Art Essay: Isabel Bishop at Bard

By Raymond J. Steiner

ART TIMES August 1989

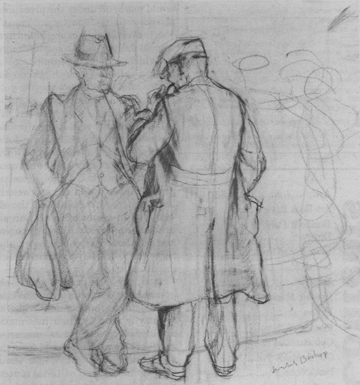

“Men Union Square” Isabel Bishop (c. 1928) Pencil |

THERE IS NOTHING more revealing about an artist than the sketchbook, often serving as the key to the artist's vision and aesthetic aims. It has been my experience that few painters voluntarily share their drawings and sketches even in the privacy of their studios - tucking them away as would some introverted diarist — let alone exhibit them or offer them for sale, so close are they to the innermost workings of their minds and souls. Understandable, then, that a show such as "Chasing the Shadows of the Times: The Drawings of Isabel Bishop and Her Colleagues" at the Edith C. Blum Art Institute, Bard College* has elicited such excitement. Fortunately there exist such innovative directors as Linda Weintraub who has curated the show and such institutions as the college art gallery since exhibits devoted solely to drawings are rarely seen, especially in commercial galleries where, I am repeatedly told, they rarely pay back the investment necessary to mount them.

This exhibit of approximately 125 of Bishop's drawings — the core of the show — includes drawings by other artists which, though consonant with the theme of drawing, tend to break up the continuity of her work, serving more as a distraction (abruptly interrupting the flow by being plumped — arbitrarily, it seems — in the middle of the Bishop exhibit) than as an aid in understanding her development. Fortunately, these (and, less fortunately, several paintings including a recently discovered mural, "Kenneth Hayes Miller Mural Class, Art Students League, 1927" uncovered by the League and shown here for the first time) will not be included in the exhibit as it travels on its tour.

Concentrating as it does on Bishop's drawings, the show is not only a valuable contribution to our better understanding of her larger ouevre but serves as a critical corrective to the general lack of focus on the role that draftsmanship plays for many artists. For Bishop (as it was for most serious artists), drawing was of prime importance in her development, often referring to its practice as "nourishment" in both her speech and writing. So important was it, in fact, that its occupation of her time — along with etching and printing — seriously curtailed her painting time, resulting in an output of canvases that seldom exceeded 4 or 5 each year.

The significant role that Bishop's drawings play in her development as a painter is given critical and astute attention in Weintraub's essay, "Isabel Bishop — First Impressions." This excellent analysis of Bishop as draftsman is published along with several of Bishop's drawings in a small catalog accompanying the Exhibit. The essay is reprinted in a more lavish monograph, Isabel Bishop, by Helen Yglesias and published by Rizzoli International Publications (180pp.; 11 x 11 1/2; approx. 250 Illus., 70+ in Color; Introduction by John Russell; $45.00 Hardcover) which is also available at the Exhibit. Weintraub's essay, however, is inexplicably tucked in as an Afterword to the Rizzoli book, a rather unfortunate decision since Weintraub has not only offered important insights into Bishop's ouevre but has written one of the best critical analyses of the importance of drawing we've seen in quite some time while Yglesias (a novelist) merely offers biographical data. So enlightening is Weintraub's essay that, if one can so arrange it, I would highly recommend its reading before viewing the exhibit.

Current efforts to enlist Bishop on the side of feminist issues notwithstanding, it is still of far greater importance to see and appreciate her place in art history and the role that drawing took in that evolution. If she has done numerous drawings (and paintings) of women, they were done less because she was sympathetic to the plight of the female workers she found in Union Square than that they served her aim — and her aim was distinctly aesthetic rather than political. Her own comment that there were simply "more women than men available in the Square" accounts for the fact that there were fewer men in her works — though they were by no means underrepresented. Specifically, Bishop's aims were to transform the academic training that she received under Kenneth Hayes Miller — a training that clearly emphasized Renaissance principles of composition — into a purely American and modern (for her) idiom.

The path that she chose to accomplish her aims — and which she arrived at through her drawing — was to de-emphasize the grand composition which presented a static world and to concentrate on the transitory human gesture. As Weintraub aptly puts it in her essay, Bishop's "challenge was to present the figure as a verb — active, transitive, evolving." In Bishop's words, "I think it's something perhaps to be justified — making one's motif out of gestures. If you think of work that has put so much value on that aspect, I suppose you'd think of genre painting. In this case, you'd think of the little Dutchmen who did this, but, of course, in a superlative way, so that you might say there was no reason to try this again, ever. But on the other hand, our life is entirely different, and it gives one a feeling of exploration to try to find some gestures that are characteristic of our life."

To find that particular "American gesture," Bishop discovered her best possible inspiration to be the transient population of Union Square. If a good many of the characteristic gestures she has managed to capture are made by women, there are not a few made by the "bums" that shared the Square with them but, what is more important is that she found her justification in that all were American. Ultimately, Isabel Bishop was to arrive at that one gesture which transcended all labels of gender, nationality or race: that of walking — the quintessential gesture of homo erectus, that lurching, awkward, almost-on-the-verge-of-falling gait peculiar to the human biped, developed over the eons in its attempts to move from place to place.

Weintraub identifies four phases in the development of Bishop's works through her drawings: "the controlled renderings of her student illustrations in the 1920s, the nervous line drawings of the 1930s, the full-tone ink gouaches of the 1940s and 1950s, and the atmospheric walking figures of the 1960s and 1970s." Although Bishop discussed this last phase of her development as being one in which she was striving to capture "movement," we can see here that the larger development of her search for that gesture which would distinguish her work from that of past genre painters had carried her — perhaps unconsciously — into the universal human gesture of walking. She once said in an interview with Patricia Depew, "I have come to think that walking is absolutely beautiful, and I could not tell you why." She had simply stumbled onto a statement of such generality that it brought her art to a point most artists only dream of — that of universal recognition and appeal. That her concentration was not, ultimately, on male or female — or even on "Americans" as she believed — but on the human figure, was her supreme accomplishment.

In addition to the two catalogs mentioned, there are two video tapes available to the public. The first is an interview between Linda Weintraub and Dorothy Dehner, a contemporary of Isabel Bishop. The second, "Isabel Bishop: Portrait of An Artist" by Patricia Depew is an in-depth interview with the artist in her studio overlooking Union Square. Distributed by Home Vision and available through their offices, the tape runs 30 minutes and brings to life the scenes of many of her works. For a look into the personality and work of Isabel Bishop, those who appreciate this artist's work can order the tape by calling (800) 262-8600. Isabel Bishop is represented by the Midtown Gallery, 11 East 57th St., NYC, a long-standing association which began in the early 1930s.

*"Isabel Bishop," Edith C. Blum Institute, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY (Jul 2-Aug 24); Bronx Museum of the Arts, Bronx, NY (Sep 21-Jan 21, 1990); Brevard Art Center and Museum, Melbourne, FL (Mar 1-Apr 26, 1990); Arkansas Art Center, Little Rock, AR (May 10-Jul 5, 1990); The National Museum for Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C. (Jul 24-Sep 9, 1990); Fine Arts Center at Cheekwood, Nashville, TN (Sep 22-Nov 18, 1990).