Hear the Song, Read the Book -2

By FRANK BEHRENS

ART TIMES Nov/ Dec 2009

|

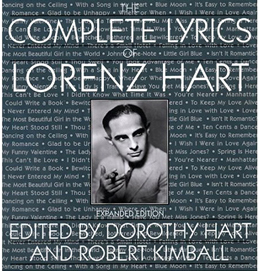

In the last issue, I took a look at how following in print the collected lyrics of a few song writers could increase our appreciation of their talent. Larry Hart is a particularly good lyricist to study, because his versatility in rhyming where no man has rhymed before (sorry, Capt. Kirk) is his most outstanding characteristic.

But so is his cynicism. Not many lyricists would write that “This can’t be love because I feel so well” or “Falling in love with love is falling for make believe” or “Kiss me and say goodbye, that’s love.” I think an analyst would have a field day with his view of the tender passion. But those aware of his bitterness over his short body topped by a normal sized head and possibly over his sexual preferences can understand his attitude towards love. They can also understand lines like “Though your figure’s less than Greek, though your chin’s a little weak” in the aptly titled song “My funny Valentine.” I think I enjoy reading his lyrics almost as much as I do hearing them sung.

However, I have considered Hart in past essays and had best pass on to Ira Gershwin. George’s brother did not try for tricky rhymes but for slightly different ways of expressing ideas that had long since become clichés with other lyric writers. His own reminiscences and analyses of many of his songs are contained in his book (and I give the full title) “Lyrics on Several Occasions: A Selection of Stage & Screen Lyrics Written for Sundry Situations; and Now Arranged in Arbitrary Categories. To Which Have Been Added Many Informative Annotations & Disquisitions on Their Why & Wherefore, Their Whom-for, Their How; and Matters Associative” (Limelight Editions).

One of his few bitter comments is directed at those singers who take “’S Wonderful” and supply the missing “it,” thereby ruining the effect entirely. He also says that his greatest challenge came in “Lady Be Good” when George gave him a melody that was so syncopated as to leave Ira at a loss for lyrics that would fit. But the very problem provided the answer. And so the first line of the refrain became “Fascinating rhythm” and the rest flowed easily from there.

Happily, Knopf also has “The Complete Lyrics of Ira Gershwin” in its catalogue. Here one can appreciate every lyric from his first recorded try in 1917, “You may throw all the rice you desire” to those he wrote in 1964 for the film “Kiss Me, Stupid.” Without being self-consciously novel—Hart and Porter do tend to show off their cleverness—he gives his lyrics a more colloquial sound and a generally optimistic tone. In fact, one of his really downbeat songs, “But not for me,” could easily be taken for a Hart lyric were it not for lines that end with a pun like “The climax of the plot should be the marriage knot, but there’s no knot for me”.

“Noel Coward: the Complete Lyrics” is published by The Overlook Press (1998) and uses the identical format to that of the Knopf editions. Coward comes closest to Gilbert in his use of satire, light and keen. His most popular fun song is “Mad dogs and Englishmen” who go out in the midday sun, which laughs at the Brit in the far flung parts of the Empire. His most popular sexy song is “Let’s do it,” which boasts of music by Cole Porter and which is performed to perfection by Coward himself on several recordings. Interestingly, he nearly speaks the lyrics, making it sound like a poetry reading more than a song recital, which is my very point in these essays.

His nastiest lyrics must be “Don’t let’s be beastly to the Germans” (1943) in which he devastates any post-war pleas for “forgive and forget.” I point out only two lines to give the flavor of this song: “Let’s help the dirty swine again/To occupy the Rhine again”; “Let’s let them feel they’re swell again and bomb us all to hell again.”

For the most part, however, reading Coward’s lyrics is like reading the Jeeves novels of that other lyricist, P. G. Wodehouse. They conjure up an Oscar Wildean world of useless but amiable upper class twits expressing themselves with the utmost sophistication and laughing at themselves without realizing it. Even non-satirical songs like “Somewhere I’ll find you” are aimed at an audience a little more sophisticated those of Irving Berlin and Ira Gershwin.

I would like to pursue this line of thought in other essays with other lyricists. However, I still recommend reading lyrics divorced from the melodies as a source of innocent merriment or as an insight into the personalities of the authors and the times in which they lived.

fbehrens@ne.rr.com