Music: The Jerez Festival

By Justine Bayod Espoz

ART TIMES May 2014 online

Joaquin Grilo's Cositas mias |

There are many who automatically think of a long-legged, pink bird synonymous with 60’s kitsch, when they hear the word flamenco. It can be uncomfortable having to point out that the colorful waterfowl that they are referring to is actually a flamingo. However, for those of us who know and love flamenco, the Spanish art form comprised of live music and dance, it can be equally as uncomfortable to know that those who don’t think of flamingos may have nothing more than a clichéd notion of polka dots and frilly dresses. Much like any art, it takes time and exposure to fully understand flamenco's complexity, certainly more than just a quick visit to a tablao while on vacation in Spain. To see flamenco at its grandest and most varied, Spaniards and foreigners alike must look to some of the world’s largest yearly flamenco gatherings, where they can not only see a broad scope of productions but also a varied selection of artists and styles.

The Jerez Festival, held annually in Jerez de la Frontera, Spain (cradle of flamenco and sherry wine), is undeniably one of the world’s most important flamenco experiences, hosting 16 days of performances (between two and three shows per night) and two weeks of morning and evening workshops led by some of flamenco’s most renowned dancers and musicians. The festival draws diehard flamenco enthusiasts from across the globe who want to study with their icons and to catch the flamenco scene’s most recent productions.

The last five years have been hard for the festival and flamenco in general. The international economic crisis, which has been particularly devastating in Spain, has led to cuts to cultural programs, and national, regional and local grants for the arts have been slashed as municipalities, autonomous communities and the national governments teeter on the edge of bankruptcy. Despite its longevity – 18 editions – and impeccable reputation, the Jerez Festival has suffered continuous budget cuts, and worldwide economic hardship has seen a yearly decline in the number of patrons attending from abroad.

Economic pressures may well have been a primary cause for uninspired programming over the last few years of the festival, which opted for big names rather than overall production quality. The hope was that repeatedly programming well-known headlining names such as Maria Pages and Farruquito would sell more tickets. But few international and even national flamenco enthusiasts will pay for a trip to Jerez just to see shows that will tour extensively over the subsequent years. Most patrons attend the festival looking for those precious gems that they may never have the chance to see in their hometowns.

Domingo Ortega accompanied by Fernando de la Morena on vocals and Sandra Guerrera and Mari Paz Lucena on palmas in El baile canta |

The Jerez Festival took a much needed change in tack in 2014, finally focusing on giving young and promising artists a larger presence and programming artists that had bewilderingly been left out of the fold edition after edition. One such artist was Jerez’s native son Domingo Ortega, whose one and only participation in the festival had taken place eight years earlier. The flamenco dancer insists that he’d since submitted several proposals for shows, as had his flamenco dancer sister Inmaculada Ortega, but that both had been ignored. By 2013, Ortega had thrown in the towel, expecting never to participate in this important festival again and unsure of why, but that spring he received a phone call from festival director Isamay Benavente, requesting that he create a show for the festival’s main stage. Her only requirement was that it be a “pure” flamenco performance, a request that suggests that the festival may have been reacting to the negative response of many journalists and audience members who felt that previous years’ programming was too heavy on a style of flamenco that fused – many times unsuccessfully – flamenco and contemporary dance.

Ortega was happy to oblige, and in ten months he created a large-scale production that was one of the highlights of the 2014 program. After being left outside of the festival loop for so long, one would imagine Ortega was hungry to prove his worth by making himself the center of attention, but Ortega took a completely different approach in El baile canta (The Dance Sings). His dance professor and the man that made him principal dancer of the Albarizuela Ballet in his youth, Fernando Belmonte, was invited to participate as artistic director, legendary Jerez singer Fernando de la Morena was a guest artist, and Ortega shared the stage with two excellent female dancers Sandra Guerrera and Mari Paz Lucena. Against a backdrop of beautiful projections of the morning, evening and night skies, a magical string of solos, duets and trios portrayed a broad variety of flamenco styles and tones.

The show, however, was not flawless. In a repertoire of almost entirely classical flamenco music, the inclusion of a rock song sung by Ortega and flamenco singer Sonia Bérbel and accompanied on electric guitar by Juan Delola was jarring and briefly obstructed the otherwise natural flow of the performance. And there was a long stretch in the middle of the performance during which Ortega is completely absent. Although watching the women dancers was beautiful, Ortega’s presence is missed. It is after all his show, and his large and grounded presence would have made a nice contrast to his female counterparts if interspersed throughout rather than relegated to opening and closing the show.

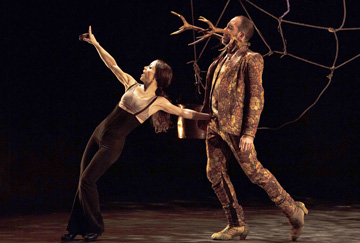

Olga Pericet and Juan Carlos Lérida clash in Pisadas |

Two nights after Ortega’s premiere came Olga Pericet’s debut performance of Pisadas (Footsteps). This diminutive dancer has become a regular on the festival’s main stage. It’s not surprising that she’s a programming favorite, as she is tremendously versatile and versed in classical Spanish dance as well as flamenco. Pericet is an accomplished choreographer, unafraid to venture into uncharted flamenco territories. Pisadas is her most oddly fantastic contribution yet.

The work alternates boldly traditional flamenco scenes and performances with unapologetically contemporary scenes that are entertainingly, head-scratchingly strange, such as her duet with guest artist Juan Carlos Lérida. Uneven rope netting serves as a backdrop as Lérida emerges from the wings, large antlers strapped to his neck. At one moment he prances dear-like across the stage and at another wows with flawless flamenco footwork. He is soon joined by a wild Pericet clad in a beige bra and the high-waisted flamenco pants usually worn by men. The two battle. As arms lock with horns, the mood is at time serious and at times humorous, such as when the stag’s testicles become a target and means of triumph. The size difference between the two dancers alone is reason to chuckle. Battle scenes, especially those of matador and bull, are common in the flamenco cannon, but putting a new twist on this type of dance scene updates and refreshes it.

Pisadas is in fact the depiction of a struggle, one between tradition and orthodoxy and modernity and experimentation. Despite being at odds, Pericet doesn’t seem to favor one over the other, but rather embraces them both, giving each its space and time. Many audience members emerged from the performance perplexed, seemingly unable or unwilling to accept that two such different styles could co-exist in a single work. In these cases it is often best not to overanalyze, but enjoy ourselves by freely and trustingly following the artist into the weird. Once we’ve allowed ourselves to be absorbed, the overall message may not be so difficult to decipher or accept.

Joaquin Grilo dancing for Remedios Amaya in Cositas mias |

Although Joaquin Grilo is Jerez Festival royalty and one of the most famous flamenco dancers to emerge from the City of Jerez, he has also run into opposition when it comes to his entirely original style of flamenco dance. Grilo is a dancer who has reinvented himself a few times throughout his career. His most recent incarnation has brought him international acclaim and fame, but also scorn from some flamenco purists. Grilo is an impeccable flamenco dancer with classical dance influences that bring a certain grace to many of his movements. He doesn’t dabble in fusion; however, Grilo counters the typical elegance and formality of orthodox flamenco with a looser more playful influence that at times resembles an American tap dance aesthetic.

Grilo closed the XVIII Flamenco Festival with what is without a doubt one of the best productions of his career, Cositas mias (My little things). As the title suggests, this performance is intensely personal, a production made above all to move Grilo’s own spirit by remembering all of those people who have influenced his artistic life. It’s been a while now that Grilo has wanted to build a show around the musicians who inspire him, and while he says that budgetary constraints prohibited him from inviting everyone he would have liked, he was able to showcase flamenco pianist Dorantes and legendary singer Remedios Amaya. The result is a perfectly balanced yet visceral show that allows Grilo to show just why he is one of the world’s foremost flamenco dancers, but also graciously allows his musicians their own space to marvel the audience. The moment during Dorantes’ solo when he tickled the ivories with his left hand while plucking at the grand piano’s stings with his right, as though playing the guitar, was an unforgettable instance of musical bliss.

Grilo closed his performance with an homage to flamenco guitarist Paco de Lucia, the man with whom he toured for seven years and who passed away suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 66 on February 26th. The finale of Cositas Mias sees a physically and emotionally exhausted Grilo become slowly engulfed by his musicians. As his arms rise above the dark group of bodies, a spotlight focuses on the guitar gingerly gripped in his hands, and together the group of artists sings lyrics composed in the maestro’s memory, “Strings sound / cousins cry / it smells like cinnamon / the essence has left / abundant flows / inspiration is gone / de Lucía took it with him / how many moments in my memory.”

It is moments, performances and artists like these that make the Jerez Festival memorable regardless of the occasional programming faux pas and unending budget cuts. Those interested in immersing themselves in flamenco need look no further than Jerez from late-February to early-March. It is without a doubt the best time to enjoy the music, the dance, the wine and, above all, the atmosphere.

Videos of some of the performers

Domingo Ortega: https://vimeo.com/87628934

Olga Pericet: https://vimeo.com/87831490

Joaquin Grilo: https://vimeo.com/88571839

Justine Bayod Espoz holds BAs in English and Spanish Literature and a Master's in Cultural Management. She writes about Arts and Culture for a variety of international publications and is based in Madrid, Spain and Chicago.

Share |