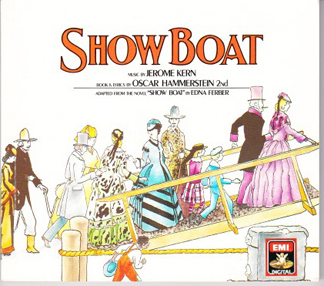

Music: The Integrated Musical – Part 2

By Frank Behrens

ART TIMES January/ February 2013

|

A show boat. On it is the lovely star of the shows, Magnolia. A no-account gambler named Gaylord Ravenal drifts her way and chemistry does its thing. As it happens, there is an opening for an actor and Ravenal applies for the job. But Magnolia must ask for qualifications. Could he possibly make believe that he loves her as a character in the play? After about 20 lines of verse, the refrain begins with “We could make believe” and an American classic is born.

Now this is the best example I can think of in “Show Boat” of a song that flows directly from the dramatic situation on stage, even down to the detail that he is applying for a job as actor and answering her question at the same time. No other characters in the show could have sung this duet and this duet could not have been sung at any other time in the show.

I must point out that as closely as “Make believe” is plot-related, it can also be sung as a straight love duet out of the context of the show—and indeed has been.

Of course, not every song in a musical can be tied in so closely with both plot and character as much as “Make believe.” “Life upon the wicked stage” was motivated by the curiosity of some female characters, but the sequence did not have to be included at that point in the show.

On the other hand, “Ol’ man river” does have to come close to the opening of Act I. While it serves no dramatic purpose, it sets the theme and provides the leitmotif for the show as a whole. The fact that the overture begins with a powerful statement of that melody adds great emphasis when it is sung so soon afterward.

So let us pause for a moment. It is easy to define an integrated song. Can we conclude, therefore, that a musical with a preponderance of integrated songs makes an integrated musical?

Back in the second decade of the last century, three men thought along those lines. When someone discovered a tiny little 299-seater in Manhattan called the Princess Theatre, she saw its possibilities as a place to produce shows that could not be elaborate but must of necessity be intimate (and therefore cheaper to produce). This attracted a team consisting of Jerome Kern (music), P.G. Wodehouse (lyrics) and Guy Bolton (book), who set about creating musicals that were plot driven and in which even the members of the chorus would be given individual names and—wonder of wonders—lines to speak.

Many women deserted the winding steps of the Ziegfeld Follies, longing to be actresses rather than clothes dummies. Of course, the plots were not masterpieces of theatre. They were pretty much Americanized versions of characters found in satirical British novels of the time—idle playboys and innocent but adventurous girls from Long Island.

(Considering that Wodehouse moved out to Long Island to write (among other things) his Jeeves novels, it is no wonder that the characters in the Princess musicals are what they are.)

No, although the three tried to create musicals in which a song came in at just the right moment, those songs were still standard ballads and ensembles, albeit zipped up with the clever Wodehouse lyrics.

Take for example the 1917 “Oh, Boy!” There is a plot and a complicated one, but I found myself hard pressed to find a song that advances the plot. “’Till the clouds roll by” is an expression of attraction between two characters who have just met. “A little bit of ribbon” must be sung at the moment when the female chorus sees some wedding finery, but the song itself adds nothing dramatically. And “Nesting time in Flatbush” is not more than an anticipation of happy wedded life for a loving couple.

However, granted all this, the audience feels that each song is just where it belongs; and I believe that is because there is a plot in which the action moves from point to point and the songs simply seem to go along with it.

The question of integration no longer exists in current musicals, because (I believe) that they are would-be operas or at least drama-with-music. But that is a subject for quite another essay.

Frank Behrens: fbehrens@ne.rr.com