(845) 246-6944 ·

info@ArtTimesJournal.com

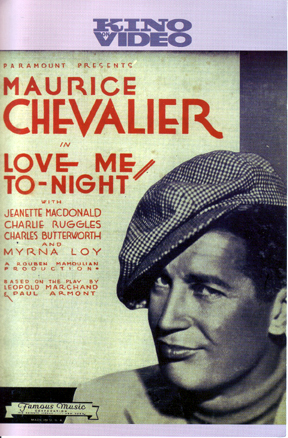

Love Me Tonight: An Appreciation of a Great Almost Forgotten Musical Film

|

By

FRANK BEHRENS

ART TIMES October 2007

Most

of the earlier movie musicals

were concerned with a troupe putting on a musical. The best of them

is “42nd Street,” many of the others a pale imitation of that wonderful

work. A good many other film musicals are simply fair or not at all

faithful transcriptions of a stage show to the screen.

However, now and then there is a musical written specifically

for the screen that really works.

The Astaire-Rogers films had wonderful

music and exquisite dancing, while the plots were lame, predictable

and juvenile. A rare treat like “Seven Brides for Seven Brothers” was

a welcome exception in which every element just worked! In this essay,

I want to turn my readers’ attention to an even more exceptional musical

film from 1932 called “Love Me Tonight.”

Designed as a vehicle for Maurice

Chevalier and Jeanette MacDonald, it boasts a fabulous score by Richard

Rodgers and Larry Hart. The slim plot, alas, depends on the very wealthy

MacDonald mistaking the lowly tailor Chevalier for an aristocrat when

he comes to her chateau to be paid for his work by Charlie Ruggles.

So much for the story.

The film opens as does no other film

musical in my recollection. In silence. A quiet street

in Paris at sunup. Clock bells chime. A worker comes out to pound with

a rhythmic beat a hole in the road. He is joined by a man snoring, a

woman with a broom, some chimneys spouting smoke, a crying baby, the

metal door guard to a shop being rolled up, a blanket being snapped

to be aired out, two cobblers at their laths, a knife grinder, a woman

beating a carpet, some car horns—each with a contrasting beat—until

a young girl puts on a phonograph record to bring some melody onto the

scene. This provides the background for Chevalier’s first number, “The

Song of Paree,” which carries him from his flat to his shop.

After some rhythmic and rhymed dialogue

with a customer, Chevalier begins “Isn’t It Romantic?” with some male-chauvinist

lyrics (that were changed when the song became a single). The customer

leaves the shop singing part of the lyrics and is overheard by a taxi

driver, who hums the song in the presence of a composer who takes the

cab to the station. Giving the song new lyrics, the composer is overheard

by a troupe of soldiers, who adopt it as a marching song, which is overheard

by a convenient gypsy violinist, who plays a melancholy version to his

people. This is overheard by MacDonald on her balcony and she sings

it with yet newer lyrics—thereby establishing her connection with

the male love-interest far before they meet.

Just before they do meet, she sings

a “throwaway” song to her horse, “Lover,” which became a perennial hit

(much to Rodgers and Hart’s surprise). When they finally meet, Chevalier

calls her Mimi for the sole purpose of introducing another hit song

of the same name. When the tailor is revealed as a non-noble, “The Son-of-a-Gun

is Nothing But a Tailor” is sung first by all the main characters (including

the venerable C. Aubrey Smith in his only singing moment on film) and

then by the downstairs staff.

In short, the team, along with director

Rouben Mamoulian, had found a solution for the musical-comedy question.

How does a musical number advance the plot and at the same time hold

the viewer’s interest in a dark movie house?

(The biggest laugh, by the way, is

a non-musical one. When her sister is ill, the love-starved Myrna Loy

is asked, “Can you go for a doctor?” She brightens up and says, “Certainly.

Bring him right in.”)

In his autobiography, “Musical Stages,”

Rodgers writes that he, Hart and Mamoulian, were “convinced that a musical

film should be created in musical terms—that dialogue, song and

scoring should all be integrated as closely as possible so that the

final product would have the unity of style and design.” They also wanted

“not only moving the camera and the performers, but having the entire

scene move” during musical numbers just as it does in a dialogue

scene. The fact that not every song quite achieves this goal is unimportant

since half of the songs do. (Wouldn’t Wagner have approved?)

Many film versions of stage musicals

overdo this concept by having the singers suddenly shift locations without

missing a beat of the music. This is merely film gimmickry and not what

Rodgers et al. had in mind at all by “movement.”

Now and then, the Turner Classic

Movies cable channel will show this film; and it is available on the

Kino Video label. Well worth seeing.

And I would appreciate nominations

from my readers for other musicals made for film that have high merit.