over lunch one day in the Village, Jack Levine

— who could grow incensed by any mention of the “abstract expressionists”

— put it rather bluntly when he said, “I never said that Jackson

Pollock couldn’t draw his hand — I said he couldn’t even trace

it!”

Less

explosive but as intellectually opposed to what was happening to their

craft, Paul Cadmus — serious, reserved, dignified, almost patrician

in his measured judgments and responses to my questions — gave little

quarter to “modernist” tendencies. He once referred to a drawing of a

woman he’d done as a child as his “DeKooning Period”. He kept it hanging

in his living-room/studio.

“Lunch”, 1964 egg tempera on gesso panel 20 x 26 in. (50.8 x 66 cm) Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio: museum Purchase, Derby Fund, from the Philip J. & Suzanne Schiller Collection of American Social Commentary Art 1930-1970 |

Jack

Levine had recommended Cadmus to be on my short list of candidates for

inclusion in our publication so I’d profiled him in May of 1984 for ART

TIMES. Less than two years out on the stands at the time, we were

already dedicated to what we called the “long view”, ignoring much of

what was being called “cutting edge” since so many arts publications were

already hot on the trail of every newcomer on the scene. Like Levine,

Cadmus became a friend as well as a subject, and on a subsequent visit

to his home/studio in Weston, Connecticut, the subject of the “artworld”

of course came up. However, he rarely spoke about his work directly, knowing,

as most good artists are aware, that art — if it is genuine art

— must speak for itself and needs — indeed, can suffer

no linguistic translation. It was certainly not that he was reticent.

Literate and worldly, Cadmus was always a pleasurable and edifying conversationalist.

It was simply that he, like many of his colleagues, had little respect

for the artist who sought publicity, who eagerly invited journalists and

talked about their art. “They are famous,” he once said, “for being famous.”

When

I asked Cadmus — as I had asked Levine — what artists I ought

to write about, there was no hesitation in his response: “George Tooker,”

he promptly told me.

This

was about twenty years ago, and I regret that the meeting between Tooker

and me never took place. I no longer recall why — Cadmus had contacted

Tooker and set up the possibility — but the arrangements were never

made — either Tooker's or my schedule prevented my taking the trip

to Vermont, and for whatever reasons that followed, we never personally

came face to face. A pity, since it is my habit never to rely on the words

of others — especially when it comes to artists. No two are alike

— can never be alike — and when it came to the old-schoolers

it was important to see them on their own turf, to know them on their

own terms, and not through the eyes of revisionists trying to claim them

as “wannbe modernists” — if only to make them more palatable (and

saleable) to a less-informed art market/public. I recall Cadmus telling

me that Tooker was jealous of his privacy — an observation borne

out by a quote of Tooker’s that Garver uses to open his chapter “On the

Art of George Tooker”, namely, “Painting is a very isolated occupation”.

Subway, 1950, egg tempera on composition board, 18 1/8 x 36 1/8 in. (46 x 91.8 cm) Whitney Museum of American Art, NY Purchase, with funds from the Juliana Force Purchase Award |

In

the long run, however, it is always the art and not the artist (or critic/historian)

that speaks the loudest — and, as noted above, we have some sixty-six

works on which to attempt some insight into the aesthetic vision of George

Tooker…so perhaps there was never a necessity to make that trip up to

Vermont, after all.

Setting

aside for a moment Tooker’s subject matter, the merest of glances at either

his graphic work or his egg tempera paintings — the medium alone

speaking volumes about the man and the artist — indicates a consummate

perfectionist. He, like his friend Paul Cadmus, takes his time for a work

to germinate, develop, and evolve — Cadmus, in fact, only did a

handful of works each year. A more studied look might then reveal his

sense of composition, color, and chiaroscuro — something he seems

to have imbibed from a careful study of both Pre- and Full-Renaissance

masters. It is when we take the time for an in-depth visual tour of Tooker’s

work, however, that we begin to see just how “complex” he is. Whatever

Tooker is visually conveying (and the opinions are, as they must be, varied),

his work seems “of a piece”, a consistent world vision that, at bottom,

is almost universally disconcerting. If his technique “pleases”, his subject

matter seems consistently ominous. Interpretation of what he is “saying”

depends, of course, on the range and depth of the onlooker — mine

as well as yours — all such interpretations, perhaps, “valid” since

they reflect our genuine responses, but none definitive. Nor can such

interpretations ever be so. In Tooker’s own words (again taken from the

accompanying catalogue in the beginning of Marshall N. Price’s essay,

“From Anxiety to Agape: George Tooker and the Human Condition”) “I believe

Art, as painting, is communication of thought by means of design, form,

and color…” — in short, only as art and not as words.

The only “real” interpretation of a Tooker painting would (might)

be another painting of whatever Tooker is really communicating

by another artist…”all else is commentary”.

All of which is to say — go see this retrospective for yourself.

Whatever you come away with — though it may say more about you than

about George Tooker — you will have immeasurably added to your appreciation

and ken of just what genuine art can do.

I

laud the National Academy Museum, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine

Arts, and the Columbus Museum of Art, along with their curators and author

Thomas H. Garver, for sharing with us this most enigmatic of today’s masters.

*George

Tooker by Robert Cozzolino, Marshall N. Price and M. Melissa Wolfe.

Merrell Publishers Ltd. 2008, London and New York, pg. 31.

**

“George Tooker: A Retrospective” Oct 2—Jan 4, ’09: National Academy

Museum, 1083 Fifth Ave., NYC (212-369-4880. The exhibition will then travel

to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia (Jan 30—Apr

5, ‘09) and the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio (May 1—Sep 6, ;09).

A full-color catalogue is available.

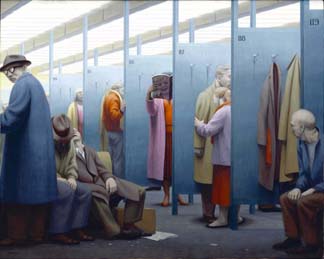

Waiting

Room, 1957, egg tempera on wood, 24 x 30 in.

Waiting

Room, 1957, egg tempera on wood, 24 x 30 in.