Profile: Susan Hope Fogel

By Raymond J. Steiner

ART TIMES Spring 2014

Susan Hope Fogel in her studio |

A LITTLE OVER ten years ago, Susan Hope Fogel (painting at the time as Susan Fogel Morris) had a solo exhibition during the months of September thru the beginning of November 2002 at the Museum of the Hudson Highlands at Kenridge Farm in Cornwall, New York. I visited the show for the purposes of a critique of the work and, although I did not have the opportunity for any "face-to-face" with Susan for any length of time (never easy at an opening), was quickly brought under the spell of her extraordinary talent evinced over and over in some 50 oils of florals, still lifes, landscapes, and portraits.

The distance of some hour and a quarter of driving between her studio/atelier and my study limited any subsequent get together, but we did occasionally meet now and then over the ensuing eleven years — over a cup of coffee, sometimes lunch, but mostly "on the run" if our paths happened to cross. Still, her work "hung in my mind" during the passing years (aided by one of her landscapes that graces my living room), and the idea of getting to really know the person behind the work for a profile in our pages has long been a-gestating. My long-held desire finally came to fruition this past December after she agreed to my visiting her studio/atelier in Warwick, New York.

The title of Susan's exhibit back in 2002 was "Painting the Light" and she has remained steadfast in doing just that, i.e. following a timeless tradition that culminated for "us" in the mid-eighteen-hundreds under the banner of "The French Barbizon School." Briefly stated, it was a long-held belief that "real" painting was a matter of capturing the play of light on the forms and colors of natural phenomena. The more we learned and observed how light revealed the world we live in, the "realer" our art would be — "realism" or "realistic" or "representational" art, therefore, would be the mainstay — so manifestly demonstrated in Susan's exhibit of "realistic" motifs.

Floral

Floral |

From the outset of her career in art, Susan assiduously set her mind and talents to the pursuit of such art, still termed "classical" to many, and for this writer, the only "genuine" art there is. In Susan's case, using the term "classical" is eminently apropos, since her basic art classes and subsequent teaching at the high school level led her on to the more rigorously formal schooling at The New York Academy of Art in New York City where painting from the cast was de rigueur before painting from the live model. Here, disegno (drawing) was the norm, adopted by the Italian Renaissance painters as the logical basis of art since it implies and involves not only the drawing (the hand) but also the mental formulation of the idea (the mind) — an idea largely ignored and pooh-poohed by many art academies and schools of today. Disegno — Draftsmanship — Drawing — is now held in low esteem by many moderns. Thankfully, artists such as Susan — those I call the "real" artists — adhere to the old art of drawing as a fundamental step in the process of becoming a painter, following Michelangelo's dictum that “…si dipigne col ciervello et non con le mani” (one paints with the brain and not [merely] with the hands).

Having mastered the skills of draftsmanship, Susan then concentrated on the role of light in realistic painting, attributing her interest and fascination to the influence of later teachers, especially that of John Philip Osborne, an instructor at the Ridgewood Art Institute in New Jersey who, she avers, "taught her to [develop] her painter's eyes". When one considers the difficulty in "understanding" the role of light on form and color, especially its ever-changing presence and effect, it is perhaps easier to understand the dismissal of classical training by both "modern" artists and the numerous middlemen involved in the artworld of today. Hard enough to understand the nature of matter let alone the "whys" of its shape and color! Once mastered, if not fully understood (we are still learning), we can then call ourselves "master" and can feel ourselves akin to the great painters of the past who have defied the march of time and the constant parade of "isms" that tout the end of skill and beauty, which seem to perennially crop up. Sometimes, I suppose, it is tempting to forego the discipline and just spread a lot of paint around and claim "mastery" if it sells.

Male Nude |

Not so with this artist. There is little doubt in my mind that Susan Hope Fogel is a modern-day master and will be so considered far into the future, comfortably finding her niche among the "greats". I've felt this since I critiqued her first show, telling my readers back then that if they subscribed to Bernard Berenson's idea that art ought to be "life enhancing" then a trip to see her "Painting the Light" exhibit would "go a long way toward lifting your spirits". Now, after nearly a dozen years and just recently spending an afternoon with her at her studio/atelier, I see that I have barely scratched the surface of this remarkable artist. I quickly learned that her attempts to "catch the light" go far deeper than "trapping" the momentary effect of light on a given arrangement of jars or flowers, a tree, or a person.

Sitting in Susan's studio/atelier or kitchen, walking around with her in the lovely, landscaped environs of her home in the Hudson Valley, and —most of all — listening to her slowly unveil her "soul", soon led me to her real "light source". Like most serious artists I have met over the years, Susan was at first somewhat hesitant to speak about her art or her ultimate creative source (I've long learned to distrust the glib artist who speaks more of their "success" — i.e., making sales — than about their "art"). Unsure of the stability and endurance of their personal "urquell", many true artists tend to be protective of their inner source of creativity, some even going to great lengths to secure their "inner sanctums" within their outer coats or studios, from easy access or intrusion. The truth is, we have not yet uncovered or "explained" creativity or its inner springs. Humans, some humans, seem to possess creativity, but neither they nor the "scientists" seem to be able to explain it — and since it's so elusive, why jeopardize it by speaking about it? Maybe the spring might "dry up".

However, if she did not at first speak "freely" about her inner creative source, her home, her studio/atelier, her grounds, her very "self", all spoke of her sense of balancing her (or, more properly, the universe's) energies. She was, to me, a living example of someone "divinely inspired". During the Renaissance and before, thinkers spoke of artists (real artists) as being "divinely inspired", meaning that they were "inspired", literally "breathed into", by God. It is, ultimately this light that inspires the painting, "natural" light being, as in Plato's world, a mere copy of the original.

Serenity along the Appalachian Trail |

Serious artists have long known that this inner, inspired — "divine" if you will — light that lies at the bottom of creativity is utterly erratic, elusive, indefinable, volatile, temperamental — even untrustworthy at times. They also know that instructors can only teach would-be artists the mechanics, the technical aspects, the "rules" of the best way to make a picture…the creative urge can never be "infused", no matter how good or thorough a teacher is. Artists are truly born, not made. "Rules" are carefully inculcated and learned — hence the long internship of becoming a classical painter. Still, no matter how strict, no matter how exhaustive, no matter how taught, the "rules" are mere "harnesses" on an unpredictable source. In another context — but one that I feel is illustrative — is the observation made by the Hasidic philosopher, Martin Buber, that "revelation is [never] a formulation of Law. It is only through man in his self-contradiction that revelation becomes legislation." Our "self-contradiction" stems from our inability to fathom the "revelation" of our own mysterious creative sources and it is this uncertainty that leads to "legislation", i.e. the rules surrounding the art of painting. If nothing else, the rules at least afford a sense of confidence and stability if not inspiration.

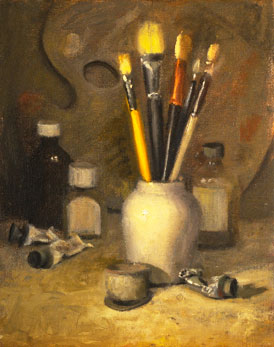

That Susan is aware of this conundrum is, as I said, "readable" in her art, her surroundings, and her "self". That she has mastered the "laws" of painting, is manifestly obvious in her work. That observation was reinforced by visiting her home with a statue of Quan Yin in her kitchen window, overlooking her landscaped gardens which follow the dictates of Feng Shui, a 3000 year old Chinese system of balancing the Feng and Shui, literally 'Wind' and 'Water' but, figuratively all natural forces — a way of imposing "good" order in one's life and environs. Her studio/atelier, likewise, is also "ordered" but in a somewhat Spartan fashion. She prefers natural light to "man-made" illumination (hence most of her landscapes are done in plein air, many in her exquisitely landscaped 'backyard') and her interior decoration of both her studio/atelier and her home practical and disciplined rather than showy. As in her art, so in her living/working space, Susan makes clear her reverence and respect for nature's mystery and power. Her composure, her grace, her speech, and her confident manner all emphasize and confirm this outer and inner balance.

|

Returning to that "divine" as opposed to "natural" light — and of Plato's ordering of the universe into a world of "becoming" (i.e. here, our world) and an "ideal" world ("heaven") — its very "divinity" makes it even more "unknowable" than that ever-shifting earthly light that painters have to contend with every time they pursue "realism". To my eyes, one of the hints of "divine light" appear in the subtle highlights with which good artists are able to enhance their "realisms" with verisimilitude. The painting not only is believable, to the attentive eye it is magically alive! It breathes, it literally "sparkles", it's tangibly there. This "divine-made-natural" light appears again and again in Susan's work, continually attesting to her subtle mastery of her medium. One can almost "see" in this or that particular highlight on a flower's petal or glancing off a hint of water in a landscape, the seed — or source — of the final work — a microcosm, so to speak, of the "subject" contained in the macrocosm of "rules" informing the painting.

Near the end of my interview with Susan, shortly before I left, she pulled out a canvas that had been tucked away amongst others, quite literally out of sight on a low shelf against a back wall. Along with it, she pulled another canvas, likewise tucked away, with, like its partner, its narrow left edge the only part facing the viewer. This second canvas, an obvious depiction of a shipwreck, she placed on a nearby standing easel, and the first, set on the floor against the leg of the easel. I was taken aback, almost feeling a privilege since it appeared as if they were only being shown to me. Why were they hidden? Or at least stored out of sight? Both paintings were startling, almost threatening, the second one being revealed, the "Shipwreck", vivid in its depiction. One could readily see the years of honed draftsmanship that evoked a sense of the palpable fear that seemed to be coming from those doomed voyagers. I could hear their cries for help.

It was when I turned my attention to the other painting, the one at the foot of the easel, that I realized that Susan was silent throughout this wordless process. There was "show" but no "tell". More on that second painting in a moment, but when I turned from the shipwreck to Susan's silent face I had the strange illusion that it was she and not the voyagers whose cries I heard — else how could they be so believable? There was tension — even anger — in her face and, feeling that this "private" showing was for my eyes only, I was reluctant to break the silence by asking questions. Perhaps sensing my inquisitive look (my Profile interviews are often uniformly and uncomfortably "inquisitive" — so I've been often told — since I'm trying to get into my subjects' heads, delve into their souls), she softened her rather tense expression and said, "That was a response to a difficult situation". I held back from further probing and, lifting the other painting from the floor, was treated to such a gamut of reactions and feelings when I held it before me and looked at it, that I found myself somewhat dumbfounded.

Warrior |

First of all, there was no discernible motif, no "subject" — the only such work of Susan's oeuvre that I had yet seen. It was, in brief, a simple(?) "explosion" of light. I do not recall any distinctive color or subject — it was as if whatever was going to be depicted was obliterated by the light. I could not (and still cannot) call it an "abstraction" and I'm still not sure if "explosion" is the right word to use here. It was certainly disconcerting, to say the least — and continues to puzzle, intrigue, and baffle me. It still lingers vividly in my mind though I cannot say precisely why. When I glanced at Susan, her face showed some consternation but not exactly the "fear" I had read before. All I recall her saying, was: "Another difficult situation."

OK. But what was her painting "saying"? To me? Still thinking about its "message" I continued to feel that, as profound as I felt it to be, I could come away with no words — just the image of an "explosion" of light. It was, in truth, ineffable. Then I allowed myself to explore that thought; was not — is not — "ineffable" the very word that the ancients used when attempting to speak of (or paint) the "divine" inspiration?

Ineffable. Unspeakable. A Mystery. An Enigma.

So, what was I holding in my hands?

My only "rational" explanation was that I was seeing an enlargement or "blow-up" of one of Susan's highlights taken from some other "realistic" painting. Was it? Was it her rendition of the ultimate source of her paintings? Of all paintings? A "picture" of The Light? Of the Source? Surely it emitted a feeling of Power. Of turmoil. Of awe.

"Does it have a title?" I inquired in an email a few days later.

"I have referred to it as 'Warrior'," she wrote back.

Was it, then, an attempt to confront her Divine Spark? Her "soul"?

If I am in any way close to the 'truth', then "Warrior" stands in a very special relation to the totality of Susan's work. Since she is a classical realist, where do we place this abstract in amongst all those florals, landscapes, still lifes or portraits? At the beginning — the Source? At the pinnacle — the Culmination? Or prominently displayed at every step of her life-long progress as a fine artist?

I have, in the past, used the analogy of Icarus when speaking of (some) artists; however, with Susan Hope Fogel, I believe she is the first one I've come to know who not only reached the light, but has also returned safely back to earth to share her revelation with us through her paintings.

Warrior, indeed!

(Susan Hope Fogel — artist, teacher — and, yes, warrior — (www.susanhopefogel.com) has ongoing classes and workshops in drawing and floral/still life in her Warwick Atelier (warwickatelier@aol.com) as well as plein air painting classes in Warwick, Cape Cod, Tuscany and Ireland — all according to the classical teaching principles of painting and drawing in the representational style. Go to The Warwick Atelier on Facebook to see posts of upcoming events.)