Share |

Art Review: Patrick Heron: The Colour Magician

By Ina Cole

ART TIMES September/ October 2012

'I think this world is magical. Colour, form, space, relationships ‒ these elevate life. They energise. They elevate my whole consciousness...I think art heightens the potential of the actual' ‒ Patrick Heron (The Colour of Colour, 1994-5).

In 1956 Patrick Heron (1920-99) left London for Zennor, St Ives, and moved into Eagle’s Nest; a house perched high on a cliff edge that had been familiar to him since childhood. Heron was well established as a leading critic and painter in London, and this move marked the beginning of a period when St Ives could reasonably claim to be a world centre for modernist innovation; a place that created an instinctual connection between man and nature. Throughout history particular landscapes have been immensely influential in their relationship to certain periods of art, and St Ives acted as a magnet precisely because twentieth-century abstract and semi-abstract painting possessed fundamental rhythmic propensities with this kind of terrain. Of course these developments did not occur without recourse to the wider world: at the time British artists were looking to the US for stimulus and Heron was particularly conscious of this two-way influence. The dominance of an American narrative of modernism had channelled much of the critical debate since the Second World War, and its criteria directed many qualitative judgements of British modernism. However, even though there were direct cross-influences between Britain and the US, the roots of the Americans lay in European Symbolism and Expressionism, whereas the British painters were primarily affiliated to the English landscape tradition.

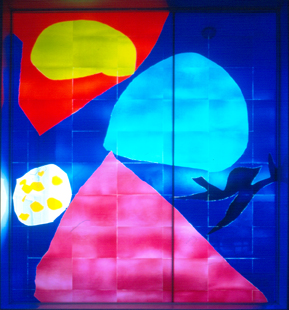

Patrick Heron, Window for Tate St Ives (1992 – 1993); coloured glass 460 x 420 cm; picture credit: Tate St Ives Patrick Heron, Window for Tate St Ives (1992 – 1993); coloured glass 460 x 420 cm; picture credit: Tate St Ives |

The work of the Abstract Expressionists, centred in New York from the 1940s to the early 1960s, represented a period that directly paralleled the early achievements of Heron and his St Ives contemporaries. Heron had stronger contacts with the US than any other London artist of his generation, and through his writings in the New English Weekly; The Listener; New Statesman; Arts (New York); and The Guardian, brought a number of St Ives artists to the attention of a transatlantic audience. He had the ability, partly because he was a painter himself, to understand the complexities of a work and convey this with great eloquence. On meeting Heron, the writer David Lewis wrote, ‘Patrick Heron is perhaps the most literate painter I have ever met. Yet that in itself is misleading. When I met him in London in 1950 he was better known as a critic than as an artist. Yet there was nothing literary about his painting. Quite the reverse. His art explored a progression of visual experiences which informed and sharpened his literary sensibilities, to a point that his capacity to enter into the work of the painters and sculptors he wrote about was, in my view, unmatched in English criticism since Ruskin' (St Ives 1939-64, 1985). As a consequence of the interest generated by this literary exposure, Heron and his contemporaries held around fourteen one-man exhibitions in New York in the 1950s and 1960s, which has to be seen as an indication of the international significance achieved by this generation.

The specific local conditions in which a work is produced plays an important role in the understanding of the culturally divergent forms of modernism, as it is only the interplay between social, aesthetic and individual forces that can offer a coherent interpretation of art practise grounded in its historical context. In relation to this, the mid to late 1950s were a particularly significant period in the evolution of Heron’s career; a time when he began to create abstract works using intense colour and freely applied brushwork. Many of these works reflect the influence of the colours, shapes and textures found in his garden, and foliage is often represented by a series of overlapping marks on canvas. These paintings are unequivocally celebratory, relying heavily on pure visual sensation, thereby offering the viewer an immersive and liberating experience. At this time, Heron's work progressed through a series of stages that separated it from its figurative associations and linked it firmly to the principles of colour: the stripe paintings, for instance, which are seen to be analogous to light, sky, sea and horizon, have been associated with the limitless expanse of landscape surrounding Eagle’s Nest, but can also be regarded purely as colour experiments. However, Heron did not embark on this in isolation: in the 1950s artists in New York such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman also conceived their compositions not as a process of relating separate planes in depth, but as the establishment of a continuous surface capable of sustaining the same level of intensity from edge to edge and from top to bottom.

In the 1960s and 1970s Heron's paintings became totally non-figurative, based on geometric forms, freely drawn and increasingly irregular, often set within sizzling colour juxtapositions. Heron wrote in the 1960s that, 'Colour is both the subject and the means, the form and the content, the image and the meaning in my painting today' (Painter as Critic, 1998). He had a way of drawing onto canvas directly from the tube, introducing colour into line, so that space in his paintings was not merely a function of drawing but was syncopated by colour, moving it back and forth, bringing a new freedom. This technique was one he continued to use to great effect in the garden paintings of the 1980s and 1990s, but substantial changes in his approach were evident in these later works, which became more linear with a highly calligraphic quality. Whereas the 1950s paintings highlighted surfaces animated with colour, his later works have a brilliant clarity, with an emphasis on the outlines of the forms. Heron grew plants in greenhouses at Eagle’s Nest and his garden was central to his existence there; a subject he returned to time and time again. On this he wrote that, 'The majority of the garden paintings were stimulated by the wonderfully exuberant froth of the numerous camellias and azaleas in flower all over the garden at Eagle’s Nest when we arrived there to live...they were a response to the actual petals, whether fleshy or papery, of the flowers themselves, as well as to their small new leaves (azaleas) and the large glossy leaves (camellias) on the trees ‒ all of which hung, before one's eyes, like bead curtains punctuating deep space, as one gazed right into these trees and bushes' (St Ives 1939-64, 1985).

Intoxicating colour, form, and meandering line remained amongst Heron’s guiding principles throughout his career. His sense of freedom, both in terms of human spirit and the development of the work were clearly articulated, 'I believe that art is autonomous...I do not mean literally, that painting and sculpture have no traceable connection with all the other activities which go to make up human life on this planet. But, this connection can only be traced after the event, by the critic. It cannot be planned in advance, by the painter, without involving the loss of his freedom’. As far as Heron was concerned the artist should deliver the goods and leave evaluation to others, 'Who would expect Einstein to modify his intuitive creative thought because he had become aware that he would be unable to state his discovery in terms accessible to the majority' (Painter as Critic, 1998). Most importantly, the work of Heron and his St Ives contemporaries brought abstraction into free play with landscape elements, and this kind of emotional abstraction, or hyper-sensitivity to the characteristics of a location, resulted in a major art form of great originality, which made its own powerful contribution nationally and internationally. In British art it added the dimension of the wilder and more remote outdoors, offering significant new forms of linking man with the landscape; internationally it shared fully in the liberating ideas that radically changed the artistic climate of New York in the 1950s and early 1960s.

(Patrick Heron’s work can be seen at Tate Britain; Tate St Ives, UK; and Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven, CT, US. His work is also held in the following US collections: Brooklyn Museum; Albright-Knox Art Gallery, NY; and Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, MA.)