Theatre: When Less is More: The 90-Minute Play

By Wendy Caster

arttimes online July 2016

The Flick (Playwrights Horizons production). |

What accounts for the rise of the intermissionless 90-minute play? A prevalent theory points to the shrinking attention spans of a population inundated 24/7 with news, information, entertainment, and gossip.

I think this theory relies on knee-jerk conventional wisdom and ignores the huge success of, oh, Hamilton, which runs 2:45; The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, which also runs 2:45; and 2014’s Pulitzer Prize-winning drama, The Flick, which runs a quiet and plotless three hours; all three have intermissions.

But not every story needs 165 minutes to be told. And there is something deeply rewarding about being 100% invested, without interruption, in a sleekly written piece pared down to its essentials. Take, for example, John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt (another Pulitzer winner). In a gripping and grimly entertaining 90 minutes, he covers responsibility, trust, hierarchies, fierce mother love, and, yes, doubt. Eugene O’Neill might have taken over three hours to tell the same story, with no value added. (And Shanley lets the audience get home in time for a good night’s sleep.)

Speaking of O’Neill: When I was in college, I directed a scene from his Moon for the Misbegotten. We had a time limit, and the scene was considerably longer. I didn’t want to just hack a chunk out of it, so I decided to see what I could gently remove without hurting the plotline, characterizations, or emotions. With surprisingly little effort, I cut the scene down to size; I just removed the most egregious repetitions. Of course, there is more than one way to interpret this anecdote. It’s possible I damaged the scene in ways I didn’t recognize. It’s possible that I just have a gift for editing. But it’s also possible (and this is the interpretation I subscribe to) that Eugene O’Neill overwrote like mad.

Doubt (original cast), starring Brian F. O'Byrne and Cherry Jones. Photo by Joan Marcus. |

And then there’s A Streetcar Named Desire. It’s one of my all-time favorite plays. I see it whenever I can. But damn, the last section could use some cutting.

During the period when O’Neill and Williams were writing, longer plays were the norm, often with two intermissions. If they were writing now, would they feel pressure to take another look, to cut out a little chaff so that the audience could better enjoy the wheat?

I cannot transport myself into the mindset of 1950’s theatre-goers. How different to live in a world with little TV, where you had to leave the house to see a movie, where performance wasn’t always a click away. It’s possible (likely?) that people’s brains perceived the world at a different pace than ours do now. Theatre must have provided a special occasion I cannot fully comprehend. But I imagine it felt wonderful to luxuriate in three-hour shows. Now, any minute we spend watching one show/movie/play, we’re not watching a million others. The entertainment/art market is swamped. It’s competitive out there.

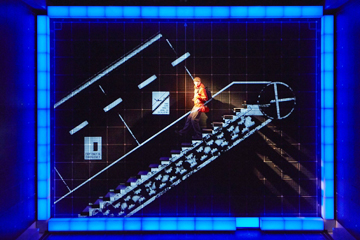

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time (original London cast). Photo by Brinkhoff Moegenburg |

I suspect that the breath-taking efficiency of the best TV writing has also changed the way many (most?) of us perceive the performing arts. Shows such as The Wire, Game of Thrones, Six Feet Under, Fargo, and many others juggle multiple story lines in great detail with vivid characterizations and driving suspense. While theatre may sometimes aim deeper where TV aims wider, the same techniques still reign: the revealing moment, the exact right detail, behavior that exposes more than words ever could.

While the growing trend in streamlined writing doesn’t demand 90-minute plays, it does demand that longer plays earn their extra minutes or hours. Curious Incident does so by utilizing vivid, deeply imaginative theatricality to tell a story both with and without words. August: Osage County did it by being so damned compelling that every minute was a treat. Marathons such as Nicholas Nickleby, Tom Stoppard’s Coast of Utopia, John Guare’s Lydie Breeze, and Mac Rogers’ Honeycomb Trilogy do it by providing epic entertainment, with entire lives unfolding before your eyes. They are special events.

A friend of mine, who sees many shows a year, recently wrote on Facebook,

“90 minutes, no intermission” — the most glorious words in the English language!

I agree.

And when a show does run longer, and truly needs to, and uses every moment splendidly—well, that’s pretty darn glorious too.

( Wendy Caster is an award-winning writer living in New York City. Her reviews appear regularly on the blog Show Showdown. Her short plays You Look Just Like Him and The Morning After were performed as part of Estrogenius festivals. Her published works include short stories, essays, and one book. )