|

The Right Musical at the Right Time

By

FRANK BEHRENS

ART TIMES May 2008

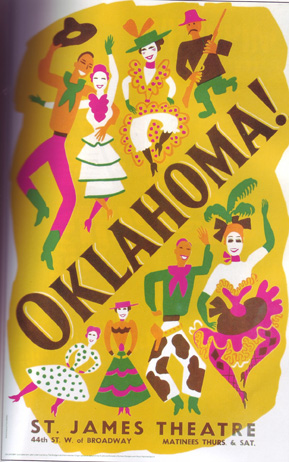

Consider. “Oklahoma!”

opened in March 1943. “Remember Pearl Harbor” was still a rallying cry

and young men were dying for a cause that was clear and an enemy that

was identifiable. Hollywood was churning out propaganda films in which

Robert Taylor was gunning down troops of Japanese and every regiment had

an even distribution of ethnic types. While Claudette Colbert, Greer Garson

and Irene Dunne were showing us “what we were fighting for,” Rodgers and

Hammerstein, consciously or not, were creating a myth—just at the

time it was needed.

The plot? Will the nice

Curly or the evil Judd take Laurie to the picnic? (No joke, that’s all

it boils down to.) Since that is not exactly what is needed to fill up

over two hours on stage, the required second plot involves Ado Annie and

Will and the sort of life they will lead. Not very promising.

However, using the plot

of “Green Grow the Lilacs” (a flop), the team gave the audience (again,

above and beyond the score and lyrics), believable people living in a

territory that is not yet a state, going through a small crisis that will

or will not lead to marriage and babies, and somehow tying together the

political background, the social problems (can the farmer and the cowboy

ever be friends?) and the personal relationships—all into a unified

whole that plays more like a myth than a typical musical.

As I said in at least

two past essays, the show opens up with a hymn to the crops and to a beautiful

morning. It ends with a salute to the new state and returns to “Oh, what

a beautiful morning.” (So many people still believe the show ends with

the title song!) This is just what the 1943 audiences needed: reassurance

that there will indeed be many more beautiful mornings, “when the lights

go on again all over the world,” as singer Vera Lynn was at the same time

promising the British soldiers.

“Carousel” opened (symbolically)

in April 1945, a month closely connected with the blossoming of springtime.

If the audience was surprised to find “Oklahoma!” beginning with an off-stage

solo instead of the usual chorus, how much more was the “Carousel” audience

surprised to see the first act end with the death of the leading male.

Yes, the war was just

about over and the monumental task of getting Europe back on its feet

was yet to begin. What was to be LEARNED from the slaughter that was the

result of not only a single madman but of all the “normal” people who

believed him and allowed him to “move ahead” with his plans to dominate

a planet? Again, the show tries to answer the questions of the times in

terms of individuals.

Billy is allowed to return

to make up for what he did to the daughter he died too early to know.

Although a ghost, he is still human and fails. The show ends, not with

a beautiful morning, but with advice about how to walk through a storm.

Never walking alone and having hope in your heart is the answer Hammerstein

gives us.

Of course, that is semantic

nonsense. But in 1945 it was exactly what audiences wanted to hear, because

it SOUNDED good and therefore it was good. (Years later, “Climb every

mountain” tried to deliver the same message but sounded simply pretentious.

You see, once having succeeded with that sort of ending, Rodgers and Hammerstein

were stuck with it.)

A year and a month later,

“Annie Get Your Gun” opened—again, just at the right time. The men

were back on the job and women were back on the range—the kitchen

range, that is. Factory owners could not help but notice how much better

on the whole the women worked on the assembly lines than did the men.

But in 1946, the girl that one married had to be as soft and as pink as

a nursery, not muscular and grease-stained like Rosie the Riveter.

However, Annie still

outshoots the male competitors, showing once again that a woman can do

anything you (males) can do. Just the right thought at the right time,

although many of the males in the audience took it all as a joke. After

all, how many Annies are there in real life? (More than men care to admit,

as in the current bid for the presidency.)

The question of the times

influencing the musical and the musical influencing the times certainly

deserves closer and deeper and more extensive study than just this superficial

look. Perhaps future essays in this journal will be devoted to just that

subject. Yes, “Show Boat” is certainly a candidate. Do my readers have

any other suggestions?