Theater: What Is Good Acting?

By Wendy Caster

arttimesjournal February 8, 2017

Sarah Bernhardt in 1865 (Photo: Félix Nadar) |

Good acting is a matter of opinion. A performance that you perceive as brilliantly emotional, I might perceive as overacting. A performance that strikes me as subtle might strike you as dull. Many factors affect our opinions, including performers’ talents, looks, and charisma—and whether they resemble someone we used to date.

On the other hand, certain characteristics are generally agreed to define good acting: fully inhabiting the character, having a good voice, etc. But aren’t these also opinions? And don’t opinions change?

Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), Laurette Taylor (1883–1946), Colleen Dewhurst (1924–1991), and Cate Blanchett (1969– ) have all been lauded as great actresses, but would they have been as successful in different centuries? Would the natural Laurette Taylor bore audiences in 1890? Would the rawly honest Blanchett seem vulgar in 1940?

Since we can’t go back and see the four actresses’ live performances, I thought it would be interesting to track down how people described their work at the time.

Sarah Bernhardt and Laurette Taylor. When I was young, I often asked older theater-goers, “What’s the best performance you’ve ever seen?” And the answer was always the same: Laurette Taylor in The Glass Menagerie.

Well, not quite always. In the early-ish ‘70s, I studied Theater and English Literature at Queens College. A bow-tied old man named Henry came to many of the shows we put on. When I asked him what was the best performance he had ever seen, he said “Sarah Bernhardt in Hamlet.” Henry, it turned out, was in his 90s. He had seen Bernhardt when she still had both of her legs!

Laurette Taylor in The Glass Menagerie |

Here’s the interesting thing: Laurette Taylor was considered to be the first totally natural theater actress. She was, in many ways, the antidote to Sarah Bernhardt, whose highly theatrical, ornate style had fallen out of style. Yet Henry preferred Bernhardt. Is it because he grew up when hers was the accepted style of acting, and she was the best? I wish I had asked.

Sarah Bernhardt’s reviews were full of excitement. A man named Pierre Wolf wrote, “On the stage she loved and she cried, not only with all her soul, but with all her body … Moreover, she was a musician through her voice -- that voice of gold which was a song, a lullaby, a melody … which could be modulated to an infinite sweetness, obeying secret laws which seemed always impromptu, always changing, always new. Critic Lytton Strachey wrote, "She could contrive thrill after thrill, she could seize and tear the nerves of her audience, she could touch, she could terrify, to the top of her astonishing bent." On the other hand, George Bernard Shaw said "she does not enter into the leading character: she substitutes herself for it.”

Although the term was not yet in use, Bernhardt was a superstar in a way that puts the Beatles and Beyonce to shame. As you can see on YouTube, when she died, all of Paris turned out for her funeral procession. It’s really worth watching.

The raves that Laurette Taylor received in A Glass Menagerie all focused on her ability to disappear into the character. Actor Martin Landau said it was “Absolutely like this woman had found her way into the theater, through the stage door, and was sort of wandering around the kitchen.” Actor Charles Durning said, “I thought they pulled her off the street. She was … so natural.” But she was more than just Amanda Wingfield, at least according to Tennessee Williams: “There was a radiance about her art which I can compare only to the greatest lines of poetry, and which gave me the same shock of revelation, as if the air about us had been momentarily broken through by light from some clear space around us.”

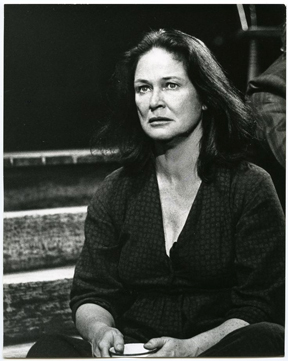

Colleen Dewhurst in A Moon for the Misbegotten |

Colleen Dewhurst. The best performance I’ve ever seen? Colleen Dewhurst in A Moon for the Misbegotten. I saw her three times: last row mezzanine, 14th row orchestra, first row orchestra. Her performance was exquisite from any location. She was completely real yet larger than life, a combination that strikes me as ideal for theater. She had a subtlety that was only visible from the first few rows, but she also used broad strokes that could be seen and felt from the last row. Hers was a magical balance, and her presence was extraordinary.

Clive Barnes of the New York Times wrote, “She spoke O'Neill as if it were being spoken for the first time—and not the first time in a theater (you always hope for that) but for the first time in a certain New England farm, on a certain September night in 1923.” In the same paper, Walter Kerr wrote, “It is difficult to take your eyes off Miss Dewhurst, whether she is smiling or in fury… Most smiles, when they are about to crack in dismay, crack downward. Hers shatters upward, sustaining the shape of happiness while a telltale quaver makes a lie of the crescent corners of her mouth. Her face seems actually to brighten under the hint of pain, a sense of unruly merriment tries hard to assert itself, a vixenish gaiety becomes permanent companion of disaster.”

Cate Blanchett in A Streetcar Named Desire. (Photo: Richard Termine) |

Cate Blanchett. Cate Blanchett in Streetcar inspired New York Times critic Ben Brantley to wax lyrical: “The lady who lives for illusion has never felt more real. Playing that immortal bruised Southern lily Blanche DuBois, … Cate Blanchett soars spectacularly on the gossamer wings of fantasies that allow her character to live with herself. But you never doubt for a second that this brave, silly, contradictory and endlessly compelling woman is thoroughly and inescapably of this world.”

In the New Yorker, John Lahr wrote, “Blanchett, with her alert mind, her informed heart, and her lithe, patrician silhouette, gets it right from the first beat... Blanchett doesn’t make the usual mistake of foreshadowing Blanche’s end at the play’s beginning; she allows Blanche a slow, fascinating decline. And she is compelling both as a brazen flirt and as an amusing bitch.”

In Vogue, Adam Green wrote, “Blanchett charts every nuance of her character’s downward spiral and captures each of her seemingly endless contradictions with dazzling facility. But her real achievement lies in making us feel that we are watching a real person flailing to keep her head above the rising tide.”

I agree, however, with Jayne Blanchard of the Washington Times, who wrote, “As directed (one wonders, overdirected) by Liv Ullmann, Miss Blanchett acts up a storm, but fails to inhabit the character or make you see beyond histrionic technique. As a result, you never sympathize with Blanche or fall under her faded spell.”

To Each Her Own. If we could take a time machine to Bernhardt’s Hamlet, what would we think? A lot of us might find Bernhardt painfully hammy. Yet Cate Blanchett, who played a broad-stroke Blanche, was greeted by cheers and standing ovations in Streetcar. It was the performance’s very size, I think, that people loved.

Have we come full circle from Bernhardt to Blanchett? Not exactly. Many performers still win awards for completely realistic acting. And after working on this piece, I’ve come to the conclusion that we are lucky to live in a golden age that has room for many acting styles.

Sources

Sarah Bernhardt reviews are from the LA Times.

The quoted material about Laurette Taylor is from The Greatest “Menagerie” by Robert Gottlieb in the New Yorker.

( Wendy Caster is an award-winning writer living in New York City. Her reviews appear regularly on the blog Show Showdown. Her short plays You Look Just Like Him and The Morning After were performed as part of Estrogenius festivals. Her published works include short stories, essays, and one book. )