Art Review: Freedom in Imagery

found in Los Angeles this Winter

By Jean Bundy

arttimesjournal March 17, 2017

In view of Washington’s present administration, questions concerning the wide definition of freedom are being challenged. In reality, many people are not free to come/go, speak or live a life without strife. Does art give us answers or in the least, does it ask needed questions and maybe provide some solace? While visiting son Oliver in Los Angeles, I viewed several exhibitions, which contained art that would not have been made if there hadn’t been some kind of political conflict brewing. Resolution is often fleeting, yet it is the process of seeking freedom that should be unpacked.

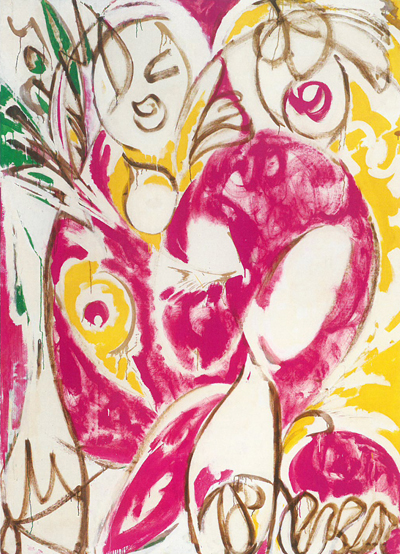

“Willem de Kooning” by Elaine de Kooning ( scanned by the Author from the exhibition catalog) |

Los Angeles County Art Museum’s show, Moholy-Nagy: Future Present (thru June 18, 2017) presents his wide variety of media experimentations executed under both restrictive and capitalist conditions. Like many insightful Eastern Europeans who anticipated further oppression from authoritative regimes, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) moved from Hungary to Germany, Amsterdam, then to London and eventually the United States seeking artistic freedom and a new social order which he felt could only be explained through abstraction.

In 1923, architect Walter Gropius invited Moholy-Nagy to be the art administrator/faculty at the Bauhaus. As a teacher he worked in all media: metals, photography, printmaking, painting and sculpture. Moholy-Nagy left the Bauhaus in 1928 to open his own Berlin design studio, but the Bauhaus, closed by the Nazis in 1933, is forever associated with this artist who contributed to a curriculum combining industrial design, fine art and academics into an aesthetic program.

Moholy-Nagy was influenced by Dada, Surrealism and Constructivism. Consequently his art contains print, fantasy and the predominant red/ black hues associated with socialist art often made by a collective. In the early twentieth century, the importance of surface color to a work was debated, as it is after all illusory on any surface. At the same time, light, a component of color was isolated for its scientific and objective materiality while being associated with the new technological era.

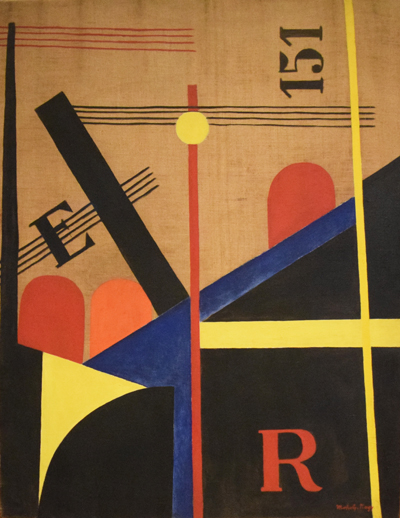

“The Big Railroad Picture”, 1920, by Moholy-Nagy (photo: Dave Bundy at LACMA in Los Angeles) |

In the late thirties Moholy-Nagy was invited to become director of the New Bauhaus (today, the Institute of Design, IIT) in Chicago by Walter Paepcke, chairman of the Container Corporation of America. Of interest: if you take in a concert at Aspen’s Paepcke Auditorium (in 1982 I attended a John Denver concert) or attend a conference at the Aspen Institute, Paepcke’s name and endowments abound. And Moholy-Nagy is buried at Graceland Cemetery, Chicago—I have stood by his grave. Freedom can be found in the creativity of Maholy-Nagy’s work as well as in his luck to have escaped the Nazis.

Moholy-Nagy’s The Big Railroad Picture, 1920, is an example of layering socialist art practices with Modernism adopted when living in the West as seen here in his socialist palette of reds/blacks that expanded with yellows and blues. Although this is a painted work, ideas taken from newsprint collage, popular because it was cheap, are felt in the overlapping shapes and use of lettering. Trains are known by their numbers and parallel lines that conjure musical notation suggest railroad tracks. The yellow circle atop the thick red line against the wide diagonal black line is reminiscent of manual switching systems, necessary for flawless operations before computerization.

The railroad is synonymous with capitalist industry and dictatorial regimes, as steam engines carried commerce but also removed dissidents. Like many artists who fled Eastern Europe, Moholy-Nagy’s art continued to contain socialist constructs, morphing into capitalist imagery, representative of his newly acquired freedom to create at will.

The Louis XV Hand ( photo: Dave Bundy at the Getty, LA) |

Over at the Getty Museum was the show Bouchardon: Royal Artist of the Enlightenment (thru April 2, 2017). Edme Bouchardon (1698-1762) was a French sculptor. Finesse found in his ability to render classical themes on paper was exquisite. While Bouchardon’s sculptures document an era of stately power, from the perspective of any aficionado of Bernini’s ability to breathe life into stone, he’s a bit clunky. Bouchardon’s Right Hand from the Equestrian Statue of Louis XV, 1758, is all that remains of the statute of Louis XV and his horse, which were melted down and recycled for the French Revolution in 1792. The hand, once a trope of tyrannical times, continues to be an appendage that represents the ultimate gesture of power which can hold a sword or a pen, thus determining someone’s fate: freedom, captivity or even death.

Breaking News: Turning the Lens on Mass Media (thru April 30, 2017) was a small Getty exhibition—sadly no catalog. This show superimposed talking-heads; theorizing television hosts are chosen as having a similar shape/size of head shot regardless of what gender, skin type or intelligence they possess. Breaking News also took sound bites from news anchors and strung them together creating a supposed new narrative, showing how similar their spiel was and how their phrases could be easily exchanged and reinterpreted. Breaking News posed that all readers-viewers can easily be duped into thinking they are free thinkers.

At the Palm Springs Art Museum, Women of Abstract Expressionism (thru May 28, 2017) presents twelve women who in the 1940s to 1950s desired, like their male counterparts, to gain acceptance as non-objective painters. New York’s Cedar Street Tavern (closed in 2006), a post-war watering hole for aesthetic discussions, barred most women painters. And it continues to be true that female artists don’t get the same round of applause or bucks in the bank as men.

“Sun Woman” by Lee Krasner (scanned by the author from exhibition catalog) |

It didn’t help that the infamous critic Clement Greenberg (1909-1994) snubbed women painters. Ab-Ex artist, Grace Hartigan (1922-2008) said, “Clem [Greenberg] got on his kick of ‘women painters.’ Same thing—too easily satisfied, ‘finish’ pictures, polish, ‘candy’….” Three years later when Hartigan had gained popularity, she told Greenberg, “In your discussion of me and my painting I think you have been flagrantly irresponsible. You must know that your remarks have been repeated to me, and that I, helplessly fuming, hear you think I am ‘not even a painter’….Whatever opinion you have of my work, you must respect my seriousness and energy. When an artist presents a show, he backs it up with his life. You are a coward because you back your words with more words.”

There is a debate as to whether West Coast female artists were treated more fairly. And another discussion ensues as to whether being married to a famous artist helped or hurt. Lee Krasner (1908-1984) and Elaine de Kooning (1918-1989) had a hard time reining in their creative spouses, to say the least. My cousin, children’s book author Joan Heilbroner (b.1922), was a secretary to a psychiatrist treating Pollock for alcoholism and has related countless times that he was rude and unmanageable.

According to Elaine de Kooning, “A painting to me is a primary verb, not a noun—an event first and only secondarily an image.” Some have suggested Krasner and Elaine de Kooning were better artists than their husbands had they been given the post-World War II ‘green light’ and subsequent laurel wreaths. Once in a while someone broke through the glass ceiling. Painter Mary Abbott (b.1921) was a Manhattan debutante with a studio in South Hampton. She had money to take lessons from Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko and managed to frequent the Cedar Tavern. Her work shows a similarity to de Kooning with whom she had a long friendship.

Elaine de Kooning’s painting Willem de Kooning, 1952, displays the frenetic brushwork that her husband employed. Here, her colors are limited to orange/black and the figure is fully clothed, whereas Willem de Kooning’s (1904-1997) women are nude, residing in a livelier uncontrolled palette. Lee Krasner’s Sun Woman 1, 1957, has some of the splatterings of husband Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) but has used pink/green primaries akin to Matisse.

Mary Abbott “Oisin's Dream” (scanned by author from exhibit catalog) |

Mary Abbott’s Oisin’s Dream, 1952, has taken the mad-dash brushstrokes of Willem de Kooning and directed them into a three-tiered landscape, albeit abstract. Her grayed out ultramarine blue in the foreground, earth tones in mid-section against a background of various tones of blurred purple, feel like Monet’s pond in a thunderstorm. Abstraction helped pave the way for ‘Women’s Lib’ even though these ladies still needed to piggy-back on male counterparts.

Four West Coast exhibitions illustrate how art portrays a variety of freedoms. Moholy-Nagy represented the positive aspects of technological advancements once away from social and economic oppression. Freedom for him became making/administrating art in Chicago. The eighteenth century Bouchardon, representational as was the custom, earned a living sculpting the powerful. Today, his remaining bronze hand has lost its regality and former narrative but takes on new meanings: power acquired by the masses while representing the absent whole of the body-politic.

Abstract Expressionism symbolized the United States as superpower after winning a world war. After all, women had kept the home fires burning in factories and naval yards; why shouldn’t they too partake of this new wave of victorious expression? Perhaps aesthetic freedom today is expressed in smart phone photos. Imagery continues to visually realize the need for change and the never-ending fight for freedom, hard to be ignored even by the bad guys today.

Future Moholy-Nagy Present; Bouchardon: Royal Artists of the Enlightenment and Women of Abstract Expressionism are on Amazon; Breaking News is at getty.edu.

Jean Bundy, AICA-USA is a writer/painter living in Anchorage.

Email: 38144@alaska.net