Vojen Cech Colini: Old World Artist Meets Digital Age Art

By PAT MUCCIGROSSO

ART

TIMES Apr,

2004

(Photos Courtesy

the Author)

|

|

Vojen Cech Colini is a surrealist, quite possibly the oldest, living surrealist. Just months away from his 80th birthday, Colini continues to paint in a style that is considered by some to be an artistic anachronism.

"I paint what I like. I never left what I liked." The artist sits at a small, round table in his home in Clark Summit, Pennsylvania digging through a box of sketches and early paintings. "I was very young when I started painting…innocent and naïve."

He pulls out a small, breathtaking image. The jeweled tone of the uniform worn by the single figure in the foreground literally glows. It is one of Colini’s first. "I didn’t know much about the 15th century," he says, holding the image in front of him. "But I loved it." Then he laughs and adds, "This is not bad."

Colini was born in 1924, only 17 years before the surrealist movement was declared dead. The day Nazi tanks rolled into the town square of Colin, Czechoslovakia, the13-year-old boy was sent to Lucerne to study. There, Colini began a life-long love affair with art.

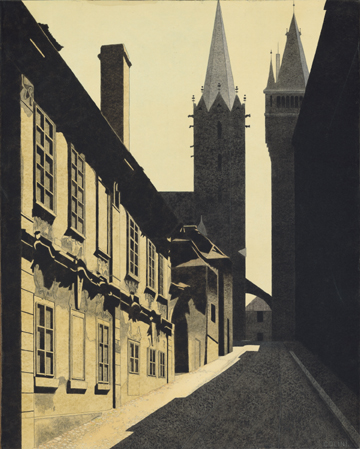

His summers were spent in the churches and museums of small towns in Italy where he fell under the spell of Renaissance painters. In his late teens, Colini traveled to Paris. Surrealism was at its peak. There, he enjoyed the company of such masters as Rene Magritte and Max Ernst but it was the images of Giorgio de Chirico, another surrealist, which captured the young painter’s eye.

Drawn to the contrast between light and shadow, the strange perspectives and bizarre environments that were de Chirico’s signature, Colini began to marry the surrealist vision of the fantastic with his other love, 15th century renaissance art. He even adopted the medium of tempera as his own.

"Tempera gives you absolute control, the plasticity of dark and light," Colini holds up a painting. "You can do things with tempera you can’t do with oils. With oils, you have not as much finesse, no control"

Painting with oils is difficult; painting with tempera is close to impossible. Unlike oil painting, where layers of paint add depth and contour to images, tempera paintings gain depth in both field and color by the deft mixing, application and layering of egg glazes. A single color on a finished painting could take as many as 6 different glazes to achieve.

It was the colors that tempera made possible that really fired Colini’s imagination. "The paintings of the masters glowed – such strong colors and so beautiful," his voice carries you with him to the museums and galleries of Italy. "They have been dead for 500 years but when you see their paintings, you can see, hold, understand what life and the artists were like."

The colors in Colini’s paintings glow as well, lit from within. The clarity and high gloss of the images almost fool the eye into thinking they are photographs. But there is no place on earth where you could photograph the images that fill Colini’s paintings.

|

|

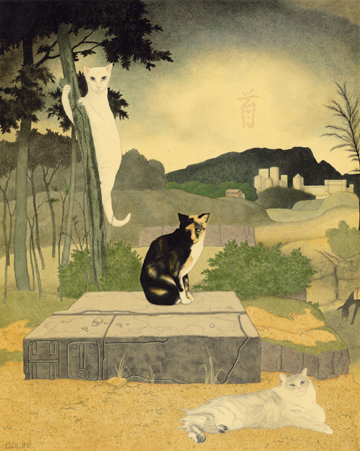

Hangmen, cockerels and cats share space with Roman soldiers, bishops and saints. Jokes are juxtaposed with powerful statements. In the "Death And The Bishop" the figure in the foreground, the Bishop, hugs a young naked boy while in the background Death waits with a wooden stake. The message, Colini says, "…is enjoy now, pay later. This is how they die, by the stake."

In a painting entitled "The Martyrdom of Unidentified Saint" the large, glowing goose in the foreground is Colini’s first wife. The smaller image of the martyr carrying the cross is the artist, himself and the message? Colini shrugs and laughs.

Colini, who paints on Masonite topped by gesso, peoples his art with familiars including himself, his cats and his hometown. Elements of his peripatetic life, his childhood, his beliefs (he is a Buddhist) and his omnipresent sense of humor are everywhere. Sly, humorous, downright funny and simultaneously breathtaking, his paintings are truly "ars fantastica."

Colini has painted for more than 60 years. He is well known in Europe and his paintings have been exhibited around the world but Colini knows how limited the exposure is, how few people will ever see the originals. So when this Renaissance man stumbled on giclée, it seemed like a perfect answer.

A highly skilled photographer and a former FORTRAN programmer, Colini is no stranger to technology. He wanted to use this emerging process to capture, preserve and reproduce some of his works of art – some of which have never been seen by the public.

"More people could see my art. More people could afford it and there would be more glory for Colin," says the town’s namesake. "The city would be seen all over the world."

Colini’s first try at giclée was disappointing as was his second. Then Lizza Fine Art Studios opened its doors in Tunkhannock, Pennsylvania in the fall of 2003.

The renovated roller rink is home to the first and only Cruse CS285 ST in the United States, the most technologically advanced, large format, high-resolution scanner in the world.

|

|

Studio owner Bob Lizza, a commissioned oil painter himself, says the Cruse was uniquely suited to reproducing Colini’s paintings. "Image capture is crucial to reproducing works of art," Lizza explains. "Tempera paintings are flat and high gloss. Normally, that would make them tough to light but lighting on the Cruse is fixed and the bed moves so the scanner never picks up any glare or distortion."

The Cruse CS285 ST is the first scanner in the world to target precision in all areas – focus, lighting, lens resolution, squareness of camera to subject and squareness of the digital back. Cruse Technical Representative Mike Lind says that the one area that really sets the scanner apart from all others is, "…the lens. It can see 90 line pairs. Normal lenses can see 20 line pairs in a millimeter – a line and space." Lind adds, "It’s the difference between painting with a brush and painting with a roller."

The Cruse CS285 ST is also able to resolve images that are only 8 microns apart. Taking advantage of the ultra-high resolution available through digital cameras, it uses a complex software algorithm to focus, eliminating human error and maximizing sharpness on all scans.

Once the image is captured it has to be matched to the original. Here, the practiced eye of the artist joins with the practical skill Lizza developed while working as a commercial designer for 18 years. "The trick is to match the original by looking at images on a computer monitor and managing colors that have been reduced to bits and bytes of data." Lizza stares intently at the screen as he mouses over a detail on one of Colini’s paintings. "Images in the original artwork – the vibrant red of an individual flower petal or the rich green in the eye of the trout look different on the computer monitor."

Here, too, Lizza complements his innate understanding of detail in the piece with technology. He uses a spectrophotometer, hardware and software designed to ensure the colors match. Lizza doesn’t want an approximate match so he takes one more step – one that addresses the difference between what the camera sees and what the human eye can see – the color gamut.

With a unique, proprietary process, Lizza studies and compares the tonality and the color of the giclée to the original. If there is any difference, like greens that are just a shade too yellow, Lizza adjusts the colors until the match between the scanned image and artwork is exact. Then it’s ready for printing.

The digital inkjet printer sitting in the production area of the studio uses ink jets smaller than a human hair. The spray rate is 4 million dots per second and the spray itself is so fine – 1.5 microns which is smaller than a red blood cell – that the droplets cannot be seen by the naked eye. It takes a 10X or 15X loop to see the black dots, the largest dots on the canvas or paper.

|

|

When the giclée is completed, the finished image is made up of close to 20 billion dots of saturated, water-based archival inks capable of producing a combination of 12 chromatic changes and more than 3 million colors. Marry these vibrant and rich colors with the continuous tone and stochastic screening created by the giclée printer and it’s easy to see why the giclées produced at Lizza Fine Art Studio make Colini smile.

"I was only 13 when I realized that painters die but paintings really don’t. Bob Lizza understands that." Colini pauses, then smiles. "He focuses on art. He is an artist." And, like Colini, Lizza is creating something that will last long after he and the oldest living surrealist die.

Note: Colini's work will be on view at Lizza Fine Art Studios, 155 Bridge St., Tunkhannock, PA on Sunday, July 11, 2004. A reception will be held from 2-5pm. More information may be obtained about Lizza's work at www.lizzafineart.com.

(Author/reporter Pat Muccigrosso lives in Lincoln University, PA.)