Speak Out: Judy Chicago and The Dinner Party

By Amy Weber

arttimesjournal November 21, 2019

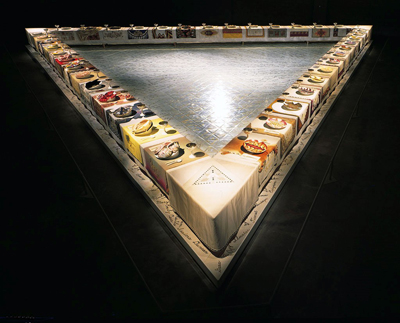

Judy Chicago, "The Dinner Party", 1979, mixed media, 48x48x48 feet, courtesdy, Brooklyn Museum Judy Chicago, "The Dinner Party", 1979, mixed media, 48x48x48 feet, courtesdy, Brooklyn Museum |

Judy Chicago, best known as a pioneer in the feminist art movement of the 1970s, is no stranger to gender bias. In 1974, Chicago created her most well-known work, The Dinner Party. This work is in the shape of a triangle, a symbol of femininity as well as of equality and includes the names and information for over 1,000 women who impacted Western civilization. The massive (in endeavor as well as in scale) The Dinner Party prompted varied opinions, from highly supportive to deeply critical.

Says Maura Reilly, Founding Curator of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, "Some critics praised the work's socio-political content; others attacked the 'central core' images as literal vaginas rather than metaphoric celebrations of female power." In 1990, members of Congress agreed with the critics Reilly describes by deeming the piece "pornographic" and "offensive" and disallowed installation of the piece at the University of the District of Columbia.

While the number of female artists is slowly increasing in representation at fairs, exhibitions, and shows, Chicago's struggle for place and against long-entrenched biases against female artists continues into this decade, as she fights to establish her legacy in a foundation, gallery space, and center for feminist art in her adopted home of Belen, New Mexico.

In 1996, Chicago moved to the small town in rural New Mexico, where locals oppose her attempts at opening an arts center, calling her artwork, again, "inappropriate" and "pornographic." Belen's downtown is full of empty buildings, and most of its young people have had to leave for education and jobs. About 25% of the population live below the poverty line. In other words, Belen is a struggling community, and, despite the tourism dollars that a major arts center would attract and the artists and museum, foundation, and gallery workers that could provide a much needed influx of population, not to mention the prestige of having a major center of feminist art in this small, remote town, community members still fight against Chicago's plans. The community's discomfort with feminist motifs seems to outweigh its desires to revitalize an impoverished place.

In an echo of The Dinner Party's rejection from the University of the District of Columbia, the backlash in Belen resulted in the town refusing a grant of $13,000 for Chicago's gallery and research library, the proceeds of which would all go back to the town of Belen, becoming a small, but much-needed revenue source. Instead, Chicago raised $80,000 on her own and finally opened the space this year. This victory has resulted in the opening of another 6 galleries in what is now deemed Belen's Art District, to the great joy of Mayor Jerah Cordova, who believes that these artists and new businesses will be integral to Belen's downtown revitalization. "Our downtown was hit pretty hard," Cordova said. "It's hard to fill those buildings sometimes, there's a lot of vacancies. What we hope is that the art can revitalize downtown, bring business back."

Chicago's story is one of ongoing battles against prejudice. Her undying dedication to asserting herself and her work into the cultural lexicon has led to some eventual victories. Despite all of her many achievements, her successes as a professional artist, and even her fame, she still cannot take for granted she will be taken seriously as an artist. Despite 40+ years of gains in women's equality, Chicago encounters similar pushback and rejection as she did in the beginning of her long career. Although her center for feminist art in New Mexico may not be as great as she envisioned, and it may take longer to establish than she expected, if history is any indication, she will eventually overcome.

Amy Weber lives in Santa Fe, NM, is a junior at the Savannah College of Art

and Design, while also working as a Visual Communications Consultant.