Art Essay: Out of the Shadows: Marie Danforth Page

By Rena Tobey ©2015

ART TIMES Spring 2015

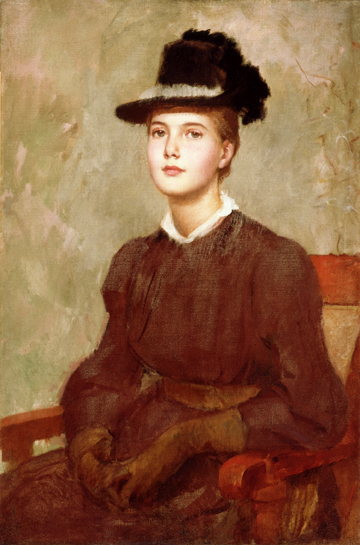

Frank Duveneck (American, 1848–1919) Frank Duveneck (American, 1848–1919) Marie Danforth Page , ca. 1889 Oil on canvas 38" x 25 ¼". Cincinnati Art Museum; Gift of the Artist, 1915.100 |

By the late 1800s, a social divide among American women prefaced radical changes coming in the new century. Traditional women still celebrated the protective sanctuary of the private sphere, a moral and domestic haven for the family. The ‘Cult of True Womanhood’ valued piety, purity, and submission. Increasingly though, even these women embraced new roles as consumers that propelled them out of the home into the public sphere of money, commerce, and politics. Women artists were also caught in a bind between the spheres. Even as professionals, bringing in respectable incomes from their work, they were pinned to conventional, private sphere subject matter.

Marie Danforth Page (1869-1940) built a reputation and a successful career making sensitive, particularized portraits of women and notably of children, themes that could be both a trap and an opportunity. Domestic subjects fit a popular demand and could be painted in private settings and from studios at home. In fact, Danforth Page’s studio was entrenched in the woman’s sphere, on the third floor of her Boston home. Critics were comfortable praising her portraits as both natural and appropriate. For an artist focused on building a career, this careful production was neither surprising, nor unique to Danforth Page. Like other women artists of her generation, what made her work outstanding was not its themes, but rather how she portrayed her sitters—the source for her creative expression.

Danforth Page did not seem to rail against these strictures. Indeed, she excelled in conservative Boston, where the Gilded Age, stretching from the 1870s until the start of World War I, epitomized the backlash that hardened old-fashioned gender roles. In art, displays of manly virility, discipline, and athleticism were celebrated, making stars out of male artists. Women were to be treasured as decoration, as cherished possessions. Even women’s role as consumer centered on creating and nurturing a beautiful Victorian home, in essence, constructing their very own gilded birdcage, one source of the era’s name.

Cannily, Danforth Page successfully straddled societal expectations with the growing demand for parlor-sized, intimate portraits. She crafted her successful painting business, first by copying famous works of earlier artists such as Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828), then transitioning to commissioning 7 to 8 portraits from prominent families a year. By the 1920s, she charged a respectable $1000 for a full-length portrait. After they married in 1896, Dr. Calvin Page, a research bacteriologist, supported her career as a portrait artist, and her earnings provided a substantial portion of the family income, essential to maintaining the Page’s Back Bay home.

Perhaps the respect and joys of their companionate marriage prompted Danforth Page in 1909 to create her most intriguing work, the portrait of her husband Calvin Gates Page. The style varies dramatically from the bright, Impressionist palette of her other work. Her husband is dressed plainly, bathed in warm browns, holding a document that is perhaps work related. His face is harshly lit, thrusting out of his dark suit jacket and the dim background. His expression is serious, his lips slightly parted as if gently surprised by the artist, yet his eyes are warm, curious, and open. Perhaps Danforth Page has caught him just before a smile. She renders her sitter with believable naturalism and subtle, varying textures: Dr. Page’s soft and wispy moustache, the hair-thin outline of his rimless glasses, the starched white collar, his slightly rumpled tie.

Marie Danforth Page (American, 1869-1940) Calvin Gates Page, 1909 Private Collection Marie Danforth Page (American, 1869-1940) Calvin Gates Page, 1909 Private Collection |

The painting is so much more than the bravura of this depiction. It is complex both stylistically and psychologically. Danforth Page seats her husband in front of a mirror, a device she employed in several portraits. The mirror, while demonstrating mastery of technique, also triggers uncertainty and discomfort in the viewer. It shows the reflection of the artist herself in deep shadow, her face unreadable, standing with palette and paintbrush. The brushy paint application, seen on the contours and folds of her dress, and the play of light on her hair emphasize rather than reduce the figure. She seems to suggest that no matter her talent as an artist, she is present, yet diminished, as if living in the shadow of her husband, a woman of the Gilded Age. Also in the mirror, but brightly lit and clearly readable, is a portrait of a child hung on the wall. Portraits typically include elements that suggest something about the character of the sitter. Dr. Page appears to be looking at and considering his family, suggesting their importance to his identity.

But all is not as it seems. The child in the portrait within the portrait is not the Page’s son. This portrait is of four-year-old Malcolm Stone, whose family lived across the street and were great friends of the Page’s. Instead of showing off her own child, Danforth Page is instead indicating her typical subject, as if the painting were a calling card for prospective sitters. The device of using a mirror to reflect the artist at work was notably used by Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) in 1656 with Las Meninas, a work Danforth Page may have copied along with his other works while in Spain. Velázquez, and by extension Danforth Page, are elevating the role of the artist, by making the act of painting visible, and indeed central, in each painting.

The mirror device gives Danforth Page the opportunity to demonstrate mastery of multiple perspectives. Artists have used a mirror to symbolize the act of looking, the Gaze that the viewer takes for granted, such as the right to gaze at portrait sitters and nude figures, generally women. Dr. Page looks directly back at the viewer, as if challenging the authority of the viewer’s Gaze. The mirror shows the artist gazing at her subject. The mirror also engages the viewer in a modern way of understanding the painting. If the viewer stands in front of Dr. Page, and so does the artist, then the viewer is placed in the position of the artist. If he is considering her, as his wife and presumably mother of his child, but also looking directly at the viewer, then again, the viewer becomes one with the artist. The viewer, then, is placed in the vantage point of the artist, as if to ask the question, what would it be like to be married to this man?

Further discomfiting is Danforth Page’s figure. If she, as artist, is a central figure in this portrait, then why does she position herself standing in shadow? The light source highlights Dr. Page’s face and the child’s portrait, while only brightening the artist’s painting smock and the side of her neck. Her face is illegible, no matter how hard the viewer tries to make out her expression. Rather than mysterious, this shadowing is frustrating. It also has the effect of making her seem wistful. But about what? By 1909, Danforth Page was entering her most productive period, self-confident and assured in technique. She generated steady income, maintaining records of her commissions, sales, and prizes in a receipt book. Sensible in her business dealings, she painted routinely every day, insisting that her sitters come to her studio, rather than take the time to travel to them.

Why then would this capable woman show herself in shadow? Perhaps she did feel trapped by the limitations of subject matter and gendered artist roles. Perhaps she aspired to Velázquez-level recognition. Rather than caged, perhaps Danforth Page was so assured that she chose to acknowledge herself by highlighting her work instead of herself, boosting her husband in this odd celebration of family. Perhaps she is showing some separation from her husband, some distance, that indicates what their relationship may have really been like: he luminous, while she fades into a pool of darkness.

The interpretations could go on, but likely will remain unanswered. Danforth Page herself avoided explaining her work. What is known is that Danforth Page painted portraits of children with maternal tenderness, considering the portrayals “the most amusing and beautiful subject.” The couple adopted two young girls, Margaret and Susan, in 1919, when she was 50 years old. Also known is that Danforth Page was criticized for painting with a bold technique that was considered too masculine. Her brush strokes were too virile. If she strayed from feminine charm or sympathy in subject matter, then her work ceased to be feminine, creating a threat to male control of the art world. If she worked quietly in the background, as Danforth Page depicts herself in her husband’s portrait, then she fails to be acknowledged for her worth, as Velázquez was for his, risking loss of patronage as well as self-esteem.

Danforth Page was not alone in suffering from this double standard. Whereas male artists could enter the private sphere to paint sumptuous interiors, women painters could push the boundaries of the public sector only at some risk. Women could not appropriately paint scenes of theater and ballet dancers, taverns, or teeming streets. The murkiness of this negotiation perhaps is nowhere more evident that the intriguing and baffling portrait of Calvin Gates Page.

This essay is the forth from the "Finding Her Way" series, exploring the challenges American women artists faced from about 1850 to 1950.

Previous essays:

Elizabeth Okie Paxton Summer 2014

Lilly Martin Spencer Fall 2014

Alice Barber Stephens

Winter 2014