(845) 246-6944

· info@ArtTimesJournal.com

|

Dancing in Verona

By

FRANK BEHRENS

ART

TIMES June 200

Having already considered

Shakespeare in opera and Shakespeare in Broadway musicals, I want to

consider this month what might be the most successful translation of

one of his plays into a ballet.

By the very nature of things, Shakespeare as ballet is pure

nonsense. How could the most gifted poet in the English-speaking world

survive the sea change into wordless dance? If the answer is “No way,”

then we might as well stop here. But if the question becomes, “How could

the spirit of the original survive as dance?” then we have a twofold

answer.

Then, of course, we have the second element: the music. If

one sets (say) “Titus Andronicus” with all its nightmarish aspects to

an electronic 1960-ish horror film score, it just might work on stage.

I would, however, feel disinclined to play a recording of the score

alone, thank you very much. But such a score would be as out of synch

with the story of “As You Like It” as setting that play in modern costumes

would be out of synch with the speech and world view of the plot and

characters.

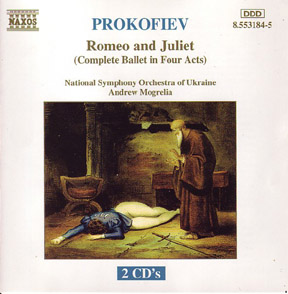

In my mind, the most successful transfer of a Shakespeare

play to the ballet stage is Prokofiev’s “Romeo and Juliet.” With the

exception of a passage that one finds in his Symphony No. 1, “The Classical,”

only some of the Prokofiev score sounds like the music of Renaissance

Italy, the rest more “Soviet” than Medici or even Elizabethan.

For example, the wealthy Capulets are shown to be arrogant

capitalists and their music is ponderous and self-important. The fight

music is filled with the sound of percussion and brass under the swirling

of the strings, leading to the heavy death music as Mercutio falls dead

and the Duke enters to stop the fray.

The love pas de deux that makes up the Balcony Scene is in

the neo-romantic style and must be compared with Berlioz’ setting of

the same scene in his choral symphony

“Romeo et Julette.” The part of the ballet score called “the

young Juliet” is the perfect evocation of a girl feeling her first impressions

of “what it means to be a woman” in her society; but the music grows

up with the character, and Juliet’s music is quite different after the

love duet.

Unlike the opera of Gounod or the symphony of Berlioz, the

ballet cannot give Mercutio his Queen Mab speech. However, the clown

in him is movingly depicted by the halting “wounded” music to show his

actions after he is stabbed by Tybalt under Romeo’s arm. Yes, perhaps

Prokofiev could have let him DANCE the Queen Mab speech. However, alas,

music can never be that specific and such verbal sequences simply cannot

translate into dance.

Charles Gounod was going to share a problem with Berlioz

in the former’s opera “Romeo et Juliette” concerning the death scene.

In the Shakespeare original, Juliet wakes after Romeo dies from the

poison, speaks some lines, and then stabs herself. Fine for Shakespeare,

not so fine for a ballet in which the couple are expected to have a

pas de deux, if only a moribund one, before the curtain. However pressured

to do just that, Prokofiev held out for the Shakespearean ending and

won. Gounod, however, does give them a brief duet.

The book “101 Stories of the Great Ballets” by George Balanchine

and Francis Mason (Anchor Books, 1989) gives the scenarios and backgrounds

to several other balletic treatments of this ancient tale. While there

are about a half dozen videos of the Prokofiev treatment, I cannot find

any of the others.

The version choreographed by Anthony Tudor in 1943 uses the

music of Delius. This is appropriate for at least the one reason that

Delius composed an opera called “A Village Romeo and Juliet,” from which

the entr’acte “The Walk to Paradise Garden” is often played at “pops”

concerts. Do any of my readers know of a video of the Tudor treatment?