Art Review: American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent

By Jean Bundy

arttimesjournal May 10, 2017

The exhibition Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (thru May 14) is not only a chance to see how American artists painted, here and abroad, but their struggle to gain aesthetic independence from European methods. If you missed the show, the book with the same title has more explanations and illustrations.

Watercolor is a beguiling medium where the artist walks a tightrope between success and failure, referred to as mud. Watercolor, better when pigments are of quality and brushes thirsty, is considered inferior to oils, perhaps because it has been widely used by amateurs and women.

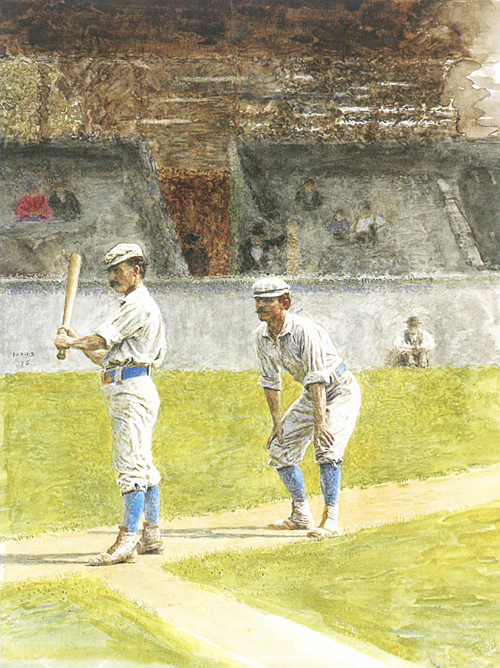

Baseball Players Practicing, 1875, by Thomas Eakins (photographed by the author from the exhibition catalogue American Watercolor in the Age off Homer and Sargent) |

In the nineteenth century, an amateur was generally a person who did not economically survive off paintings regardless of talent. Flooding nineteenth century art venues, artist-amateurs had greater means to buy supplies and time to interact with professional artists whom they often patronized. Their voluminous presence changed how we categorize artists. Today, anyone can be a professional or amateur by merely stating so. However, artists like Prince Charles choose to stay amateur, his preference for the Victorian gentlemanly way of representing the art world—Charles’ high prices go to charities. However, his cousin Sarah, daughter of Princess Margaret, calls herself a professional.

Biases over amateur/professional status and the commercialization of water media for mass marketing of post-Civil War tabloids contributed to much negativity, even though Harper’s Weekly and Scribner’s Monthly were commissioning artists like Thomas Moran (1837-1926). American painters looked to English watercolor methods, which gravitated to the transparent over opaque. Others wanted watercolor to mimic oils, which often clouded the media’s shimmer when too much white pigment was added. Yet, painters like Winslow Homer (1836-1910) or Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) had no trouble combining transparency with opacity.

British writer/painter John Ruskin’s (1819-1900) books: Modern Painters and Elements of Drawing (both still available) taught close observation to Nature, especially to color. Ruskin promoted J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) who had no problem confidently working in both oil and watercolor. American greats like John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) and Homer would facilitate both media. Sargent, Homer and Eakins added figuration to their watercolors as they boldly illustrated minorities as equals. All played with sexual ambiguities. Many compositions before the Civil War contain foreboding skies and damaged boats, an indication of the upcoming conflict.

Becoming too literal an observer of life bothered some painters. Maurice Prendergast (1858-1924) became the quintessential American watercolor Impressionist. John Lafarge (1835-1910) known for stained glass, pushed the decorative of watercolor. Childe Hassam (1859-1935) could paint rain bouncing off pavement or wind whistling through a country garden. The constant return to Romanticism’s exaggerations and a new interest in the simplicity and organization of Japanese design kept many compositions fresh. And the founding of the American Watercolor Society, 1866, further promoted the media. Politics being what they are, those rejected from AWS, banded together forming many versions of the famed “Salon des Refusés.”

Boy Fishing by Winslow Homer, 1892 (photographed by the author from the exhibition catalogue American Watercolor in the Age off Homer and Sargent) |

Americans traveling abroad introduced the brashness of American watercolor to Europe’s art scene while playing with Continental subtle tonalities, the prominence of black hues and addition of ancient ruins to landscapes. Trompe l’oeil also fetched up in watercolor as a reality game for viewers. Charles M Russell (1864-1926) and Frederic Remington (1861-1909) often worked in watercolor out West. Returning to their Eastern studios, they reverted to oils for their epic paintings or magazine illustrations. The famed teacher/illustrator Howard Pyle’s (1853-1911) mixed-media can still be found in children’s classical literature.

Like a Sousa march where the brass section dominates, American Impressionism used denser pigments and local narratives that reflected the young country’s individualism and Westward expansion. Homer, like Sargent, could paint heat or volume by leaving parts of the paper paint-free. Painter Jane Peterson (1876-1965) ventured from Illinois to Pratt Institute, finding employment with designer Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933). Peterson along with Sargent accompanied Tiffany in his private railway car, taking artists on a painting expedition to the Canadian Northwest and Alaska.

Colonial America had relied on English art supplies, which became hard to obtain during the Revolution. Shops were few and often artists sold their surplus supplies. Pharmacists called ‘colormen’ began to sell paint while other artists purchased manuals on how to grind pigments. The military needed watercolor for mapping, paint for ships, and large amounts of dyed indigo cloth from India. European Industrial Revolution saw the boom of these manufactured dyes and artist pigments, both organic and synthetic, slowly learning to make paint less fugitive. Mid-nineteenth century Britain began manufacturing watercolor in cake form. Honey and glycerin were used to make the dried pigments more workable, which allowed Winsor & Newton to put watercolor into porcelain pans and tubes. Competition between manufacturers grew along with interest in the toxicity of pigments, especially when catering to children’s paints.

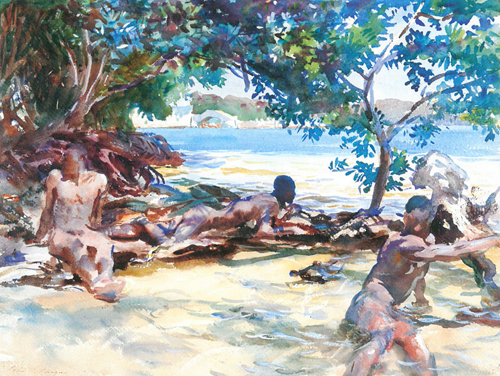

The Bathers, 1917, by John Singer Sargent (photographed by the author from the exhibition catalogue American Watercolor in the Age off Homer and Sargent) |

In this exhibition and catalogue, three watercolors struck me as truly American. They are brash yet ambiguous in narration, as figuration competes with landscape for dominance. Continuing to pay homage to traditional British Picturesque, artists still promoted the rough/ smooth of landscaping.

Baseball Players Practicing, 1875, by Eakins, expresses the concentration in batter, catcher and fans that are rendered impressionistically. The grass, wall and seating divide the composition into a traditional three-tiered landscape. Athletes dominate the scene in spite of their size in comparison to the park. Some transparency is found in the blurring of the bleachers. Is this painting about an afternoon of fun or a metaphor for the might of the Yankee North?

Boy Fishing by Homer, 1892, mixes opacity and transparency while describing the smooth/rough of a three-tiered landscape. The lonely/independent figure in the wilderness dominated post-Civil War paintings. With Jacksonian Western expansion, the boy netting one fish represents survival of the American individual over Nature. His taut pole seems to capture/control the landscape as much as the fish. Or is this just a Mark Twain-esque narrative?

The Bathers, 1917, by Sargent disrupts the traditional three-tier landscape by pushing middle ground trees into the background, creating an arboreal curtain surrounding another smaller three-tiered landscape within. But more disruptive are three male nudes lounging on hot sand. Sargent was a master at painting heat, but here he may be interpreting more than mere temperature. Gauguin painted the Polynesian female nude as the exotic ‘other’. Sargent’s virile naked males are even more risqué. Again, their solidity blends into the tree trunks overpowering the landscape and even his unique ‘play within a play’ mini landscape. But maybe this is just a beach scene? Keep on sleuthing for art.

Photos of artwork were taken by the author from the catalogue American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent.

Catalogue is available at Amazon.

Jean Bundy is a writer/painter living in Anchorage, AK

Email: 38144@alaska.net