Speak Out: “A State of Art: Maine’s Influence on African-American Artists”

By Leigh Donaldson

ART TIMES Spring 2013

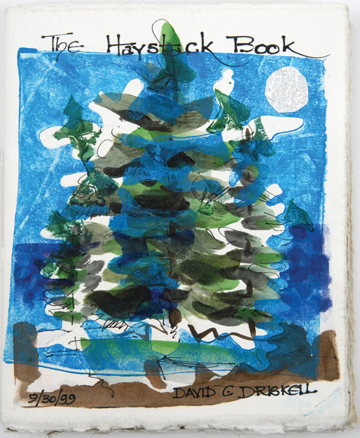

The Haystack Book David C. Driskell The Haystack Book David C. Driskell |

“Even during the most difficult periods of African-American history, the natural world held potential to be a source of refuge, sustenance and uncompromised beauty”, writes editor, Camille T. Dungy, in “Black Nature: Four Centuries of African-American Nature Poetry”. Though Dungy was primarily referring to how black poets were influenced by their physical environment, the same can be said of visual artists of color.

Maine may not be the first place that comes to mind when thinking of African-American artists. Names such as Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, John Marin, Rockwell Kent and the Wyeth family are more commonly viewed as prominent in Maine art culture. Yet, despite having a black population of less than two percent, the Pine Tree State has been a spiritual home for artists for many decades.

Captured in East Africa as a child, Pedro Tovookan Parris was captured in a night attack by a neighboring tribe, scattering his family, including three brothers and his grandmother. Later, he was sold during the 1830s to Portuguese slave traders in Zanzibar and transported to Rio de Janeiro on the American brig, Porpoise, captained by Cyrus Libby of Scarborough. Ultimately arriving to Maine, Pedro (meaning “to run away” in his native tongue) was adopted by the Parris family of Virgil D. Parris, then the state’s US Marshal. During his life there, he produced an autobiographical work of art in pencil, ink and watercolor on cotton linen, depicting his progression from captivity to his life as a free man. This provocative piece, now preserved by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, depicts an emotional continuum from slavery to freedom: troops marching into Rio de Janeiro, the US frigate Raritan sailing north, a view of the gold dome of Boston’s State House on Beacon Hill and, finally, a tableau of the Parris family farm in Paris, Maine. Pedro Tovookan Parris now rests near the Parris family plot at the knoll cemetery on Paris Hill.

Since the 19th century, African-American artists established creative roots throughout New England, including Joshua Johnston, Robert Scott Duncanson, Edward Mitchell Bannister, Edmonia Lewis and Henry Ossawa Tanner, who worked under much more difficult circumstances than their white counterparts, lacking receptive academies, museums and patrons, as well as social and economic opportunities.

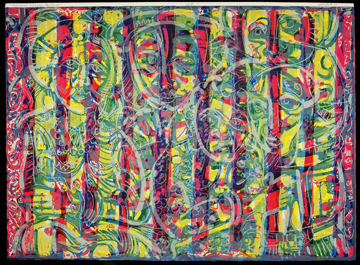

Ancestral Images by David C. Driskoll Ancestral Images by David C. Driskoll |

There is considerable evidence that many black artists lived and worked in Maine, regardless of hardships over many decades. For example, in the 1920s painter Palmer Hayden attended a summer art colony in Boothbay Harbor, offering to work as a cook in exchange for art lessons. Hayden had grown up in Widewater, Virginia, where he drew pictures of boats plying the Potomac River. Maine’s landscape also inspired him and he painted several marinescapes, one of which, The Schooner, won him the William E. Harmon Foundation’s first award for Distinguished Achievement Among Negroes leading to his art study in Paris and his becoming a leading artists during the Harlem Renaissance. His love of ocean vistas and nautical subjects led to a series of paintings he created on a trip to Brittany, a rugged peninsula of northwest France that may have reminded him of Maine. Of his sojourn in Maine, he once remarked, “That was a real turning point for me…I began to realize things and make connections about everything.”

There is probably no art school in Maine that has had as profound effect on artists of color as the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. Located in the town of Skowhegan (its named derived from the local Native American word Skowhegan, which means “watching place for fish”, the falls of the nearby Kennebec River having been a favorite for salmon), the school, since 1946, has sustained summer residency programs where race posed no barrier to learning and creativity and African Americans have played a prominent role in its history and development.

It was part of the mandate of Willard Cummings, a New England portrait painter and one of the school’s founders to reach out to black students and bring them to Skowhegan. To do so, he approached Howard University and between 1947 and 1974, almost 30 of its students attended Skowhegan, most receiving full scholarships. Indeed, the list of African-Americans who have attended the school as students (called participants), visiting artists and artists in residence is expansive: Romare Beardon, Elizabeth Catlett, Gregory Coates, David Driskell, Mel Edwards, David Hammons, bell hooks, Jacob Lawrence, Glen Ligon, Whitfield Lovell, Lorraine O’Grady, Howardena Pindell, Adrian Piper, Martin Puryear, Alison Saar, Betye Saar, Nari Ward, Carrie Mae Weems, and Fred Wilson, among many others. No doubt, in appreciation of the schools’ welcoming of black artists, Jacob Lawrence’s widow, Gwendolyn, established a fellowship in her husband’s name and donated the bulk of his extensive collection of art books to the school’s library. In the 1990s Camille and Bill Cosby endowed a fellowship specifically for African-American artists, which has, to date, helped more than 20 students.

Skowhegan’s 300-acre campus remains unassuming. A small sign along old White Schoolhouse Road leads toward hills and pine forest, close to the former mill town from which the school took its name. At first sight, with its rustic 19th century wooden buildings and studios, it resembles the chicken farm it once was rather than art school, according to New York Times reporter Scott Southerland. Most importantly, the school has maintained its original vision, that is, a school governed by artists for artists, a place that encourages creative expression free from marketplace expectations, popular critics and academia.

From the beginning, Skowhegan emphasized skill over theory and promoted keeping an open mind about artistic styles. Co-founder and painter Henry Varnum Poor wrote in one of the school’s earliest bulletins: “Painting in America is now a very fluid and experimental and rapidly changing period…But, in whatever direction painting swings, it always returns to reality as the one vital, original and creative source.”

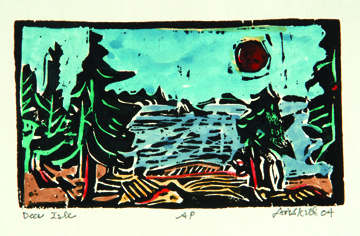

Deer Island by David C. Driskell Deer Island by David C. Driskell |

David Driskell, whose career as an internationally recognized art teacher, curator, historian, collector and writer spans more than 47 years, was a 1953 student participant at Skowhegan. During the summer, the first thing you notice when you drive up toward his studio in Falmouth, Maine, is a quarter acre of thriving corn, potatoes, tomatoes, beans, collard greens, cucumbers, alongside brilliant flower beds. Referring to his series of paintings that he created during his first summer in Falmouth, called “The Pines of Falmouth”, he states: “I was taken with the beauty of the landscape, what I call the romance of the pines, the way they flow and move in and out, when the wind blows; they create their own kind of lively world.” He designed his house in the early 1960s to look up at the trees from his windows. It can be said that the house was actually built and designed out of visions of these towering trees that are now so personal to him to the extent that he has given them a human dimension.

In “ David Driskell: Search of the Creative Truth”, a video produced, directed by Richard Kane, sponsored by the Union of Maine Visual Artists as part of the Maine Masters Project, the painter, a Georgia native, recalls his upbringing as poor in the western Appalachian region of North Carolina and the viewer can easily imagine that he is as proud of his gardens and nature as he is of his paintings. “The Maine pine has been a source in my work since I came here…It’s not just the greens or what I discern as the blue. I have invented color.” Indeed, his thesis in graduate school at Catholic University of America was about the pine tree as a symbol of eternity, how anything that is evergreen, in particular cedar and pines, has been used as a representation of everlasting life.

While he was teaching at a southern college in the South, Driskell turned away from painting people because the racially charged struggles were so ugly to him. This creative crisis apparently occurred after he painted “Behold Thy Son” in 1956, based on the Emmett Till killing. According to Driskell, it was part of his process of emotionally navigating through the difficulty of the Civil Rights Movement; the crises in Alabama during the 1950s, the Klan coming to campuses, the cross burnings. Driskell recalls how these horrific events affected him at the time and how he said to himself: “I can’t paint people any more. They’re not symbols of beauty any more…I’m going to nature…the trees, they’re so forgiving, they’re so loving, they’re so caring. And, so, I started painting all these trees and they became part and parcel of what I did.”

Not only has Maine captured the imagination of black artists throughout the world, but has a notable homegrown community of artists of color, including illustrator and author Ashley Bryan, now 89, who came to Skowhegan in its inaugural year. A recipient of honors including the Coretta Scott King Book Award, Bryan first witnessed Maine’s Little Cranberry Island on a trip to Acadia National Park in the 1940s and has since resided on the island village of Islesford, Maine.

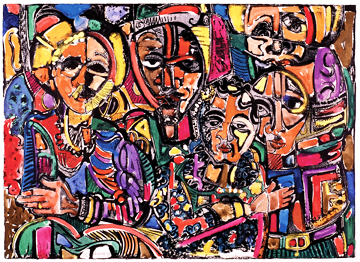

Spirits Watching by David C. Driskell Spirits Watching by David C. Driskell |

Born during the Great Depression, he took free art classes funded through the federal government’s Works Progress Administration. After attending the Cooper Union School of Art & Engineering, he served in a US Army black battalion where he saw action during the invasion of Normandy on Omaha Beach. Later, he would earn a degree in philosophy at Columbia University and pursue painting in southern France on a GI Bill going on to receive a Fulbright fellowship to study in Germany. From 1974 to 1988, he chaired the art department at Dartmouth College.

Despite, or perhaps because of his worldly success, Bryan has stated that his Skowhegan experience in particular and being a resident and active member of Maine’s increasingly diverse artistic community, is one of the most profound influences on his art. “Skowhegan reinforced my belief that what matters most is what you do now and that art is about seeking out meaning in life beyond negative things like war,” the artist expressed to me in a 2008 telephone interview. “Nobody puts obstacles in your way when you pick up a paint brush.”

In this vein, Bryan appears to have little patience for the notion of so-called 'black art’, seeing its pursuit essentially as a “waste of creative energy”. Again, his work is more often informed by the natural world. In a 2005 interview about the publication of his children’s book, “Beautiful Blackbird” with the Maine Sunday Telegram, Bryan stated: “I was raised in New York City, but I’ve always known I was a country boy at heart. I used to go to the park and try to find a place where I could see no buildings.”

Many artists of color past and present who have studied, lived and worked in Maine echo much of this sentiment that being an artist trumps being African-American, that natural beauty is essential to their craft.

“The most powerful introspective times of my life have been at Skowhegan and in Maine”, stated Alison Saar, daughter of the renowned African-American artist Betye Saar and art conservationist Richard Saar. The younger Saar often returns to the state and reflects on how her experience there has deepened her awareness of the power of the elements. “There’s something about the quality of the air, the northern lights — it’s magical”, said Saar whose background in African, Latin-American and Caribbean art is noticeably imprinted within her own work, lending a unique sense of both spiritual and cultural diversity.

Daniel Minter, an award-winning children’s book author and illustrator is a long-time Portland, Maine resident. Born in Georgia, he is largely self-taught, but trained at the Institute of Atlanta. According to his website, he has exhibited his paintings and sculpture at galleries and museums such as the Seattle Art Museum, Bates College in Maine and at the Meridian International Center. He is also founding director and vice-president of Maine Freedom Trails, Inc. and created the distinctive plinth-style markers that identify significant sites related to the abolitionist movement and Underground Railroad activity throughout the city of Portland, Maine. He also designed the US postage commemorative stamps for Kwanzaa in both 2004 and 2011.

Describing Minter’s art, ethnic studies professor and historian, Elizabeth Harding writes: “This is the work of the guardian, the interpreter, the one-who-watches-at-the-gate. Giving us back the ground we grew out of…the fertile place…source of our sweetness and struggle…All Africa in diaspora…stony cities and the pushed rhythm of the fields. Oceans. Winds. Our new world routes. Our new world wisdom. Our strength. Our salt.”

For all the visual artists who have lived and worked in the state of Maine, there is clearly a sense that the place itself has afforded them a full range of feelings, concepts and emotions, including race identity and heritage, that shapes their craft. For any artist, nature can be a refuge, and escape, but, perhaps, most importantly, a starting point.

(Leigh Donaldson’s writing has appeared in print and online publications such as the The Montreal Review, American Legacy Magazine, American Songwriter Magazine, Portland Monthly Magazine, Maine Food & Lifestyle Magazine, and “Maine’s Visible Black History” (Tilbury House Publishers). His book about the antebellum African-American Press in the Northeast will be published by McFarland & Co. Publishers in 2014.)