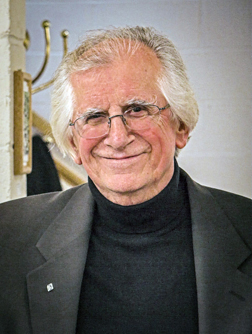

Raymond J. Steiner ~ Art Critic, Editor, Author and Artist

Raymond J. Steiner |

Raymond J. Steiner (1933 — 2019) was an art critic/ reviewer for ART TIMES, a literary journal he helped found in 1984 and for which he served as Editor. ART TIMES was the “go-to source” for essays and articles about the arts and for painters, sculptors, film makers, actors, musicians, writers and people looking for calendar listings, opportunity listings, arts schools, theatre auditions, juried art shows, performance locations, and writing competitions. In 2016 ART TIMES ceased publishing in print and continued online as arttimesjournal with profiles, essays, short fiction, poetry accessible. His many published works includes The Vessel of Splendor: A Return to the One; The Girl Who Couldn’t See (a book for young adults); Quarry Rubble (a book of poetry); 23 Woodstock Artists; Heinrich J. Jarczyk: Toward a Vision of Wholeness; Heinrich J. Jarczyk: Etchings 1968-1998; The Art Students League of New York: A History; and a novel, The Mountain. His works have been translated into German, French, Polish, Chinese and Italian. He was aMember Emeritus of the Salmagundi Club, a member of the Artist Fellowship, Inc., the International Association of Art Critics had been a member of the National Arts Club, American Society of Aesthetics, and the Hudson Valley Art Association. Landscape painting was an avocation of his for some years and his method has primarily been to paint on site, alla prima, and, in an effort to capture the spontaneous impression, to confine himself almost exclusively to the use of the palette knife. He had several one-person shows and was included in many group shows both in the Hudson Valley and New York City.

Landscape Painting

by

Raymond J. Steiner

Published in ART TIMES P&P November 2010

I PAINT LANDSCAPES —not as a professional, but as an avocation, as a way to relieve the stress of occasional writing blocks, since, as most know, writing is my profession. And yet — though only a kind of relief, an outlet for frustration — there is a deeper intent in my painting of landscapes. Obviously, if it were only a diversion, then why not still lifes? Or portraits? Or street scenes? The answer is that the painting of landscapes — though I’ve only been making them with any regularity since the late 1990’s — holds a greater claim on me, reflecting an ongoing love-affair with nature that has gripped me since my move from Brooklyn to the Catskill Mountain/Hudson River Valley when still a boy of 12 (in the summer of 1945, in fact). I’ve written elsewhere of that 40-acre, wooded plot in West Hurley, New York and how it affected my evolution from boy- to manhood, of how I’d learn to love, respect and fear the mysteries it held that persist to this day. My landscape painting — my personal replications of nature — attest — even, one might say, pay homage to — that life-long love affair.

I’d recently been interviewed by a high-school student who, armed with 20 questions prepared by her teacher, questioned me on my painting — and especially of my painting of landscapes. Although I’d been interviewed many times about my writing, this was the first time that I was asked about my painting — and the process was interesting in that it made me seriously “see” myself as a painter — something I’d rarely done in the past. And, though I explained that I was not a painter — a professional painter — being surrounded by my landscapes in my study sort of made my protestations moot (at least to the young lady interviewing me). She persisted with her 20 questions — and I tried my best to answer them — and whatever the process did for her, it certainly opened my eyes to acknowledging some truths about both myself and about my “hobby”. I knew that I painted from nature because I loved nature — but had never really delved into it as I did that day as she pointed to this painting or that, and “why’d” and “how’d” and “when’d” me on those that attracted her eye. Generally, (I told her) I paint when moved, usually outside and alla prima, and, once done, set aside whatever I manage to produce until the next time I’m “inspired”.In trying to explain these steps to another person, I found that, in fact, I was often clarifying (or obfuscating) as much for me as I was for my interviewer. What “moved” me? Why that scene? Was it in the morning or afternoon? And, so on. I tried my best to explain that, since my primary occupation was writing, that I needed both opportunity as well as “inspiration” and, that mostly, it was the way light played with form, showing me both color and shadows — etcetera, etcetera, etcetera. Gradually, however, glibly answering her questions in the same manner that so many artists I’ve profiled over the past 30 or so years did for me, it dawned on me (mostly after she’d gone and I could mull it all over) that (I am sure, like those artists I’d interviewed) none of these answers really answered anything.Still, the question remains: What is it about nature that has captivated me for all these years? And why has the painting of landscapes become such an all-engrossing activity since I resumed painting after a forty-year hiatus?What draws me to nature is not merely its beauty — it is its mystery, its underlying enigma. There is not only form and color — there is geometry and equations, forces and balances, tension and accommodation, conflict and resolution, constraining laws that say, “You can grow that high, that densely; reflect that color and absorb this one; spread that far and no farther; shine forth here and shrink in darkness there; flourish here and struggle there; shimmer now and stand stock still then.” I know that if I can understand Nature’s laws, then I can understand me — my laws, limitations, potentials. If I am made in His image, then it is that image and that image alone (are we not all unique souls? Does the oak strive to be a maple? The rose, a lily?) that I must uncover, discover, live up to. I can no more follow your path than the sycamore can aspire to become a hemlock since I — like all natural beings — have been allotted my own. We do not all go to a store and buy the same size hat. So, why ought I follow someone else’s path? Accept their answers? Ape their images?I am told, that it is written in the Koran that if one wants to speak to God, then one must go to the mosque; but, if one wants to hear God’s answer, then one must go to the desert. Having no desert nearby, I have substituted my woods — and, I have indeed received some answers — at least to my questions about my path.Thus, in the process of my interview and discussing individual paintings with that student, I could glance around my study and evaluate some of the answers I have received — not to share with that student (since we can not given that it is between the Creator and the created), but to my own inner understanding and enlightenment. Some of my landscapes I had actually seen for the first time as answers — at the time of painting, I was simply too involved in the process to “stop and smell the flowers” — I had missed the fact that each of my paintings revealed just a bit more of the mystery, that each held a kind of ‘magic’ for me if not for others, if only in that one small portion of the canvas, e.g. a tiny spot of light glancing off a stone wall, a leaf, a blossom or that murky shadow alongside a tree-trunk. In many cases, the rest of the painting existed only for that one infinitesimal touch of paint, acting as a ‘foil’ for the answer — if only I took the time to see it as I was doing during the interview. In fact, it suddenly became clear that I was not painting “trees”, or “fields” or “mountains” or “woodland streams” — in short, that I was not painting mere landscapes. I never had any doubt of the mystery — of the presence of the hidden “answers” — only that I would be able to discover them! But then why should God try to trick me?In his Art and Artist, Otto Rank wrote that early artists were the first priests, the first to penetrate “God’s” answers. It was the cave-wall scribblers that were pointing the way to his fellows on how to discover “purpose”. History, however, tells us that early shamans, diviners, seers, priests and prophets had discovered this fact about nature but, instead of sharing it with their followers, chose to keep it hidden, to hoard it as ‘privileged’ knowledge that only they could interpret. They built elaborate rituals and systems to divert attention, made laws and taboos, dangled ‘salvation’ and threatened ‘damnation’ to any who would question their authority or break their taboos.Today’s true landscape painters — the ones not painting only what their eyes can see on a certain day and in a certain place — carry on that ancient tradition of listening to God’s answers. And, if you listen and look, you might start carving out your own path…

These paintings and more can be seen by contacting Cornelia Seckel

Cloud study |

||

Squall Line |

Evening |

|

Hammer of Tor |

||

Gathering Storm |

End of Winter |

|

Sawkill in Winter |

Brewing Cloudburst |