(845) 246-6944

· info@ArtTimesJournal.com

The Riddle of the 3 Riddles in “Turandot”

|

By

FRANK BEHRENS

ART TIMES September 2007

The

plot of Puccini’s last opera

“Turandot” hinges on the nameless suitor answering three riddles. Readers

familiar with myth and folklore will instantly recognize this as an

element common to many tales.

The

suitor in “Turandot” is faced with having to answer three abstract riddles,

the answers to which are “Hope,” “Blood,” and “Turandot.” (One wonders

if each suitor got the same three, considering that they are read out

loud and word must have gotten around if they were unchanged through

the years!) If he wins, he gets the Princess; if he loses, he loses

his head. Since Turandot herself is the cause of many deaths in the

past, one should keep her association with Death in mind as we proceed

in this essay.

In

Wagner’s “Siegfried,” Wotan in his guise as The Wanderer, plays (as

Anna Russell puts it in her spoof of the Ring Cycle) 20 Questions with

Mime. The dwarf wages his head (cf. the wager in “Turandot”) that he

can ask his guest three questions and then answer whatever three the

guest proposes. Mime’s questions are easily answered by Wotan, and Wotan’s

first two questions are easily answered by Mime. The last question,

however, “Who will forge the sword?” puts Mime in great jeopardy. Again,

the last answer concerns an instrument of death—and again the

contestant’s head is at stake.

In

Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice,” Bassanio is confronted with

three caskets: gold, silver, lead. A portrait of his beloved Portia

is in one. The audience knows which casket is the right one, because

it has seen two other suitors choose the wrong ones. What is at stake

here is Bassanio’s love and his need for money, both of which Portia

is willing to satisfy—and indeed she has a song sung to Bassanio

before he chooses in which most of the end words rhyme with “lead.”

Consider,

now. Lead is associated with bullets and coffins, and is found deep

in the earth. Again, Death lies in the third riddle.

In

the folk tale, Goldilocks enters the house of the Three Bears. From

the best bowl of porridge to the best bed, the first and second choices

are too extreme while the third is always “just right.” When the anthropomorphic

family returns, the little human barely escapes with her life—and

a record of breaking and entering, I suppose.

In

myth, the shepherd Paris (or in some versions, Alexander) is suddenly

faced with three naked goddesses, each of whom bribes him to award her

the Golden Apple. Hera offers him the rule of Europe and Asia, Athena

offers him the power to lead Troy to victory against the Greeks, Aphrodite

offers him the fairest woman in the world. Since the latter is Helen

of Sparta and her departure to Troy with Paris leads to the death of

countless soldiers and citizens, that third choice seems yet again one

of certain death.

One

step back again to very early myth. The Moon appears in three phases.

When full, it is Selina, Queen of Heaven. When it is in the shape of

a bow, it is Artemis, the Huntress Queen of the Earth. When it is the

New Moon (that is, no moon at all), it is black Hecate, Queen of the

Underworld. And there we are again!

Freud

considered this theme and concluded that humans will forever harbor

a Death Wish, making choices that lead thereto. I see it from a different

point of view. The very essence of three-ness is that three points form

a triangle. Consider that nearly every comic opera plot concerns two

characters of one sex in love with a third party of the other. In “Marriage

of Figaro” there is the Figaro-Susanna-Count triangle; in “Oklahoma!”

there is the Curly-Laurey-Judd triangle; in “The Mikado” we have Nanki

Poo-Yum Yum-Ko Ko!

If

we consider one of the males to be Thesis and the other Antithesis,

there can be no Synthesis (i.e., a Happy Ending) unless the undesirable

suitor bows out willingly or otherwise. This is the one of the great

elements of comedy.

In

tragic operas, however, that Synthesis can be brought about only in

Death. So Aida and Radames can be united only in the tomb while Amneris

curses the priests from above. Violetta and Mimi must both die of consumption

because Life with the Beloved has proven impossible. Both Tannhauser

and his Elizabeth must die to be united (one supposes) in a better world.

Going

full cycle, then, back to “Turandot,” her first kiss from a man suddenly

brings her over to his way of looking at things and the opera ends happily

(if one ignores the death of little Liu, the only really sympathetic

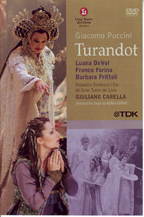

character in this tale). And yet, a recent production of this opera

(available on a DVD) takes a chance and has Turandot stab herself at

the last moment, even as the chorus is singing about how wonderful life

will be in Peking. Personally, I think the tenor doesn’t know how lucky

he is!