Share |

Music: The Integrated Musical—Part 1

By Frank Behrens

ART TIMES November/ December 2012

|

What exactly is an integrated musical? Among the many definitions is “a show in which the musical aspects blend in strongly with the dramatic aspects.” Examples are better than definitions. There, it would be well to look at some of the non-integrated moments in a musical better to appreciate the integrated ones.

Listen to any of the Gershwin or Rodgers and Hart musicals of the 1920s and 1930s. Many of the songs are perfectly transferable not only from one act to another but from one show to another. “The man I love” was written for “Lady Be Good” but dropped, then transferred to “Strike Up the Band” but dropped, and then it wound up in “Rosalie” and dropped a third time, and finally it was published as an independent song in the Tin Pan Alley tradition. And the music of one Rodgers and Hart piece had three sets of lyrics before settling as an independent piece with the title “Blue moon.”

You see, it was important that most lyrics did not refer to any character or plot element exactly so it could be moved around. “Love song here” or “comic duet here” was all that was needed in the infant script of a musical.

(When Gilbert & Sullivan were deep into rehearsals for “The Mikado,” the soprano asked if her only solo, “The sun whose rays,” could be put into Act II. It seems Gilbert put it after two other numbers that included her character and she was quite out of breath after the second one. So now that lovely song appears early in Act II and very few audiences are any the wiser, because it is so detachable.)

Even in the more mature works of the next three decades, not every song was essential to the plot. “On the street where you live” is merely a statement of the singer’s emotions at the moment. Nothing changes; things are exactly the same after the song as they were before it. If the song had been cut before opening night, no one would have noticed any gap in the action. The same could almost be said about “I could have danced all night.” And take note that both were recorded as “singles” by several vocalists.

But surely, one can respond, this is indeed a musical, and songs that express emotion should not be considered as interpolations and of no dramatic value. Take from Hamlet his “To be or not to be” and nothing would have been missed on opening afternoon at the Globe. The Prince still has the same doubts he had before the speech as he does after it. But what a loss it would have been!

Yet in a way Liza’s joyful song comes—as “Street where you live” does not--at just the right point in the act. For the first time since entering the Higgins household, she is truly happy. So while the song does not advance the plot in the least, (1) it could not have been sung at any other time in the show, (2) it tells us more about the character than we knew before, and (3) it provides a wonderful contrast to her disappointment after the ball, when she is most miserable.

So what is an integrated song? “The rain in Spain” is among the most integrated musical songs of them all. Liza has finally pronounced the sentence correctly, according to Higgins and Pickering, and the three characters keep repeating it without music and finally sing it to a Spanish beat with variations. Things are not the same in that household because of the song. In fact, “I could have danced all night” refers to the Flamenco dance steps they improvised in the previous number. The first moved the plot, the second gave Liza and the audience a chance to think about it.

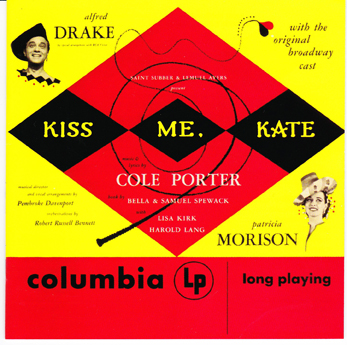

In “Kiss Me Kate,” we have (1) songs sung in the dressing rooms in the theatre and in the adjacent alley and (2) those sung as part of the show-within-the show. “Wunderbar” is sung by the ex-spouses, Fred and Lilli, recalling a moment of happiness from their nuptial past. It lets us and the characters realize that they could be happy together again; but the feeling is fleeting. “Why can’t you behave?” gives us an insight into the problems of the secondary couple, while “True to you in my fashion” is a clone, intentional or not, of Ado Annie’s “I cain’t say no” in “Oklahoma!” It is pure character portrayal that does not advance the plot at all.

Yes, songs that reveal character are very important elements of a musical, and if they seldom if ever advance the plot, that is not important.

“So in love” again is a purely emotional number, but its reprise in Act II brings the quarreling couple back together. (In fact, directors have to bring Lilli back onto the stage to hear this reprise, something Porter seems to have neglected. If she doesn’t hear him sing how much he still loves her, what motivates her to return to the show?

The songs within the “Taming” sequences do not enter into this analysis and call for a different approach than the one I am using here.

So what shows come closest to being “integrated” and what is so special about them otherwise? That is the question at which I would like to start in the second part of this essay.

Frank Behrens: fbehrens@ne.rr.com