Art Review: Ben Wilson ~ From Social Realism to Abstraction

By Christina Turczyn

arttimesjournal October 10, 2017

According to the artist, “The Builder asks a question. Man the builder is also man the destroyer. Which of his opposing forces will predominate?” --Ben Wilson

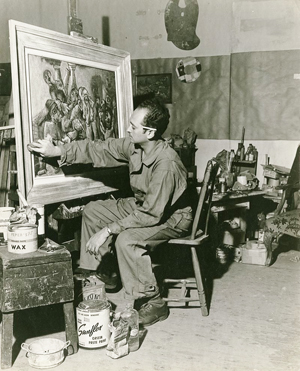

Ben Wilson at work on “The Muckrakers” in his Chelsea studio in 1944 |

Ben Wilson: From Social Realism to Abstraction, is a profoundly moving, historically expansive exhibit currently on view at the George Segal Gallery at Montclair State University, through November 4, 2017. Spanning decades of Ben Wilson’s drawings, paintings, and collages, the innovative space seems to bring this paradox to the fore. Wilson’s powerful responses to the Holocaust, to pogroms endured by his family, to the Great Depression, as well as to crises in his own personal life, can only begin a dialogue. It can take a lifetime, or many generations--to understand or to express a form of suffering that is both lived and inherited. Do individuals feel guilty because they did not live through what their parents experienced? How does anyone approach the edges of understanding, blown outward toward infinity, when bodies are broken and the sky does not speak? Where does the body end, and suffering begin? This requires the artistic courage that Ben Wilson had.

The artist was born in Philadelphia in 1913, to a family that emigrated from Ukraine. Later graduating from City College with a B.S. in social science, he also studied at the National Academy of Design. In his introduction to the exhibit titled, “The Moment of Recognition,” Jason Rosenfeld mentions Wilson’s years of teaching in the Works Progress Administration. The current collection includes early work such as a self-portrait (1935) as well as a painting titled In Plane Sight (2000) completed a year before the artist’s death, allowing visitors to see the evolution of the artist’s creations, tending in the end, as Rosenfeld observes, towards “the freedom he found in abstraction.” And this collection expresses that freedom.

In Plane Sight 2000 Oil on Masonite 53.75 X47.625 inches |

Dark Lines

“The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference.” --Elie Wiesel

As I begin my tour of the gallery, conducted by Adam Swart, Education Coordinator, I know that Ben Wilson would have enjoyed the welcoming, spacious setting. One of the first exhibition panels reminds viewers that Wilson’s Artists’ Gallery Show of 1949 included a phonograph player in the background, so that visitors could feel closer to the work, as Wilson’s voice described three pieces, one of which was The Builder (ca. 1940). Wilson wrote of death’s image reflected in the water. I see the reflection, along with humanity’s constructs cast into the quiet surface, but death’s architectural semblance does not mirror any recognizable form. Was Wilson referring to Western civilization? A recollection of cruelly structured genocide, facing the viewer, or the sky?

Victory 1945 Oil on Canvas 48X36 inches |

It is impossible not to feel what the figures in The Wasteland (1942) feel. Adam Swart called my attention to the fact that this harrowing piece was “among the most moving protests” which an Art News reviewer had seen. Fragmented bodies tumble in incalculable space, as a figure in the background, with eyes black as if fathomless, reaches towards the sky. Overhead, the clouds move with deliberate purpose. Yet the people pictured hold one another against an unyielding earth. In my mind, the initial works carry the weight of the exhibit. In their silence, those pictured in the paintings confront the viewer with an open gaze. The paintings are riveting. It is difficult to walk away.

I think about Wilson’s phonograph, and his voice describing The Builder. “Which of his opposing forces will predominate?” There are no answers here, only contrasts. Anguish and green fields. Realism and dream. How does one explain Walking Men (1958-60), who seem to blend together like sheaves? How does one explain Byzantium Revisited (ca.1984), where forms that resemble iron rods are juxtaposed with brilliant emerald and yellow? Elsewhere, in the Haiku series (1985-87) similar, dark lines approximate musical notes. In Prometheus, I imagine the tragic ambiguity of light, illuminating bone. Was the message of the phonograph akin to Ocean Vuong’s poem, Aubade with Burning City? Victory (1945) is ironic—a masterpiece, among many. The figure blowing the horn seems intentionally flat—perhaps an idea with scintillating hues. The arm of the topmost figure is serpent-like. Flames rise up from the ground. What is the cost of “victory” in any war?

Bypass 1991-92, Oil on Board 42.25 X 48.25 inches |

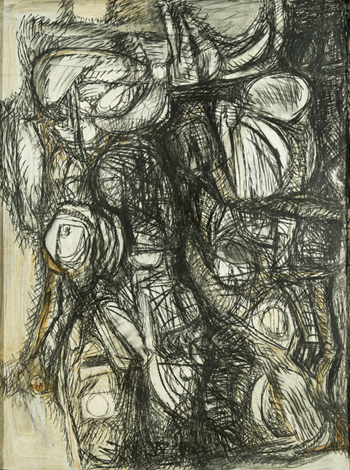

Walking into the next room, I consider the black lines that figure so prominently in the early work. Lines in Totentanz (1958-60) carve pain onto the paper, at the same time that the repetition of circles releases memory from untold layers. In later work such as Untitled (1990) and Bypass (1991-92), what might be biomorphic or human forms are still present, yet not trapped. As Wilson’s work moves away from realism to abstraction, the paintings open up from the center; lines in The Studio (1985-86) move toward open space, as do triangles in The Past Disassembled (1973). When I look at the later work, it becomes apparent that the dark lines no longer define, as they might in The Wasteland. According to Jason Rosenfeld, In Plane Sight (2000) completed one year before the artist’s death, features “black outlined forms [that]haphazardly hover on the surface,” and, I feel, from a very great distance. The arrow-like form closest to the viewer provides an entry point, not a boundary. Space bends. Questions yield to metaphysics. Something has shifted. Something has become lighter, or has been let go.

Color

“People are limiting. Shapes are not.” --Ben Wilson

Totentanz ca. 1958-60 Graphite and Gouache on Panel 48 X 36 inches |

It may be that artists who dared to look where others chose not to are the only artists who could really see. Ben Wilson’s vision and palette were constantly evolving. A new use of brilliant color arrived after his stay in Paris, where Evelyn Wilson pursued a career with Fabergé Perfumes. There is no exoticism in his work.That which some term “exotic” is part of the journey never taken—the imaginary landscape or relationship distorted by distance. Corrida (1965-66), about the bullfight, has dark branches growing upward from its base. (Wilson turned the canvas in all directions.) I think of the phonograph—what music adds, and what silence takes away. It is all very close. Eye-like forms engage the viewer. Whether figurative or abstract, grainy or surreal--the work is alive. At a certain time in his life, Wilson, viewers discover, sustained a debilitating back injury. He could not paint, but drew. Facing censorship of his work, he never stopped creating. Why, then, did his work not achieve wider recognition? Was it the result of strong stands he took in works such as Arrest of the Picket (1930s) or Victory?

Novels such as Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony evoke the possibility of nuclear destruction and healing rain. This work is about devastation. This work is about love. It is the kind of love that spares the beloved nothing, so as, in the fullest sense, to tell the truth. Whether depicting a game of Tic-Tac-Toe (1968), or a strike, Wilson is, in every moment—present. It is a viewer’s privilege to stand inside his life.

It is difficult to experience the traumas of one’s time in constant feeling and expression. Yet Wilson is endlessly and powerfully interpreting. The later work, though abstract, never abandons social justice. If he fragments and collapses space, the artist questions. Totentanz, Rosenfeld shares with readers, contains fetal figures. The past is not forgotten, but reborn, in increasingly vivid hues that lean toward the future.

Works Consulted

Rosenfeld, Jason. Ben Wilson: From Social Realism to Abstraction. Montclair State University, 2017.