Art Essay: THE HABSBURGS: A New Fashion on the Art and Culture Scene?

By Eva Jana Siroka

ART TIMES online August 2015

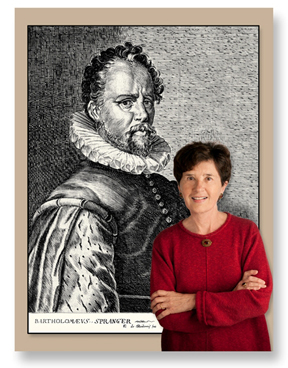

Eva J. Siroka and Bartholomaeus Spranger (engraving by E. de Boulonois; property of the author) Photo: Image Arts, Princeton, NJ |

Imperial Vienna. The city of my dreams. It was so close, and yet so far! In June 1965, my family and I said goodbye to our native land on the grounds of Devín Castle, perched high over the military zone between former Czechoslovakia and Austria. Across the Danube, less than 40 miles from the barbed wire fence, stood the heart and soul of the former Habsburg Empire. Since then, I have visited Vienna a number of times, crossing the now open border to my native Bratislava, each time with less trepidation. After arriving in New York and registering for my high school classes in the fall, I was encouraged to choose a profession different from my father's. "In the United States, women don't need to take masculine jobs," the principal informed my parents. I wanted to be a civil engineer, but becoming an art teacher was a more fitting choice for a young woman. The following spring, my art class painting showing New York's skyline represented my school at a Lever Brother House art exhibit in New York. But my heart was in the multifaceted culture of the Habsburg Empire, which swallowed my native land for centuries.

After my university assignments were done, I turned to my father's history and art books, at a time when most of my classmates hardly knew the location of Prague or Vienna. I sat in my German literature class, helping my classmates with basic grammar rules, disappointed that none of my art history courses covered the art of Central Europe. Italy was the rage then as it was in the sixteenth century, when the art of the Renaissance had spread as far as the Baltic Sea. Not until Princeton was I able to follow my interests and crisscross Europe's museums and institutions for my graduate work. Fast forward to 2015. Locations: Minneapolis, Atlanta, and Houston. A fabulous traveling exhibition, Habsburg Splendor: Masterpieces from Vienna's Imperial Collections at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, not seen since the end of the last war, is broadening our cultural experience through January 2016. Some one hundred objects from the imperial collection, priceless works of art and artifacts attest to the glory of a family that invented a line of ancestry reaching past ancient Rome to the Trojans in order to compete with Europe's important royal families. Aside from grand masterpieces by Titian, Rubens, and Velasquez vying for attention with coats of armor, weapons, costumes, and even a ceremonial carriage, I paused over the campaign uniform of Franz Joseph I. In it, the longest reigning Habsburg emperor spent countless hours at his desk to keep his crumbling empire from breaking into smaller multinational groups from which my native Czechoslovakia arose from ashes in 1918. When I now claim to have been born in that political entity, I'm reminded that it no longer exists.

If the Habsburg Splendor were not enough, it followed on the heels of an earlier, and even more astounding exhibition ― as far as the choice of the subject is concerned ― at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Bartholomeus Spranger, the Flemish-born painter who arrived in 1580 at the newly established capital of the Holy Roman Empire, was one of a number of foreign artists who assembled in Prague because of their sought-after training in Italy. After working briefly for Emperor Maximilian II, Spranger spent some seventeen years in the private chambers of his son and successor, Rudolf II Habsburg, painting in the castle studio. Open to a privileged few and closely supervised by the young emperor, Spranger willingly catered to his patron's exotic taste by producing mythological compositions with frolicking nudes. Considering more than five centuries of Habsburg rule, it struck me as odd that a painting by Correggio which had never previously left Vienna, Jupiter and Io, was selected to grace the catalog's title page accompanying the Habsburg Splendor, now traveling to Houston. As one of four Loves of Jupiter, Rudolf wasted no effort or money to own this and the remaining three paintings. Given the Habsburg's pride in ancestry, why not select the medal depicting forty-one rulers dating back to times immemorial for the cover, even if some may have been invented? New York's Bartholomeus Spranger: Splendor and Eroticism in Imperial Prague, with its catalog by Sally Metzler for the first major exhibition on the artist, is a welcome introduction to a master who had been labeled for too long as painter of erotica. Along the way, one also glimpses a few objects from Rudolf II Kunstkammer, the emperor's chambers of wonders, an interesting collection of items that today would belong to a natural history or science museum. In his New York Times review of the exhibition, Ken Johnson aptly summarizes Rudof's patronage: "After establishing his court in Prague, Rudolf II gathered about him a glittering entourage of artists, intellectuals, scientists, quacks and charlatans. An exceptionally erudite, psychologically fragile libertine, Rudolf was especially drawn to occult studies like alchemy, astrology and the kabbalah and it’s in light of those interests that Spranger’s erotically provocative mythic images were understood by the initiated."

In My Life with Berti Spranger, an illustrated historical novel that touches on the famous artist writing his memoir, Pieter Van de Graeff, a Dutch art dealer who discovers it in Vienna, becomes uncertain as to what to do with the precious manuscript. "Spranger conversed with God, begging His forgiveness [for his sins]. But he never knew about the telephone, the Internet, messaging, social websites, and the crazy times we live in now, and how things go viral." Four hundred years after Spranger's and Rudolf's deaths, one should perhaps look at Spranger's paintings with erotic subjects and take them for what they were and still are, and drop the erudite discussion. While the eagle in Spranger's Jupiter and Antiope, painted for Rudolf II, is an obvious symbol of the emperor and the lands he governed, Antiope's hand creeping up the satyr's thigh summarizes the meaning of this painting without further ado. After all, it was this painting that was chosen to advertise the Met exhibition in the New York Times. Ultimately, the two recent exhibitions shed a much welcome new light on the patronage of a celebrated European noble house. Perhaps now the 'Habsburgs' may even become a common name in North American households as we watch yet another BBC program on Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn, and the Tudors. Imperial Vienna, at our doorsteps.

Eva Jana Siroka, an art historian and artist born in Bratislava, Slovakia, received her doctorate at Princeton University. A Renaissance scholar with interest in princely patronage, especially Rudolfine Prague, she has been drawn to Spranger's art for decades. My Life with Berti Spranger (2015) is an illustrated historical novel that touches on the famous artist. For further information, visit evasiroka.com.