Art Essay: Alice Barber Stephens: Emerging Ways of Living & Working

By Rena Tobey ©

ART TIMES Winter 2014

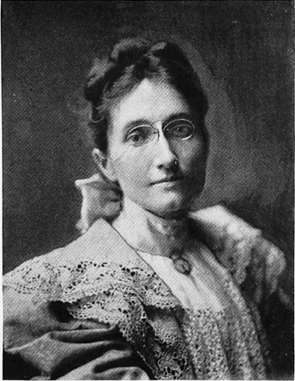

Alice Barber Stephens |

After the Civil War, pressure escalated for American women’s lives to change. Women artists, particularly illustrators, found an interested audience for unpacking the complexities of the issues involved, when depicted in clear and cogent ways. One particularly successful example came from Alice Barber Stephens (1858-1932) with her illustration called Woman in Business from 1897. In this one painting, she captured the transitions, ambiguities, and forces grappling both for change and sameness.

When her family moved to Philadelphia from their New Jersey farm, Barber Stephens began formal art training at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, now the Moore College of Art. Students learned pragmatic, income-generating forms of art that were acceptable for women, such as industrial design, illustration, and printmaking, and by the age of 15, Barber Stephens was making money from her engravings. Empowered, but perhaps not completely satisfied, in 1876, she was one of the first women to enroll in the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA). She then joined the women artists petitioning for more life drawing classes.

Life drawing was essential for any artist’s success. Being able to portray the figure in an anatomically correct way meant artists could then make paintings considered significant by their colleagues and collectors. History paintings with religious, literary, and historical subjects relied on the beautiful depiction of the human form. Traditionally, women were excluded from life drawing classes, considered inappropriate for a woman’s supposedly delicate sensibilities. Consequently, women were unable to compete for Academic recognition and commissions.

Alice Barber Stephens, The Women's Life Class, (illustration for William C. Brownell; 'The Art Schools of Philadelphia;' Scribner's Monthly 18; Sept. 1879), ca. 1879, Oil on cardboard, 12 x 14 in. Credit: Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia. Gift of the artist |

The PAFA women advocating for life drawing classes were successful, with the compromise solution of gender-separated classes. Barber Stephens got her first image credit for Women’s Life Class, in “Scribner’s Magazine” in ca.1879. In it, she provides a glimpse of what the class was like. Although still revolutionary, the only nudes were women models, while male models were modestly draped. The informality and collegiality of the students, along with their professional intent and focus, match similar depictions by men artists historically.

Barber Stephens pursued her career with that kind of professional ethos. She worked from models for her illustrations, hiring them to pose from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. every weekday, with an hour for lunch. She committed herself to not only building her own career, but also contributing to developing paths for women artists. Along with Emily Sartain, in 1897, she established the Plastic Club, which provided women the opportunity to learn through lectures and exhibit, sorely lacking elsewhere. Frustrated by the limited work in engraving, she turned to illustration, a practical and fruitful new avenue for both men and women artists.

After the Civil War, the literate middle class consumed a new entertainment economy that included newspapers and magazines. With advancement in technology, these publications featured stories that could be illustrated. Periodicals proliferated to over 2000 publications published weekly or monthly, each demanding professional illustrations. Becoming an illustrator was a smart business choice for artists, creating recognition and a stable, income-generating career path. Many of America’s most famous artists, such as Winslow Homer, began and sustained their careers as illustrators.

Although commercial art did not have the cachet of easel art, created as luxury goods for the high-end patron, illustration increasingly became an acceptable career choice for women. As mores about art education continued to loosen, beliefs started to change, too. Because exposure to art was long considered morally uplifting and women were thought to have innate sensitivity to art, the idea of a career that could be conducted at home actually supported traditional gender roles rather than challenged them. Separate Spheres ideology, prevalent in the 19th century, called for men to venture into the Public Sphere of work and politics, while women managed the domestic Private Sphere of the home and moral development of families.

But societal changes during and after the Civil War challenged those traditional notions, particularly as the United States continued to shift away from its agrarian roots toward an affluent, urban, industrial society. The Progressive Movement of the latter half of the 19th century emerged out of the resulting social anxiety. The Woman’s Sphere was becoming both a point of oppression and a point of departure for women who wanted to influence their worlds. The early feminists began to leave the home to participate in clubs as moral and cultural guardians, focused on cleaning up cities and helping African Americans, impoverished women, working children, immigrants, and other previously ignored groups.

These social improvement efforts were not the only agendas taking women of leisure out of their homes. With the boom-bust, industrialized economy, women assumed new duties and responsibilities. If they were leaving the Domestic Sphere, they could bring their skills as stabilizers for the chaotic Public Sphere with them. Quite simply, they could assume the role of consumer. Traditionally the male purview, women could now spend with a tinge of moral certitude, as contributors and a calming influence on temperamental economic markets. To further encourage consumerism, “Godey’s Lady’s Book” even started a shopping service for readers, selling their advertisers’ products.

Barber Stephens was one artist who took advantage of the explosion of illustration opportunities, including the opportunity to work from home. Like many women artists, she married a fellow art classmate, Charles Hallowell Stephens. She continued to work as an illustrator, even after having their son. Her subjects ranged widely from the Romantic to Quaker meetinghouses to almshouse residents, demonstrating sensitivity to social issues.

Alice Barber Stephens, “The Woman in Business.” Cover of Ladies’ Home Journal (September 1897). Courtesy of Rutgers University. |

Woman in Business was part of a six-part “American Woman” painting series produced for “Ladies’ Home Journal” in 1897, when Barber Stephens was at the peak of her career. The series illuminated the expanded Woman’s Sphere by focusing not only on middle-class Philadelphia women at home—as a mother, at church, and at leisure—but also in the economic world. Woman in Business is set at John Wanamaker’s department store, elegant with its stained glass window, like a cathedral of consumption. The store is crowded with customers and clerks.

The sumptuous tones of brown and black soften what is a stark depiction of class separation. The counter divides the clerks, squeezed by circumstance against shelves filled with goods, from the customers in a wide-open space. The counter is spot lit by the bright white bolt of fabric under consideration by a wealthy customer, accompanied by her well-groomed, fancy dog, reinforcing this woman’s leisure class. Viewers can also read the class difference in the attire of the figures arranged along the long diagonal of the shop’s counter. Seated at the center of the diagonal, the woman consumer wears the latest fashion of mutton chop sleeves and a high-collared, crisp-white shirtwaist. With gloved hands, she fingers the goods presented her.

On either end of the diagonal is a girl. One, pushed all the way to the extreme foreground of the picture plane, is the antithesis of the ornamental dog and well-heeled consumer. The hollow-eyed child, perhaps an immigrant, is already at work as a shop assistant. Her workaday clothes contrast with the pampered young lady dressed in her pinafore and bonnet, shadowed in the rear, at the far end of the diagonal. Stephens’ emphasis on the poor child forces the viewer to consider the economic system that creates such disparity, while the affluent child almost blends into the background, minimizing her importance.

The store is crowded and the faces blurred, except for the highlighted features of the deferential shop clerk. The title is Woman in Business, but which central figure does it refer to—the woman with the economic upper hand or the highlighted clerk? Both were women in business in their day. The woman forced to work for a living as a salesclerk had to learn to maneuver in the Public Sphere of the business world. Only white, privileged women were spared the necessity to work. In the hierarchy of labor choices for women in the late 19th century, this salesclerk was relatively well off. The affluent woman is also a woman in business, enacting her moral duty to consume the products manufactured or imported, to participate in the economic engine that fueled America’s prosperity.

Barber Stephens gives the viewer a knowing portrayal of the ways in which women had to navigate the divided spheres of American culture. By the latter part of the 19th century, most women were engaged in some way with the Public Sphere, with their role class-determined. Barber Stephens, too, was complicit in the woman in business moniker. Over her 50-year career, she made illustrations for pay, as a commercial artist, engaged in the business of boosting sales, whether of magazines or products her illustrations advertised. In this subtle way, the Separate Sphere ideology was being tampered with—acting in an acceptable home-based occupation of commercial artist, yet using Public Sphere strategies of marketing and salesmanship. With her most popular image Woman in Business, Barber Stephens pushed her contemporaries to see the broader ways that women were becoming more visible and central in the social and political world of America’s Gilded Age.

This essay is the third from the "Finding Her Way" series, exploring the challenges American women artists faced from about 1850 to 1950.

Previous essays:

Elizabeth Okie Paxton Summer 2014

Lilly Martin Spencer Fall 2014