Art

Review:

Keith Haring: The Political Line at the de Young Museum

(All photographs by Norman Kolpas©)

By Norman Kolpas

ART TIMES February 2015 online

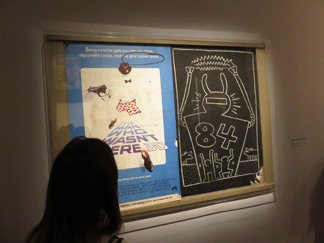

Untitled (Subway Drawing) 1984 chalk on paper |

A major retrospective of any artist’s career usually offers the public a rare opportunity to appreciate the totality of that creative soul’s output. If nothing else, it enables art lovers the satisfaction of knowing that they’ve literally seen it all—and, if it matters to them, the bragging rights of being able to tell others they have.

By that standard alone, Keith Haring: The Political Line—which originated at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 2013, has been on view at San Francisco’s de Young Museum since last Fall (closing this February 16), and moves on to the Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung in Munich from May 1 to August 30—is an exceptional exhibition, spanning the too brief career of the seminal 1980s street artist with more than 130 paintings, sculptures and works on paper, gathered from the Keith Haring Foundation and from many private collectors. The long queues to enter on time-stamped tickets, and the crowds thronging the de Young’s spacious basement-level special-exhibition galleries, certainly attest to the comprehensive show’s mass appeal, as well as to the enduring public affection for a man who rose to phenomenal worldwide prominence and popularity as a cartoonish street artist—progenitor of current popular figures including Shepard Fairey and Banksy—before succumbing to AIDS-related complications in February 1990 at the age of just 31 years.

To be honest, I must admit that I’d planned to attend this Haring show as a fun Saturday afternoon activity on an early-January visit to my son Jake, who had recently moved with his girlfriend Emily to San Francisco. Both Jake and I are big fans of pop culture, and this seemed like a bit of a lark we’d enjoy together. But neither of us were prepared for the impact such a smartly curated and displayed assemblage of Haring’s works would have on us, causing us both to rethink our impressions of the artist.

Untitled (Apartheid) 1984 acrylic on canvas |

Which brings me to a benefit bestowed by some much more rare retrospectives. Beyond mere comprehensive exposure to a lifetime of output, these help viewers to understand the creative spirit in a new light, providing fresh perspectives and insights, through both the works selected and the ways in which those pieces are juxtaposed.

By such a criterion, The Political Line puts Keith Haring much more squarely within the context of his tragically brief time. As that title suggests, it examines the way his deeply held beliefs on key social issues—including apartheid, police brutality, environmental catastrophes, the growing undue influence of mass media, the commercialization of art, gay rights, and the AIDS crisis—often compelled him to create. In room after room, the exhibition’s guest curator Dieter Buchhart and co-curator Julian Cox of the de Young deftly interweave chronological and thematic approaches, paralleling the developing consciousness of Haring with his burgeoning artistic skills.

Trained in both commercial art illustration and fine art, Pennsylvania-born-and-raised Haring found graffiti art a perfect populist style and medium when he began making public art while still a student at New York City’s School of Visual Arts, where he enrolled in 1978. The subway platforms of the Metropolitan Transit Authority promised a perfect venue, its tiled walls promising an audience of literally millions of passersby each day.

Silence=Death, 1988, acrylic on canvas |

To grab passengers’ fleeting attention, Haring developed his now-iconic, characters: Everymen defined by a simple chalky white or poster paint black outline, like cartoonish spins on the stick figures seen around the world in signs for crosswalks, public toilets, and other venues. Childlike and yet endlessly expressive thanks to the artist’s talent for capturing emotion in the tilt of a head or the bend of an arm or leg, they possessed the ability to convey messages almost at a glance and amid milling crowds. Indeed, the presence at the de Young show of so many people, which I often find a distraction or nuisance at popular exhibitions, miraculously seemed only to enhance the experience of Haring’s works, almost as if they were being seen under the original conditions in which they were created.

By the mid-1980s, to his own surprise, Haring had shot to international prominence. Galleries gave him shows. Cities worldwide invited him to paint public murals that expanded his palette far beyond the monochrome to vibrant colors that evoked the Disney cartoons he’d long loved as well as the Pop art of fellow New Yorker via Pennsylvania Andy Warhol, who became a friend and mentor.

Yet, while enjoying his rapid rise, Haring never lost sight of his populist roots. In 1986, he opened his Pop Shop in New York’s SoHo, a retail outlet where anyone could buy authorized posters of his work, t-shirts, buttons, and other merchandise that made his Everyman images available to every man and woman.

Untitled (Self-Portrait), Feb 2, 1985, acrylic on canvas |

As the show dramatizes, success made Keith Haring only more aware of his art’s potential to influence social change. He boldly outlined scenes of social strife, portraying innocent souls being attacked by dogs or beaten or impaled by authority figures. One significant large-scale piece on prominent display is his 1984 acrylic-on-canvas Untitled (Apartheid), depicting a large black man holding a red-glowing cross while kicking out against the puny white figure ineffectually attempting to control him with a leash and collar around his neck. Widely reproduced and sold on posters, badges, and shirts, the image built awareness of and contributed significant funds toward the movement to dismantle apartheid and free Nelson Mandela. Viewed not in those smaller mass forms but in the original, the 1173/8 by 1433/4-inch work has as commanding an emotional effect today, its dramatic yet simple composition conveying meaning with every line, as it did more than 30 years ago.

Again and again, the Haring retrospective proves surprisingly moving. Sometimes the emotion evoked is laughter, as when the artist superimposed Warhol’s bespectacled, shaggy-haired physiognomy atop multiple images of a beloved Disney character against a dollar-green field with floating black-and-yellow dollar signs in a 1985 acrylic-and-oil work he entitled Andy Mouse. Clearly, Haring’s respect for his art world friend did not prevent him from such playful commentary on how both he and Warhol profited from their Pop popularity.

Andy Mouse, 1985, acrylic and oil on canvas |

The artist’s response to the AIDS crisis that soon would claim his own life increasingly found expression in his creations as well. Most impactful is Silence=Death, a title Haring borrowed from the motto of ACT UP, the Aids Coalition to Unleash Power. The giant pink triangle, itself a symbol of gay pride, is covered in masses of Haring’s familiar figures, here drawn in shiny silver paint, each in a pose of covering its eyes, ears, or mouth: see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.

Movingly, an adjacent wall, just before visitors leave Keith Haring: The Political Line, displays a large-scale self-portrait Haring created in 1985, when he was not quite 27, three years before he learned he was HIV-positive. Looking surprisingly lifelike in the artist’s signature cartoonish lines, his ruddy complexion a rough rendering of the kind of blown-up Ben-Day dots Roy Lichtenstein borrowed from comic books, he looks filled with hope and ideals. The realization that he lost his life almost exactly five years after he painted it brings this thoughtful retrospective to a powerful, poignant conclusion.

Keith Haring: The Political Line; (thru Feb 16): de Young Museum, Golden Gate Park, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive, San Francisco, CA 94118, 415-750-3600; (May 1–Aug 30): Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung, Theatinerstraße 8, 80333 Munich, Germany, +49 89 224412 .

Norman Kolpas is a Los Angeles-based writer on art, architecture, travel, dining, and other lifestyle topics. HIs work has appeared in publications including Southwest Art, Mountain Living, Sunset, The Times of London, and the Los Angeles Times. Norman also teaches nonfiction writing in The Writers' Program at UCLA Extension.