(845) 246-6944

· info@ArtTimesJournal.com

Rules

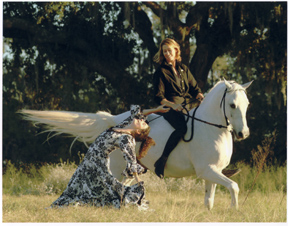

of Engagement: Dancers and A Horse

By Dawn Lille

|

ART

TIMES December, 2005

Horses and dance?

Why not? Equestrian ballets, which were derived from medieval tournaments

and involved hundreds of horses and riders moving in elaborate formations,

date back to the early Renaissance. The horses and their riders/dancers

in the Ringling Bros. Circus, and the Zingaro Company of Spain also come

to mind, as well as George Balanchineís choreography for fifty elephants

and fifty beautiful girls.

But,

as JoAnna Mendl Shaw, Artistic Director of The Equus Projects, rushes

to point out, all of these require human control over an animal. These animals were rigidly controlled

by people. Rules of Engagement, an interdisciplinary and interspecies performance she recently presented

at the Claremont Riding

Academy, is about the interaction of horse and dancer, each trying to

understand and feed off the other in an atmosphere of trust. Her artistic

collaborator here was Janet Biggs, a visual artist who works in painting,

sculpture and multiple channel installations. The company consists of

three dancers, an equestrian and a horse, Navajo Medicine Man (Navi),

an eighteen-year-old appaloosa gelding.

The

riding area of the stable was the site-specific venue for this production.

The audience, sitting in bleachers on one side, saw two large screens

set at slight diagonals to each other and big enough so that they effectively

blocked anything behind them. The dancing took place in front of and between

the screens; Navi, with his rider Blair Greismayer, walked endlessly in

circles and ovals, sometimes going between the screens and dangerously

near the moving dancers. The

first thing the audience saw was the double image of a horse walking.

This then focused just on the legs and melded into a horse running in

place on a treadmill, but facing itself via the two screens. Suddenly

there was an awareness of the three dancers. One, MaryAlice White, moved

in what resembled satyr-like upper body gestures. Then Blake Pearson and

Gina Paolillo started to travel slowly and simply into each otherís space.

When Navi appeared they acknowledge him in movement and included him in

their continued exploration.

Broken

down, the overall production had three elements: the horse and his partner/rider,

the dancers and the video. The first two developed an ongoing movement

conversation, with the rider allowing her horse as much freedom as possible.

The last included additional images of deer, an owl, an eagle, icebergs,

waterfalls and bodies under water. As the one hour work progressed the

dancers and Navi interacted more and more, the videos seemed to make the

viewer switch gears and enter another thought process, and the dance gestures

and designs became more complicated spatially, dynamically and rhythmically.

The score by Steve White was supportive without being overwhelming

and the lighting by Philip Sandstrom was amazing, given the space. The

piece, which is ultimately about issues of domination and sexuality, has

a history and philosophy behind it.

Shaw

started this work in 1997 when she was commissioned by Mt. Holyoke College

to make a piece for the Five College Dance Department. Upon discovering

they had an amazing equestrian program, she decided to put the two together.

A former competitive skier, she considers herself an athlete as much as

a dancer and regards dancers as consummate athletes. She ended up creating

a trilogy at Holyoke that used ten horses and fifty humans. What amazed

her was the realization that the horses followed the dancers. She wanted

to continue this work and found three riders and three dances. They gave

their first concert in 1999 and spent several summers in residence in

Vermont, where she created a full evening work for the Flynn Center for

the Performing Arts.

The

process of training both the dancers and the horses, although more the

dancers, has been a long one that is still evolving. They have spent countless

hours improvising. Horses are herd animals and the dancers learned to

work as if they were another horse, shaping the space between bodies.

The animals do this instinctively and they also remember the choreography.

So in order to keep the process ongoing, especially in performance, the

dancers must work to be constantly interesting to their animal partners.

This is where improvisation becomes almost a necessity.

There

were two wonderful examples of it in Rules, both horse/human duets.

In one Gina Paolillo was talking in Italian while she and Navi moved together,

using their body contact to propel them through space. In the other Blake

Pearson and Navi were head to head, with the dancer causing the horse

to retreat at one point. Shaw says that horses do not understand spoken

commands, only physical ones. Hence Ginaís section was about the quality

of her body next to Naviís and Blakeís was ultimately about the strength

level of his touch.

The

dancers have spent several weeks at a time working ten hours a day with

cowboy Pat Parelli and his wife Linda at their ranches in Colorado and

Florida. Here they have learned partnership training and how to relate

to a horse.

When

asked about the qualities she looks for in dancers and horses, Shaw says

her dancers must be grounded and possess an understanding of weight and

space. They need hamstring strength and a sense of the pelvis. This work

requires a strong technique and a lack of ego. The horses must be loved

and cared for. She cannot work with a frightened or abused animal. A horse

listens physically, engages all the senses and operates in three-dimensional

space. The dancer must learn to do the same. The final result requires

a level of respect and humility based on time and knowledge.

Rules

of Engagement explored risk taking, power, relationships and the ability

to be violent on both the human and the animal level, as implied by the

video of the eagle. The horse, however, is not a violent creature and

does not initiate violence.

Shaw

says the old hierarchy between choreographer and dancers is minimized

when working with a choreographer, a dancer, a rider and a horse. This

was a collaboration of many, a process and an inquiry. It cannot be judged

in comparison with other dance works. But it can certainly stimulate thought

and pose questions about human behavior and the possibilities inherent

in an art form.