Theatre: The Tricky Limits of Color-Blind and Gender-Blind Casting

By Wendy Caster

ART TIMES April 2016 online

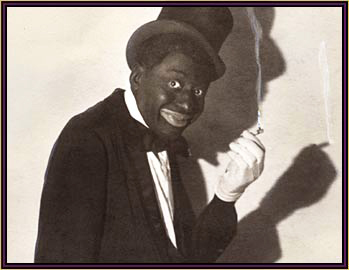

African-American singer-comedian Bert Williams in blackface |

Once upon a time, boys played the women’s roles in Shakespeare’s plays. Once upon a different time, Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor performed in blackface to great acclaim, and some brilliant black performers had to hide behind blackface to be accepted by white audiences. (African-American comedian-mime-singer Bert Williams, 1874-1922, once said, "A black face, run-down shoes and elbow-out make-up give me a place to hide. The real Bert Williams is crouched deep down inside the coon who sings the songs and tells the stories.") As recently as 1990, white actors played Othello with darkened skin.

And once upon today, right now, multicultural casting has burst open, with Latino and African-American founding fathers in Hamilton, two upcoming female Petrucchios (The Taming of the Shrew) in New York alone, and black actors recently cast as the Phantom ( Phantom of the Opera) and Jean Val Jean (Les Mis) on Broadway. While this form of casting is the polar opposite of blackface, it is not without controversy. “African-Americans wouldn’t have had that job, lived in that place,” people say on theatre chat boards and elsewhere. And they often add, “Why not an all-white Raisin in the Sun?”

Meanwhile, a recent casting notice for Hamilton specifying “non-white performers” angered many actors and went afoul of the union and possibly New York City law. According to CNN.com, civil rights attorney Randolph McLaughlin said, “You cannot advertise showing that you have a preference for one racial group over another. As an artistic question – sure, he [Lin-Manuel Miranda] can cast whomever he wants to cast – but he has to give every actor eligible for the role an opportunity to try.”

If ever there was a situation without an absolute correct answer, it is this one. People of color are likely to see it differently than people of no color; women differently than men; gay people differently than straight people; cispeople differently than transpeople; and so on—not to mention individual differences in point of view. I can’t imagine a solution that would please everyone, but that’s par for the course in human matters.

Harriet Walter in Julius Caesar (Photo: Helen Maybanks) |

There are two categories of discussion relevant here: artistic and pragmatic. Take all-female productions of Shakespeare, which are quite fashionable these days. Artistically, female casts let us see the plays from a new angle. A woman Petrucchio underlines the stupidity of defined sex roles. Women Hamlets and Macbeths allow us to questions many of our assumptions about behavior. And, pragmatically, female casts give jobs to women who may have spent years playing supporting roles or not working much at all. Throughout the history of theatre (and movies and TV), there have always been significantly more roles for males than females. Why shouldn’t women get to flex their dramatic muscles?

It’s interesting to me that many creative people see cross-gender casting as a one-way street. For example, both Passion, as directed by John Doyle, and Peter and the Starcatcher, as directed by Roger Rees and Alex Timbers, had few women in their casts. Many performers played multiple roles, including men playing women. But why couldn’t more women be cast? Women can play soldiers and pirates just as well as men can play mistresses and nannies. But the habit is to hire men, and, yes, mostly white men.

Nontraditional casting sometimes changes a play tremendously—and sometimes it doesn’t. I’ve seen a few female pairs of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in Stoppard’s great play; their gender ultimately didn’t matter. On the other hand, in Caryl Churchill’s Cloud Nine, gender is everything. Having males play females and females play males undercuts stereotypical assumptions, as the brilliant author Churchill knew it would. After all, why should having male sex organs deny you the right to like dolls? Why should having breasts require you to hide any athletic prowess you may possess? (The play was groundbreaking in the 1970s, when it was written; while its points are more familiar now, it remains sadly relevant.)

Audra McDonald on the poster for 110 in the Shade |

Similarly, color-blind casting may change a play—or not. James Earl Jones was the best King Lear I ever saw. His color was irrelevant—as was Audra McDonald’s in 110 in the Shade. In Hamilton, on the other hand, the performers’ races are completely relevant, as Lin-Manuel Miranda expands the history of the United States to include all of its citizens.

And in all of these cases, we get to see fabulous performers we might otherwise miss. We all benefit.

Nontraditional casting can change the world. It has been said that Barak Obama might not be president if various movies and TV shows (e.g., 24) hadn’t accustomed voters to the idea of an African-American leader. Similarly, people who see an all-female Julius Caesar are exposed to women who are political and powerful.

So, what about that all-white Raisin in the Sun? I think it’s a pointless idea, since the show is specifically about blackness. Yet I love the idea of Japanese and African productions of Fiddler on the Roof, which is specifically about Jewishness. Still, Raisin in the Sun is much more recent and reflects ongoing issues, while Fiddler is older and has almost a mythic feel to it.

But here’s the thing: if a director should have a vision that includes an all-white cast, and finds backing for the production, and gets permission from Lorraine Hansberry’s estate, then, who knows? —perhaps the all-white cast will tell us something new and important about Raisin. I doubt it. (Also, the production would be taking roles away from black actors.) But while it’s unlikely anyone would want to take on the negative press, picket lines, and even death threats that might ensue, an all-white Raisin in the Sun would not be, by definition, wrong or evil. It’s important for artists to follow their hearts, even to weird places.

As for the quote above that Hamilton should be obligated “to give every actor eligible for the role an opportunity to try,” what does “eligible” mean? Should women be allowed to audition? People who are older, younger, taller, shorter? In making this comment, McLaughlin reveals that he sees race to be less of a differentiator than gender, which is interesting but not surprising.

According to BroadwayWorld.com, last November Lin-Manuel Miranda was asked if he would consider female actors in the roles of America's Founding Fathers. He talked about the differences in men and women’s voices, and sounded disappointingly against the idea. Then he added, "That being said, no one's voice is set in high school. So I'm totally open to women playing founding fathers once this goes into the world. I can't wait to see kick-ass women Jeffersons and kickass women Hamiltons once this gets to schools.”

Me neither.

( Wendy Caster is an award-winning writer living in New York City. Her reviews appear regularly on the blog Show Showdown. Her short plays You Look Just Like Him and The Morning After were performed as part of Estrogenius festivals. Her published works include short stories, essays, and one book. )