Art Review: Matisse and American Art at the Montclair Art Museum

By Christina Lilian Turczyn

arttimesjournal February 24, 2017

“In her statement accompanying the portfolio, Pickett refers to having discovered Matisse and that she ‘fell in love with his color and dreamt of living inside his rooms.’” —Exhibition Panel, Inspired by Matisse, Montclair Art Museum (2017)

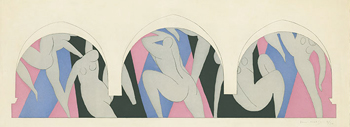

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) La Danse (The Dance), 1935-36 Color aquatint in black, gray, rose, and blue Platemark, stone or block: The Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation Collection ©2016 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York |

As I walk through a gallery featuring the probing, multi-layered work of Janet Taylor Pickett, an insight on one of the accompanying panels captures my attention: “The gesture of outstretched arms addresses the paradox of becoming strong by profoundly opening up.” It is the process of opening up, of gradually reaching beyond frames, as well as re-defining twentieth-century concepts of vision and perspective, that characterizes the work of the many contributors to Matisse and American Art, a comprehensive, groundbreaking show at the Montclair Art Museum that, according to Chief Curator Dr. Gail Stavitsky, took five years to prepare with co-curator Dr. John Cauman. Matisse and American Art includes 19 works by Henri Matisse, as well as 44 works by American artists, in addition to archival material. Several of the artists featured in the show are Sophie Matisse, Romare Bearden, Helen Frankenthaler, Faith Ringgold, Andy Warhol, Max Weber, Roy Lichtenstein, and Robert Motherwell. Gail Stavitsky stresses that artists whose work was selected for this exhibit were not by any means imitative, rather, “inspired by Matisse’s approach.” The scope of the work presented, as well as the thematic organization, make this event different from those that came before it. The exhibit traces Matisse’s influence on American art from 1907 to the present and runs from February 5-June 18, 2017. Matisse referred to his Cut-Outs (1947), created in the last decade of his life, as a culmination of his life’s work. Perhaps those moving, syncopated pieces offer a metaphor for the art featured here—an open window in which interior and exterior realities are no longer separate, but side-by-side, as are the shapes in Matisse’s portfolio of prints, Jazz (1947).

Windows

Judy Pfaff (b. 1946) Six of One – Meloné, 1987 Color woodcut Collection of Judy Pfaff, Courtesy of the artist. |

At the time of this writing, doors shut at airports around the country. Some travelers cannot get in, while others cannot leave. I ask myself if silence is a window. Do individuals express who they are, most deeply, in silence, without words and their inevitable histories distorting others’ understanding? Today, this is exactly where I want to be. Not because art is an escape, but because art removes the illusory glass, apparently invisible. Parents need only to think about a child trying to reach for a bird beyond the sill, so as to understand the nature of windows. Art, however, lets in the air --removes barriers. Matisse’s luminous, direct colors, often applied in thin layers, “breathe,” as Clement Greenberg observed in The Influence of Matisse. Later, the artist’s Cut-Outs remove the metaphorical glass, distance between self and other. And so, the works, created by “drawing with scissors on sheets of paper colored in advance, linking line with color, contour, and surface,” offer brilliant hues without mediation, as though Matisse’s scissors would cut sky. A photo featured by the Museum of Modern Art depicts Matisse in 1952, at the Hotel Regina, contemplating and creating, amid fragments of his work. The artist, using a wheelchair, is in the work, surrounded by his landscape, as it were. In the course of a lecture, Gail Stavitsky mentions that Matisse referred to the process of creating the Cut-Outs as “sculpting with color.” In the abovementioned article, Clement Greenberg calls attention to the gradual “opening out” of Matisse’s work beyond the canvas. The Cut-Outs resemble stained glass windows without glass, yet they are so much more. Vibrant colors are contiguous, wavering at places where they meet, expressing a physics of the twentieth century that suggests constant movement, music. Gail Stavitsky notes that “For Matisse, all the colors sing together…like a musical chord.” Here, time dances. Figures in The Dance (1935-36), seem, also, to bend time. Images need no frames.

I need only to look at Matisse’s Interior at Nice (Room at the Beau Rivage, 1917-1918) to see the evolution of the artist’s vision, the way in which windows gradually lose their corners. In this oil painting, the window is open; the sea rocks quietly beyond its frame. A breeze, which blows inward with a gentle force, sculpts curtains. Memories, lives—return after war. Coat hangers wait for coats. The season is warm, expectant. This painting, with an ornate, heavy frame, allows the outside to come in. Through the curators’ interpretive lens, the windows in this room suggest a tension between the artist’s interior and exterior realities. I would add that the flattened space of the later Cut-Outs collapses that distinction, becomes space itself.

Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997) Bellagio Hotel Mural: Still Life with Reclining Nude (Study), 1997 Cut-and-pasted, painted and printed paper on board The Roy Lichtenstein Foundation Collection © Estate of Roy Lichtenstein |

That movement from depth to concrete poetry is taken up by artists who engage with Matisse’s window theme. In her essay, The Role of the Window in the Art of Matisse, Carla Gottlieb alludes to that development. I would take the concept of the window one step further to emphasize artistic freedom.Is Sophie Matisse’s collage, Weather or Not (2014), created in response to the Cut-Outs, a conversation with her great-grandfather’s oeuvre? (The artist reminds viewers that she “will always paint, regardless of who came before…”). A window in her work, The Conversation (2001), appears to be cut out of infinite, sapphire space. A tree grows beyond the dark latticework. Henri Matisse and Amélie, his spouse, are intentionally left out of the work, which was part of Sophie Matisse’s Be Back in 5 Minutes premiere at Francis Naumann Fine Art. Milton Avery’s March on the Balcony (1952) depicts a figure in a liminal space, while Roy Lichtenstein’s Bellagio Hotel Mural, Still Life with Reclining Nude (Study, 1997), bridges interior and exterior views through leaves and parallel stripes. At the same time, Richard Diebenkorn’s Blue Surround (1982) looks onto infinity. Some windows lie beneath the level of consciousness. Some open up the body’s rooms. These are windows that listen.

Color

Mark Rothko (1903-1970) No. 44 (Two Darks in Red), 1955 Oil on canvas © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York |

Ellsworth Kelly is quoted as observing that in the Cut-Outs, “Matisse’s whole lifework was leading to the freeing of color and form from a ground.” Matisse’s act of making color independent of form echoes the twentieth-century pursuit of freeing chronology from linearity. (I have often imagined sheets of time carried by wind). Matisse’s Icarus is forever suspended in a moment of flight, while The Swimmer does not belong to any particular era. Henry Lyman Saÿen’s magnificent Still Life (ca. 1912), lends primary colors a shining quality, as after a rain.

When considering the influence of Matisse’s palette, it would be impossible to select any one work from among the illuminating, diverse works featured here. Mark Rothko, profoundly moved upon seeing Matisse’s painting, The Red Studio, observed: “You become that color, you become saturated with it, as if it were music.” Rothko’s No. 44 (Two Darks in Red, 1955) is a window that allows one to experience his emotions. The dense, rich colors flow without a vocabulary of form. One has the sense, as well, that the painting is the artist. Unmediated, powerful color does not lie, but confronts. In my mind, Helen Frankenthaler’s Untitled (2002) conjures a similar, profound effect. Her colors are so alive that the viewer is not sure she has ever seen them, pulsing this way. Is light a particle or a wave?

There is a bit of synesthesia in these artists’ perceptions of their environments. That is, perhaps, the dream of the twentieth century. To hear painting. To see music. To break down the walls of time. To create simultaneity. To dream the body. To externalize the mind.

Movement

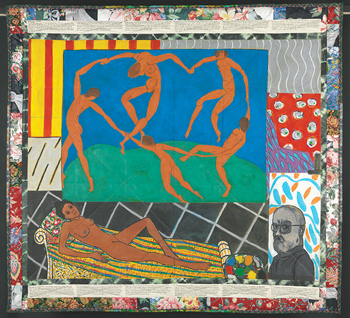

Faith Ringgold (b. 1930) Matisse's Model, 1991 From the Series: The French Collection Part I; #5 Acrylic on canvas, printed and tie-dyed fabric, ink © 2016 Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York |

The weather beyond an open window is constantly changing. No one would wish to control what enters a river, or the Web. Like a river, this exhibit moves toward the past and present; undeniably, the work is powerful, expressive—not elusive. At the end of my visit, I look back at the galleries and notice that motion defines almost all of the work that I see. Nothing in this gallery stands still. Einstein speaks of relativity. Matisse slices time. Artists both affirm and question Western traditions, for Matisse’s rich legacy is a complex gift. Faith Ringgold’s Matisse’s Model (1991) looks out towards viewers, not Matisse. Words inscribed at the borders of Ringgold’s work ask why wars begin. Romare Bearden’s female figure of The Dream (1970) is extremely compelling. The title of the artist’s work at once affirms context and removes the figure from the gaze. Her vision is her own.

As part of the exhibit titled The Matisse Series, Janet Taylor Pickett’s collage, Entering Desire and Creation (2015) foregrounds the image of a door. Her Matisse Blue Dress (2013) places her version of Matisse’s figure in a “power stance.” Many of Taylor Pickett’s paintings engage autobiography. The surface image leads the eye, as through layers of historical significance, into her life and heritage. Birds leave the body, like words.

Often, I have thought about the windows and doors in my own life. Some doors beckoned, and led to nothing. Some doors lied, and did not open. Certain doors freed. Certain doors closed. Doors are a great deal like myths. Symbolic, rectangular doors approximate the American Dream. Is the voice of the palette a powerful form of expression, without the temporality of perspective? Here, time is expressed in circles, not lines. This exhibit leans towards the future. Whose voices remain to be discovered? Whose books remain to be read?

Matisse and American Art is a freeing window. When I view Rothko’s abstract expressionist painting and discover that he created this piece in response to a profound encounter with color, I think of a window for sound, sound which does not require translation, sound that directly seeks the eyes. I have the same experience when I see Lee Krasner’s Free Space of sensuous green (1975) or Sophie Matisse’s electric field of blue. All of the artists in this show look beyond the glass. Viewing the work of the artists in this exhibit, I am reminded of James Baldwin’s Sonny’s Blues. I return again and again to the ending of the narrative, in which the protagonist leaves the shore of safety, wades into the deep water of his own artistic knowing, and there, without hesitation, finds everyone he ever knew.

A green branch--

It might be truth

settling on one’s shoulder.

It might be the self,

returned to the self,

after a long absence.