(845) 246-6944

· info@ArtTimesJournal.com

Shakespeare

on Broadway 3

By

FRANK BEHRENS

ART TIMES

March 2006

Whenever I give

a talk that includes the musicals of the 1950s, there is always a laugh

when I mention that the original title of “West Side Story” was “East

Side Story.” Well, it’s true. In 1949, Leonard Bernstein and Arthur

Laurents were asked by Jerome Robbins to collaborate on a musical based

on “Romeo and Juliet.” But instead of feuding families, there would

be feuding religions as a Jewish boy falls in love with a Catholic girl

despite the pressures put upon them by their peers.

The

idea never came to fruition, but it stuck in Bernstein’s mind. However,

for several reasons, he decided to change the religious slant to an

ethnic one and moved the action from the East to the West Side of Manhattan.

Bernstein explained that the Jewish-Catholic gang problems had died

down somewhat, whereas the influx of Puerto Rican families and the culture

clashes with the “older” inhabitants were in the news. I personally

have always suspected that he made the change because Puerto Rican music

provides much better dance sequences than does liturgical music.

Although

the playbills and scores show that the lyrics are those of Stephen Sondheim,

insiders have always said that some of the songs are entirely the work

of Bernstein. But until some evidence is unearthed, one can never tell

who wrote what.

On

the whole, the Romeo and Juliet story is fairly faithfully handled,

what with the rival gangs being the perfect updated version of the Montague

and Capulet street brawlers. Even the bawdy humor of the servants that

opens up the Shakespeare play is preserved in the mocking “Officer Krupke”

sequence.

One

of the major elements of the Bernstein creation is the emphasis on dance.

So the Capulet ball becomes the dance at the gym; and the now graceful,

now dynamic dance numbers nearly compensate for a good deal of the Shakespearean

poetry that is lost in this transposition of the action to Manhattan

of the 50s.

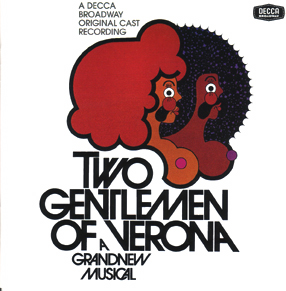

Passing

on to 1971, we have the Joseph Papp production of “Two Gentlemen of

Verona.” This is certainly one of Shakespeare’s earlier comedies and

not a very well known one at that; so Papp felt he could stick with

the plot as given, but set it in a sort of timeless zone in which costumes

from all periods could be used. And, of course, set it all to rock music.

Now

in my mind, this is a most serious departure from the “feel” of the

original. The Shakespeare play is a spoof on the exaggerated importance

of fine speaking and witty remarks. Any good production will positively

drip with elegance as the young lovers—Valentine and Proteus (guess

which one is the unreliable one from the names alone) and the much sought

after Julia and her friend Silvia—go through all the superficialities

that high society demanded back then. Somehow—and I might get

arguments—rock music simply cannot by its very nature carry that

essence.

But

who can argue with success? The play ran for 627 performances, but never

enjoyed a film version or continuing revivals as did “West Side Story.”

The

same problems crop up with filming Shakespeare in updated surroundings.

At the very least, “thee” and “thou” ring false when “Twelfth Night”

(say) is presented in Victorian dress, not to mention the swords. I

cannot bring myself to watch the “Titus” film which is set in a nightmare

Rome that includes loud speakers and motorcycles and in which no one

can create a credible character in this incredible world.

On

the other hand, neither Rodgers nor Hart really expected an audience

to believe that 1940s tunes were being sung by characters in the ancient

world of Ephesus. Then again, “Comedy of Errors” is particular devoid

of beautifully poetic lines. That is why (for me) “The Boys from Syracuse”

succeeds where Papp’s “Two Gentlemen of Verona” fails. It is not because

the score of “Two Gentlemen” is inferior to that of “The Boys”—which

it most certainly is—but that it conflicts with the essence of

the play whereas the Rodgers score does not.