Music: Mythic Elements in Works for the Musical Stage:

The Unknown Prince

By Frank Behrens

ART TIMES Sept/ Oct 2011

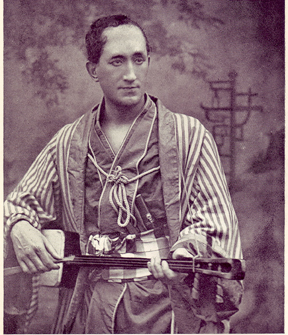

Durward Lely, the original Nanki-Poo, disguised Prince of a godlike father, in Durward Lely, the original Nanki-Poo, disguised Prince of a godlike father, in “The Mikado” |

They say there are only seven basic plots and that any work of fiction is a variation on one of those seven. Don’t ask who said that or what those seven plots are, because I couldn’t be that precise. But assuming it is true, I would like to return to a theme I handled quite a few years ago in this journal, namely Myth in Opera.

Back then, I devoted several articles to operatic treatments of myth, such as Gluck’s two Iphigenia operas (one of which is was recently shown at the Metropolitan Opera, on television, and in movie houses), Handel’s look at the last days of Heracles, and Strauss’s take on Elektra. In this essay, however, I want to turn things around and look at mythical elements in operas and other works for the musical stage that have nothing to do with retelling the original ancient tales but retain aspects of the same mythic concepts.

Perhaps an example will make things clearer. One frequent feature of many myths is a young man who is the son of a god or goddess, traveling in disguise for some reason or another, but usually to win a fair princess. Well, if we allow the Mikado of Japan to be a divine being, then his son Nanki-Poo fits the bill nicely.

Disguised as a second trombone and a singer of ballads “cut and dried,” he wants to win the lovely Yum-Yum. But to do so, he must defeat two monsters: the timid ex-tailor, now Lord High Executioner of Titipu, Ko-Ko; and the horrendously ugly (except for her left shoulder-blade and right elbow, which are miracles of loveliness) Katisha, the Mikado’s Daughter-in-Law Elect. To get his girl, Nanki-Poo must agree to be beheaded after one month’s conjugal bliss, a situation not unlike that of Sir Gawain vis-à-vis the Green Knight.

Did Gilbert have all this myth in mind when he came up with the scenario? I would not dare second guess. But the elements are certainly there.

The Prince in “Turandot” has a special problem. The monster he must slay to get the girl he wants is the girl herself, the man-hating Princess Turandot. Where Oedipus had but one riddle to solve, the Prince must solve not one but three riddles of Florentine complexity. Like Perseus who had to go to the three Grey Sisters (with one eye between them), this hero is confronted unwillingly by the advice of the three court officials Ping, Pang and Pong. And by offering to sacrifice himself by posing a riddle of his own to Turandot, he displays the heroic aspects of so many of his cousins on the musical stage.

“The Magic Flute” is told like a fairy tale to begin with, but again we have the Prince in disguise, Tamino, who is commanded by the Queen of the Night (a sympathetic character in Act I, a blatant villainess in Act II) to rescue her daughter Pamina from the evil Sarastro. Being a Masonic allegory, the plot has both Tamino and Pamina risk ordeals of water and fire (not very dangerously, since he has the magic flute to help him), and when he gains self-knowledge, he wins the bride.

Although “Lohengrin” is an opera based on a Teutonic myth, it makes use of a classical myth for its climax. Elsa is accused by a knight named Telramund of doing away with her brother, and the issue is left to a trial by combat between her accuser and whoever acts as combatant for the defense (I suppose you would call it). Out of the mist and riding on a raft pulled by a swan, Lohengrin appears and needs only a few bars of music to beat his opponent to the ground. This seems automatically to mean wedding bells (and the world’s two most famous wedding marches) for the yet unnamed knight and Elsa.

For reasons of his own—which boil down to “There is no love without trust”—he refuses to tell her his name. After a few plot turns, Lohengrin says he feels betrayed that Elsa asked for his name and feels he must announce it all. His name is Lohengrin and his father is Parsifal, Guardian of the Grail. He exits by swan.

Now since a wife is forbidden to do or say a certain thing and she is driven to disobey in this tale, it should immediately bring to mind the story of another such situation, that of Cupid and Psyche. Psyche was so beautiful that worship of Venus fell off to the point that the goddess vowed revenge. She sent her son Cupid to have Psyche fall in love with the vilest creature possible; but the young god was smitten himself.

Psyche winds up with a husband whose name she must never ask and whose body she must never see. (This makes Lohengrin seem very reasonable.) Goaded by her sisters, she does approach her husband as he sleeps and finds him to be the fairest man she ever hoped to see. At the end, the Olympians agree to let the marriage last—and Cupid (Love) and Psyche (Soul) were forever united.

We will continue to consider the Unknown Prince theme and that of the Trickster in the next issue.