Music: Organ Within: An Infinite Window

All photos: Enid Alvarez © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

By Christina Turczyn

arttimesjournal July 29, 2019

There is a park I visit near my home. Sometimes, I wait on a bench watching the stream rush by. At which point do those rivers reach the sea? How do you part water from water? Thought from breath?

At the same time, there is a need to walk as quickly as I can-to run. I am acutely aware that families are facing deportation. I feel an urgency to speak, to shake people up-to ask them how they continue to take the train to work when people all around us are being taken away, in darkness. Yes, here.

Tarek Atoui: Organ Within, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, June 27, 2019. Performer: C. Spencer Yeh. |

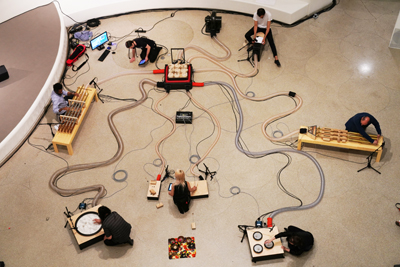

I had the great privilege, recently, of attending Tarek Atoui's Organ Within, a program of the Middle Eastern Circle Presents series at the Guggenheim, which included artists Chuck Bettis, C. Lavender, Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe, Victoria Shen, Keith Fullerton Whitman, and C. Spencer Yeh, introduced by Nat Trotman, Curator, Performance and Media. The ongoing series features the work of artists originating from, or based in the Middle East. I was stunned to see the organ de-contextualized, re-imagined.The collection of instruments, spread across the floor of the museum's Ronald O. Perelman Rotunda gave the organ, in the words of the composer, a new dimension of exposure. And what better venue for the performance than the widening spiral of the Guggenheim, which offers no real closure, but liberates? Looking onto the rotunda from where I stood, I thought that I might be looking into an infinite window from my vantage point, as into a Richard Diebenkorn painting, Blue Surround, perhaps. The music is accessible yet elusive-water moving over stone.

Tarek Atoui: Organ Within, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, June 27, 2019. Performers (clockwise from left): Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe, Chuck Bettis, Tarek Atoui, Keith Fullerton Whitman, C. Lavender, Victoria Shen, and C. Spencer Yeh. |

The opening of the piece resonated deeply with the urgency I feel, although I am sure that the reasons behind that are entirely different. Suddenly, I was standing inside a wind tunnel. The sound was like that of a plane rising, but I remained rooted where I was, since I wanted to know. I wanted to know why ropes of wind were weaving and unraveling, why one sound blended seamlessly into the next, and why there was a steady, premonitory beat. It was the rhythm that unsettled me-the ground beat, the suggestion of something happening beneath cobblestones, something that is insistent-something which we do not see. An ambulance? I had the same feeling while listening to the Un-drum, Strategies of Surviving, which might be one of the most powerful pieces I have ever heard. Is it a muffled march? Is it the sound of a lost word trying to keep itself alive? At times, that cadence became a very loud alarm. If it were light, it would be flashing a warning. The inchoate sound of a train that moved through the piece disappeared and returned.

One of the sound artists, C. Lavender, featured at the conversation which took place before the performance, observed that the hybrid sculptural object, the organ, was "essentially a family of instruments; they all work together, but they're also individuals. So it started by sort of learning each one as an individual, exploring it, exploring its tonal palette, seeing where it can go…" The artists prefer to think of this as a collaborative piece in the process of creation. With strong improvisational backgrounds, this was the first time that they had performed a new interpretation of Within together. Tarek Atoui wanted to create "an instrument that could be played and felt by hearing and deaf persons at the same time." Focus on the physical and spatial nature of sound emerged strongly, and in my opinion, the notion of tactile sound will revolutionize the way we learn. Now, students of music, as well as countless others, can imagine with their sense of touch, at the very least.

Tarek Atoui: Organ Within, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, June 27, 2019. Performer: Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe. |

Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe added that the synthesizer "that [he] built that lived in the back of-the back gallery, was meant to be a mirror or an echo of an organ where you have this sort of microcosm of the world that was creating a generative patch…" in effect summoning music echoing music. We don't often think of the internet as a site where words echo words infinitely, yet current technology creates a mirror. Atoui has often commented upon making instruments that create their own sounds. Recalling the Reverse Collection/Reverse Sessions, Lowe told the audience that objects were built through the "reverse engineering" of a sound. In the past, while describing the ways in which he put himself in "a situation of total improvisation,"Atoui talked about how an instrument reconsiders itself. I like the idea of art reconsidering itself-for example. a painting that has survived the centuries, always breathing a different air-or a found poem, found object.

What fascinates me about Atoui's compositions with electro-acoustic or other instruments is the potential that they contain for revolutionizing the idea of hearing. I hear through the bone-tactile sound is vital. Some of Atoui's work occurs in frequencies that most of us cannot hear, a phenomenon which must take us outside of the familiar. This aspect of his work alone might ask us to experience the world differently. To see a painting is one thing-to pass your hands along the textural surface of a Van Gogh is another. What tides of sound does sculpture contain? Sound erases the borders between subject and object, communicating without tense.

This was the first time that Organ Within was rendered by hearing artists, solely. In the past, the piece had been performed by deaf musicians. Atoui spoke to the relationship between sound and deafness, one which has emerged in so much of his work, affirming that "deafness is an expertise, rather than a handicap." He felt, as well, that learning from the deaf community was critical. In the past, Atoui worked intensely with the Al Amal School for the Deaf.

Tarek Atoui: Organ Within, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, June 27, 2019. Performer: Victoria Shen. |

Before the performance, Atoui mentioned that listeners would hear sounds from all directions. The physical nature of sound emerged in the discussion, again and again. I found myself turning to the right or left to look for a sound after it had disappeared, as though it were phantom, delimiting space. Victoria Shen's work is described by the Guggenheim as "music [that] floods its location, acting as a form of sculpture." "Sign language," Atoui added, "is very visual," and this is sound sculpture that integrates music and art. And we do not often think about the sound that sculpture releases. In Unplified, which is a piece in dialogue with the novel Men in the Sun, by Ghassan Kanafani, sounds of the desert of Ash Sigaya stream through a microphone. The idea of sound, heard and unheard, freed by the environment, opens up artistic boundaries.

The Organ Within asks one to think deeply about music. To consider what listening might be. What is it like to hold sound, water cupped in your hands? To wash yourself in its atoms? What is it like to walk through sound? To cry out? The idea of tactile sound in education is revolutionary. As an educator, I have always loved Paulo Freire's belief that we learn through the body. I believe that we are constantly absorbing through all means-people receive information in diverse ways. It is the social context, only, that limits the means, creating a hierarchy of perception.

Tarek Atoui: Organ Within, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, June 27, 2019. Performers (from left to right): Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe, Chuck Bettis, C. Spencer Yeh, C. Lavender, Tarek Atoui, Victoria Shen, and Keith Fullerton Whitman. |

Atoui's Organ Within expressed incredible emotional force, drawing us in. It is a provocative and timely work, in which a red, heart-like instrument beats for the organ, while weights are added and subtracted to control the flow of air. "And the heart does not die/when one thinks it should," I thought, reminded of Czeslaw Milosz, remembering survival. I thought of Fahrenheit 451. I remembered, also, Lucille Clifton's writing "for the blind." " You will stand in a room/where you have never lingered/you will touch glass/someone will face you with bones/repeating your bones/you will feel them in the glass/your fingers will shine." The end of the Atoui's piece is especially alive and strong. People were dancing.

Once, I taught at a university where we were told that a mother walked her daughter to school daily, until, in that brutally cold climate, she could no longer walk, because she did not own a sweater or a coat. There was a call for coats, yet I cannot forget that call. I imagine someone walking through the cold, moving her daughter closer to a place of understanding. I think that Tarek Atoui moves people with disabilities towards this place, away from silence. We all move toward voice. Often, the difference between life and death in current times is voice.

I think about the ways in which artists in education can cross boundaries. I think about where they can teach. I consider the work they have done in places where others could not follow. I think of this work in the light of its accessibility and power. Work at the cutting edge will be interdiscliplinary-I can no longer imagine specific fields at universities that close in on themselves. That I, with a rare hearing disorder, can write about this piece, is new.