Dance: Michel Platnik: Let us move through space

By Dawn Lille

ART TIMES Fall 2014

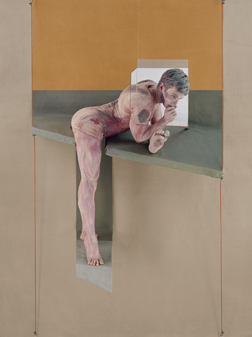

After Study for the Human Body (photo by Matan Ashkenazy) |

Usually I enter a gallery, walk through the first part of an exhibition to get a general impression, then go back and look at each work separately. When a friend took me to the Gordon Gallery in Tel Aviv to see the work of an emerging talent I continued this habit. But after a minute or two I realized something unusual was happening.

Enter the world of Michel Platnik, a French born artist who moved to Israel in 1998, graduated with honors from the Midrasha School of Art and received a prize for Excellence in Photography. Prior to this, due to his degree in electrical engineering, he had worked in the telecom field. But he also studied and practiced martial arts, performance art and the mime techniques of Etienne Decroix and Jacques Lecoq. He admired the theater of Ariane Mnouchkine and read extensively.

Platnik mixes painting, camera and video, via extensive use of the human body, to create “living paintings,” which, because of his attention to minute detail, allow the viewer to become part of an illusionary and interdisciplinary world. For several years he has been making works “after” Francis Bacon.

He uses models, often himself, to meticulously recreate or restage the scene of a Bacon painting. This is not really “appropriation” as the term is currently used; it could almost be called “homage and development.” Platnik does not attempt to duplicate or reconstruct the work, but, rather, uses it as a starting point. The first impression, that we are seeing some version of the original painting, is quickly dissipated and it becomes something else. If one were working only in dance it might be akin to using the famous Romantic print of the four ballerinas as the basis for a choreographic work (which has, in fact, been done).

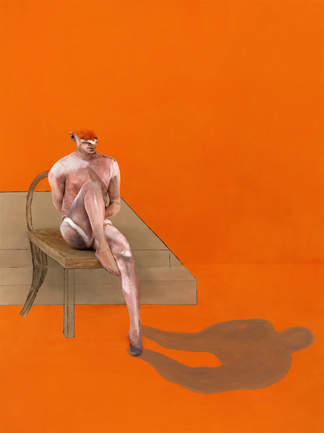

After Triptych 1983 right photo by Carolina Bonfil |

Each finished work is that of a team, which can consist of a model who has been carefully dressed and painted by makeup and costume designers, plus contributions by video and still photographers, a lighting designer and those who assist in the building and painting of the sets. Platnik conceives of, directs and is the artist who paints the body for each piece, which begins as a photograph.

Bacon portrays the torment of his objects via distortion. Platnik brings them to life and gives them the possibility of breaking out of the frame, of making a choice, of being more positive.

In After Three Studies for a Portrait of Lucian Freud, 1965 Platnik models the three faces on three screens. By the slow blinking of an eyelid or subtle inclination of the head, he constantly directs and redirects the viewer’s gaze. Seen in the very beginning of the exhibit, it was, in its sustainment, a sudden and almost frightening phenomenon.

In his painting Triptych, 1983, Bacon portrays three male figures, partially nude bodies clothed in briefs, with faces masked by blocks of color, plus their shadows. The two on either side are seated and the central figure is standing with his back to the viewer. The three videos imbedded in Platnik’s version are not synchronized. Thus to watch the entire performance is like watching simultaneously three scenes of a play, each performed on a different level, or to see a Merce Cunningham dance, where the audience is free to gaze on its choice of concurrent action.

After Triptych 1983 middle photo by Carolina Bonfil |

In the course of this work one can experience some of Platnik’s process. At different times and after various small gestures, movements and periods of stillness, each figure walks out, leaving his section blank. He then returns once or twice to paint the background (in speeded-up sequences), his shadow and the set. Just before the end (the entire piece lasts 34 minutes) the man on the right crosses his leg and the “picture” is again complete.

In After Study From the Human Body, 1991, the body of the solo male, obviously that of a trained dancer, is long, strong, sinewy and with beautifully articulated feet. The movement in the video often shows just the legs rising up to a full half toe position and then looking as they do when the body has risen straight up into the air in a jump. One hand is encased in a covering that makes it a foot.

The catalogue of the exhibit shares Platnik’s notes and sketches for this work in which he references the heroic male nudes of the Italian Renaissance and elements expressed in the Elgin marbles. The model here is Yamit Ardeni, a performer and choreographer with the Israel Ballet.

This piece really uses the human body as a guide to the exploration of time and space. Because of the model and his measured journey through his surroundings, we think we are seeing a dance.

After Triptych 1983 left photo by Carolina Bonfil |

Platnik’s process is the result of his life experience, plus his training as a photographer, in his manner of creating a tableaux and then going outside of the boundaries of painting. He uses time to force the viewer into perceiving the depths of the “painting” he has staged. When the movement increases, the observer has already been drawn into the pictorial entity and begins to explore and see, via the performance, the expanded space.

Martha Graham once said, “The body never lies.” In reality it is capable of even more expression than the face, where a person can often hide emotions. The structure of the face is what determines its expression, and since Platnik uses it as a dancer uses the body, he gets maximum expression from both in a painterly fashion.

Platnik’s use of the body as a tool or source, an object to be painted on and a guide to painting, makes him a remarkably original artist and a philosopher as well.

dawnlille@aol.com