Dance: Martha Graham's Legacy

By

DAWN LILLE

April,

2003

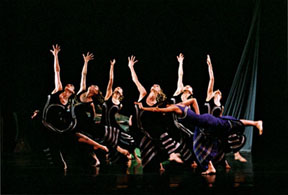

Alessanda Prosperi as 'Leader of the Chorus' and The Martha Graham Dance Company in NIGHT JOURNEY (Photo Copyright Nan Melville) |

Martha Graham — surely one of the 20th century’s outstanding and most influential creators — was a dancer and choreographer. The essence of theater, she influenced dramatists, actors and filmmakers, as well as a continuing throng of dancers and dance makers. When she died in 1991 at ninety-six her power and insight had been felt throughout the world and, to a large degree, continues to be. Thus the reemergence of the Martha Graham Dance Company for a two-week season at the Joyce Theater, after a four year hiatus filled with legal battles, was a special occasion.

The dance technique that Graham evolved, with its famous "contraction and release," and its percussive and angular movements that were quite different from the light, pulled up, flowing designs of ballet, was a form of minimalism. Her distillation of movement was an inner condensation that was, nonetheless, fraught with emotion and sensuality. Although many of the artists who attended her Sunday evening concerts in the late 20’s eventually turned to abstraction, she did not. Her great works were narrative and dramatic, told from the viewpoint of a woman – Eve, Phaedra, Joan of Arc, Emily Dickinson — and always danced by her. They frequently made use of flashbacks, a technique that many copied from her.

As a performer (she was seventy when she stopped dancing) Graham was exceptional. At one of the panels held at the Library of Performing Arts in the weeks prior to the season, Robert Cohan, once her leading male dancer, described her as an extraordinary creature in performance, with an uncanny ability to express inner thoughts and meaning through her body. Even when she was really too old to be on stage she was still capable of projecting a sense of tragedy that was superb.

My memory is of a tiny lady, hair pulled tightly back and meticulously adorned with either a velvet ribbon or lacquered chopsticks, large eyes darkly outlined and heavily coated with mascara and a red slash of a mouth. She always wore a long exotic robe to teach class, which she did once a week for each level. Her legs seemed to wind around each other when she walked. Someone demonstrated the warm-up exercises for her and eventually she had the class moving across the room. One time her instructions, given in her carefully modulated and deeply dramatic stage voice, were "Pretend there is a long stemmed rose on the piano and you are hurrying to get it. Then bring it back in all its beauty." At the time, I had no idea what she meant, but the suggestion of the potential inherent in the gestures of the body had a tremendous influence on me and so many others.The repertory in the four different programs contained examples of eight decades of creativity, from the early solos to the Greek and biblical epics. Some feel that this generation of dancers, many of whom did not have the long experience, if any, of working with the inscrutable, sometimes arrogant and often cruel and tempestuous choreographer, lack the sharp attack of her earlier dancers. But these performers have a very strong technique and an exposure to many styles and philosophies. What this new company did most movingly was to impart a warmth and humanity to many of the historical works, making them relevant and meaningful to the contemporary audience, not museum pieces. Those involved in this endeavor, particularly Christine Dakin and Therese Capucilli, co-artistic directors who danced with Graham, have this intent in mind and plan to encourage new choreographers as they train more dancers. This is a different world and different interpretations and meanings are inevitable. Graham left a strong enough legacy to support others and to allow each new group of performers to interpret and communicate her carefully crafted works in their own unique way.

Tadej Brdnik as 'Adam' and Elizabeth Auclair as 'Lilith' in Martha Graham's EMBATTLED GARDEN (Photo copyright Alexandros Giannakis |

Frontier, was first performed in 1935. A woman stands in front of a split rail fence (Isamu Noguchi’s first design for Graham), horizontal in feeling, her gaze and body indicating that the space in front of her is endless. She is the quintessential pioneer woman, strong and fearless, and Graham was to embody her several more times in different ways in her pursuit of what was American to her.

Errand Into The Maze (1947), ostensibly the story of Ariadne and the Minotaur, is really about the conquest of one’s inner demons and fears, a psychological journey Graham took repeatedly. Miki Orihara, one of several who danced the woman stepping over the rope that symbolized the maze of her doubts, was quietly and powerfully convincing.

Diversion of Angels (1948) uses music by Norman Dello Joio. Graham once said it depicted three aspects of love: mature, erotic and adolescent. Filled with examples of tenderness, joy and expectations, it is the most lyrical of her works. Fang Yi Sheu, skimming across the diagonal in her erotic red dress, was breathtaking.

Adam, Eve, Lilith and The Stranger inhabit the Embattled Garden (1958). To a score by Carlos Surinach, it uses soaring, shimmering, climbable metal "trees" by Noguchi. Here, innocence seems to have vanished and partner swapping is the order of the day.

Night Journey (1947) has one of Noguchi’s ingenious sets in which the sculptured bed is modeled on the female pelvis and uses music by William Schuman. It centers on Jocasta, who inadvertently marries her son Oedipus after he solves the riddle which makes him King of Thebes. It starts with her about to hang herself, using the rope that the flashback turns into an umbilical cord. With its chorus of furies, this is perhaps the work that epitomizes Graham’s theatricality, technique and insight. Christine Dakin danced the leading role, as she did several others, with deep commitment and honesty.

Maple Leaf Rag, created six years before her death, reveals Graham’s humor, a trait not often associated with her. The program note reminded us that Louis Horst, her long time mentor and musical director, called her "mirthless Martha." At her request he would play Joplin’s music to cheer her up. This dance is partially a satire of herself and shows that it is possible to use her technique for something other than tragedy.

The legal battles that held up the performance of these works and the reopening of the Graham School centered around Ronald Protas, who first met and befriended Graham in 1967. In the 70’s, having held different positions in the School and the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance, he became executive director of the latter and a board member of both. He then went on to become Co-Associate Artistic Director of the Center and, after Graham’s death, Artistic Director of both. In her will she left him all her property not otherwise disposed of. Protas, with no training or background in the performing arts, claimed he owned exclusive rights to Graham’s name, which included all her works and the copyright on her technique. Almost all those who had studied and danced with Graham and had been teaching her technique and works were eventually dismissed and forbidden to do either. The Board of Trustees stepped in and Protas filed a lawsuit. The courts finally decided that Graham had given the Center the right to use her name as long as it existed and that she had sold the proprietorship of the School to the institution itself. All of the works created before 1956 were deemed to belong to the Center and the remaining ones created by her as an employee. Ten are in the public domain, five belong to the commissioning entities and the copyright renewal to one is held by Protas.

This whole, difficult drama has served as a lesson to choreographers to be clear regarding the rights to their works. The happy note is that, now, five decades of Graham dancers and teachers can share their heritage. The School and Center, in a newly constructed building on East 63rd Street, can now maintain the Graham legacy and archives, while encouraging new dancers and dance makers.

dawnlille@aol.com